Cancer “Big Data” Buzz in San Francisco

When the hottest minds in cancer genomics meet the hottest minds in computational and systems biology, you can rest assured that effective integration of big data into cancer clinics is on the horizon. Yes, that’s what is happening in San Francisco next week: The AACR is hosting two special conferences—Translation of the Cancer Genome, held Feb. 7-9, and Computational and Systems Biology of Cancer, held Feb. 8-11—for experts in these two overlapping and rapidly evolving fields to find new opportunities for transdisciplinary collaborations.

I spoke with William C. Hahn, MD, PhD, co-chair of the Translation of the Cancer Genome conference, and Andrea Califano, PhD, co-chair of the Computational and Systems Biology of Cancer conference, for a sneak peek at the exciting events happening at the two meetings.

Translation of the Cancer Genome

William C. Hahn, MD, PhD, speaks at the 2013 AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Boston.

“Decoding the cancer genome is an essential first step in allowing us to understand cancer and the causes of cancer. The Translation of the Cancer Genome conference is about how you take that large amount of information and translate it into meaningful outcomes for patients,” said Hahn.

Hahn, who is an associate professor in the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Cancer Genome Discovery at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said the meeting will showcase exciting discussions on systematic approaches to identifying new targets and pathways in cancer, new ways of using genome technologies to diagnose cancers, and new methods to use the latest information to facilitate cancer drug discovery.

Computational and Systems Biology of Cancer

Andrea Califano, PhD, speaks during a plenary session at the AACR Annual Meeting 2011 in Orlando, Florida.

“There has been a dramatic revolution in the way we approach biological problems: It has gone from being essentially an empirical, “trial and error”-based process with hypotheses formulated based on accumulating evidence to being a more data-centric and model-based discovery process,” said Califano. The complexity of biology requires novel paradigms for looking at the data, both from a genomic perspective and from a computational analysis perspective, and that is precisely what the Computational and Systems Biology of Cancer conference has to offer, said Califano, who is a professor in and chair of the department of systems biology, director of the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center, and associate director of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University.

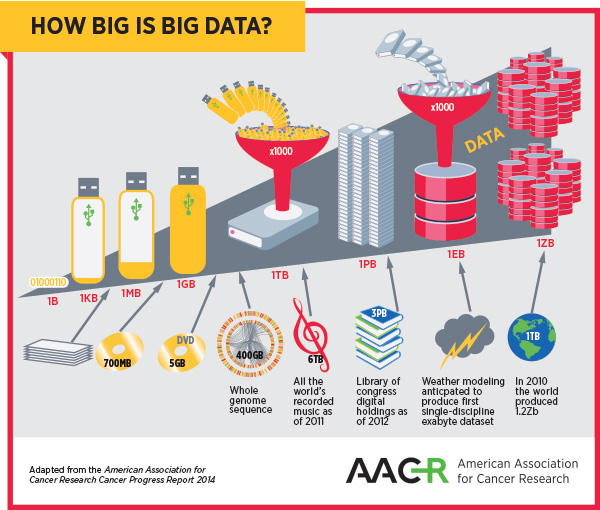

The first part of the conference deals with the large volumes of cancer data—how we organize it, how we think about getting additional information out of it, and what kind of problems we have to tackle with this type of information. The second part of the conference is dedicated to the revolution that is happening in biology, which is a shift from a more statistical view of data analysis to a more model-driven one, Califano explained.

A Day of Combined Sessions

A highlight of the two conferences is a day of combined sessions, where researchers from each of the conferences will share and discuss their data on topics including biomarker and genomic approaches to patient stratification, clinical applications of big data, and the scope of network-based cancer biology.

As the complexity of cancer and its treatment create big datasets, the field and the patients it serves will benefit greatly from optimizing methods of storing, accessing, and analyzing big data.

“We have two main camps here, one camp that is working on data analysis using statistical approaches and the other camp that uses model-based or network-based approaches. There is a lot of space that is common for these two communities,” said Califano. “So, we are organizing a set of combined sessions where this overlap is explored and the potential synergies and shared methodologies are presented contextually.”

One study, for example, will discuss generation of a chemical-genetic interaction map that can measure the influence of aberrant cancer genes on drug responses. Another study will discuss identifying low allele frequency mutations using deep sequencing, many of which are likely cancer drivers with potential functional and/or clinical importance, and most of which may not be identifiable using standard sequencing depths.

“Experts in these two fields need each other,” said Hahn. “As we generate exhaustive information on cancer genomes and learn how heterogeneous cancers are, the idea of creating computationally rigorous ways of looking at these data and making sense of them has become a priority.”

In the coming years, researchers from both fields will take all the evidence they get from cancer genetics and from modeling to understand the complexities of cancer and develop a unifying principle and an organized approach to predictive medicine that can take personalized oncology to the next level, said Califano.