Tailoring Cancer Prevention Strategies to Different Populations

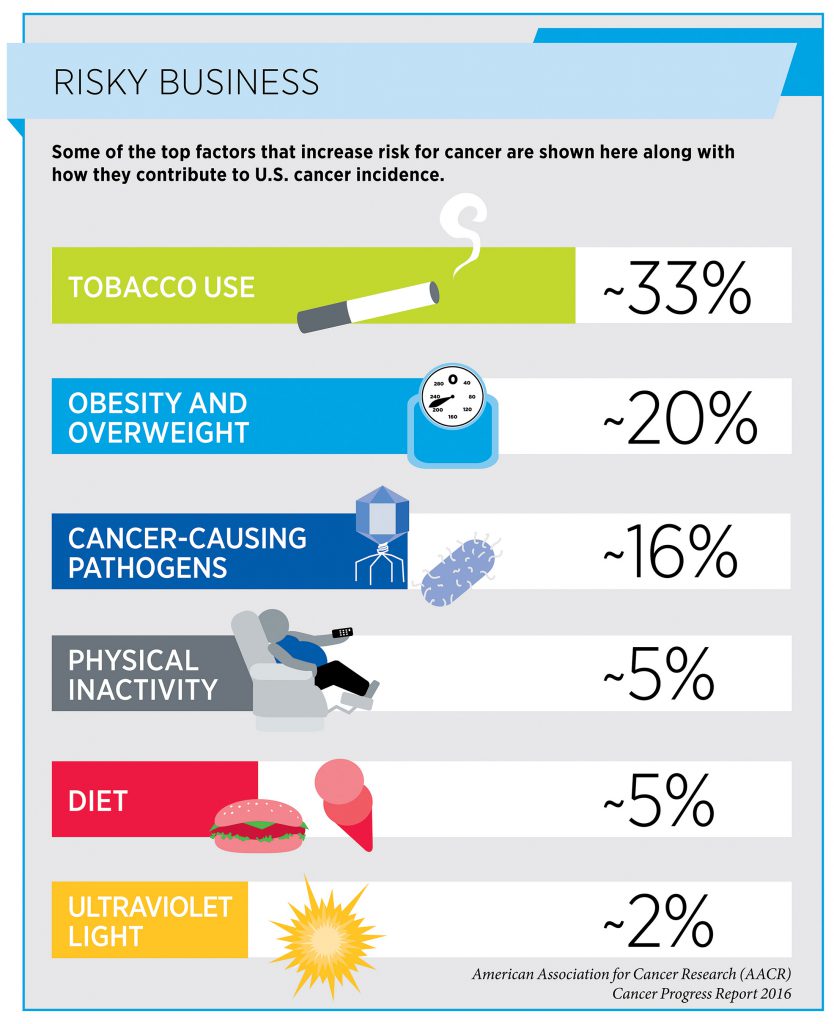

Did you know that you can reduce your risk of developing certain types of cancer by reducing or eliminating your exposure to particular factors in the environment? Among these factors are tobacco products, alcohol, and cancer-associated pathogens like human papillomavirus (HPV).

Understanding the identity of the factors that increase risk for a particular type of cancer is vital for developing and implementing effective clinical and public health initiatives to reduce incidence and mortality of that type of cancer.

For example, after it became widely known in the mid-1960s that cigarette smoking could cause lung cancer, the U.S. government enacted numerous measures to reduce smoking prevalence and to limit exposure of both smokers and nonsmokers to cigarette smoke. The measures, including increased taxes, increased public education, and increased regulation, have driven down smoking rates among U.S. adults from 42 percent in 1965 to 15 percent in 2015. This has led to a decline in the U.S. lung cancer incidence rate and has been credited with preventing almost 800,000 deaths from lung cancer from 1975 to 2000.

In some cases, however, multiple factors increase risk for a particular cancer type. The results of a paper published recently in the AACR journal Cancer Research by a team of researchers led by Terry M. Jones, MD, professor of head and neck surgery in the Department of Molecular and Clinical Cancer Medicine at the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom, highlight the importance of not generalizing the relative contributions of distinct factors to cancer risk in different populations. This is important because it indicates that reducing the burden of a particular cancer in different populations may require distinct combinations of disease prevention strategies.

Role of HPV in Driving Rise in Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence

Oropharyngeal cancer is a type of head and neck cancer. It includes cancers arising in the tonsil, base of the tongue, soft palate, and the side and back walls of the throat. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is the most common form of oropharyngeal cancer.

Terry M. Jones, MD, professor of head and neck surgery in the Department of Molecular and Clinical Cancer Medicine at the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

The three main factors that increase a person’s risk for OPSCC are cigarette smoking, being infected with certain types of HPV, and heavy alcohol use. Exposure to each of these factors can be reduced or eliminated in different ways. Understanding the relative contributions of these factors to the burden of OPSCC in different populations is vital for ensuring that disease prevention strategies are tailored to the individual populations.

“Incidence of OPSCC has been increasing throughout the developed world since the mid-to-late 1990s,” said Jones in a news release. “Several studies suggest that this rise was driven by increasing incidence of HPV-positive disease, but we wanted to determine whether this was the case across all four countries of the U.K.”

To do this, Jones and a large multidisciplinary team of colleagues from many of the major head and neck cancer centers in the U.K. determined the HPV status of archival tumor tissue from 1,602 patients who had been diagnosed with OPSCC from 2002 to 2011. Each sample was analyzed using three validated commercial tests for HPV.

Valid results from each of the three tests were obtained for samples from 1,474 patients. The prevalence of HPV infection among these patients overall was 51.8 percent. When the patient samples were considered by the year of disease diagnosis, the proportion of samples testing positive for HPV did not vary significantly between years, remaining static at about 50 percent.

“We were surprised to find that while the overall incidence of OPSCC in the U.K. rose year on year as anticipated, the proportion attributable to HPV remained static, meaning that not only is HPV-positive OPSCC increasing in incidence, but that HPV-negative OPSCC disease incidence is rising in parallel,” said Jones. “This is different to trends reported elsewhere in the developed world, which illustrates that we cannot generalize the causes underlying the rise in OPSCC incidence between populations; they must be analyzed in a population-specific manner.”

The NCI states that in the United States, estimates of the incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers increased by 225 percent from 1988 to 2004, while the incidence of HPV-negative cancers declined by 50 percent.

“The magnitude of the increase in incidence of HPV-positive OPSCC in the United States and the United Kingdom over the past few decades is indeed very similar,” said Jones. “The striking difference in our findings was that the incidence of HPV-negative disease also rose during the study period, while it has been reported to have declined in the United States. These results suggest that exposures to risk factors for HPV-negative disease may vary markedly between the two countries.”

Jones noted that the team’s hypothesis is that alcohol consumption is driving the increase in HPV-negative disease in the United Kingdom, but that they do not have clear evidence for this as yet. He also explained that the U.K. data pertaining to HPV-positive disease provides further evidence in support of a gender-neutral HPV vaccination policy in the United Kingdom.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also has gender-neutral recommendations for childhood vaccination with any of the three vaccines approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for preventing infection with most of the cancer-associated types of HPV. Specifically, the CDC recommends HPV vaccination for girls and boys at age 11 or 12.

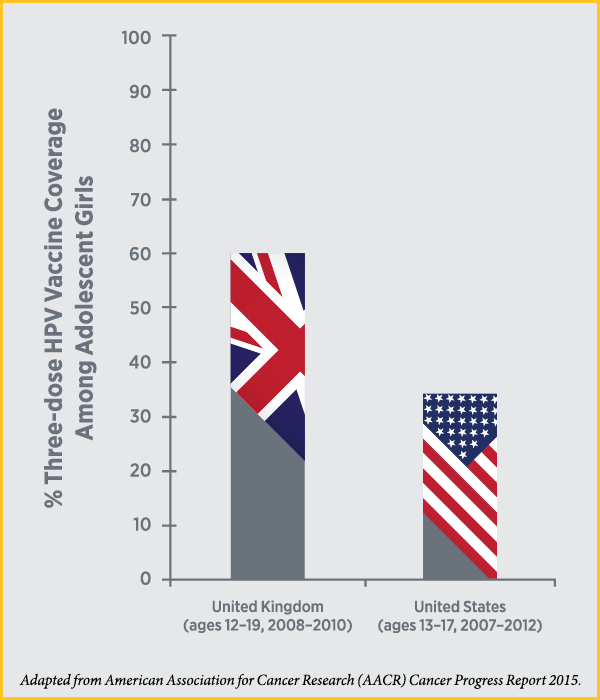

However, the percentage of adolescent girls in the United States to have received the recommended three doses of an HPV vaccine is very low compared with the percentages vaccinated in other high-income countries, such as the United Kingdom. Although the percentages are creeping up slowly in the United States, the CDC estimates that as of 2015, only 42 percent of girls and 28 percent of boys ages 13 to 17 had completed the three-dose HPV vaccine series.

It is estimated that in the United States, more than 50,000 cases of cancer, including thousands of cases of oropharyngeal cancer, could be prevented if 80 percent of those for whom vaccination is recommended were to be vaccinated. As a result, many researchers are actively investigating how we can increase HPV-vaccine uptake in the United States. Some of the most recent research in this area is highlighted in another post on this blog.