News from the Cancer Centers: How DCIS Becomes Invasive Breast Cancer

Earlier this year, a study published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), explored the question of how preinvasive breast tumors become invasive. The study’s lead author, Kornelia Polyak, MD, PhD, discussed the findings in an article published by Inside the Institute, a publication of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Polyak, who was the program committee chair for the AACR Annual Meeting 2017, identified CD8+ T cells, also known as killer T cells, as a potential way for physicians to predict which cases of ductal carcinoma in situ will progress to invasive breast cancers. Cancer Research Catalyst thanks Dana-Farber for allowing us to republish the article.

Study shows breast cancer and immune cells co-evolving

Like fugitives who become ever more canny about eluding their pursuers, tumors shift their molecular tactics over time to avoid an immune system attack. The immune system, meanwhile, makes its own adjustments, gearing its response to the changing face of its foe.

This contest of move and countermove isn’t a sign of cunning or ingenuity on cancer’s part, but of evolution in action. As the cancer cells most vulnerable to an encounter with the immune system die off, the hardier cells within a tumor begin to predominate. If the immune system doesn’t respond effectively, the tumor may continue to grow and, eventually, metastasize.

In a new study, researchers at Dana-Farber tracked how cancer cells and immune system cells co-evolve as preinvasive breast tumors become invasive. The results, published in the journal Cancer Discovery, have the potential to influence breast cancer treatment at all stages of the disease. In the early stages, knowing the precise mix of immune cells within breast tissue may help doctors determine which preinvasive tumors are likely to turn invasive. For more advanced cancers, the mix may indicate which immunotherapies are most likely to be effective.

The general thrust of the researchers’ findings is that as breast tissue makes the transition from a preinvasive to an invasive state, the immune system cells in its vicinity – or “microenvironment” – become less active against the cancer cells. The discovery helps explain how tumors dodge an attack from the immune system as they develop. The researchers also uncovered some of the molecular machinery in both cancer and immune system cells that allows the process to take place.

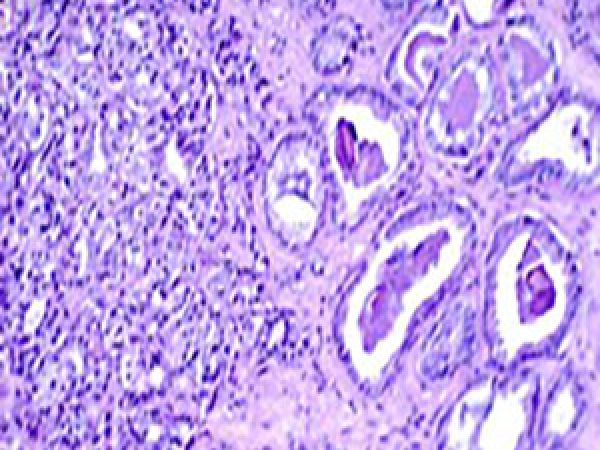

“Tumor tissue is often a composite of cancer cells and the immune system white blood cells. However, in early stages of tumor development, these cell types are separated by the walls of the milk ducts, and only when the tumor becomes invasive do they intermingle with each other,” says Dana-Farber’s Kornelia Polyak, MD, PhD, the study’s senior author. “In fact some tumors contain more white blood cells than tumor cells. In this study, we wanted to explore how both sets of cells change from preinvasive tissue to invasive disease and the effect of those changes on the immune response to cancer.”

The diversity within tumors goes beyond the cancer cell/immune system cell dichotomy. Both the cancer cells and white blood cells appear in a variety of subtypes, each with distinctive genomic features. In the case of the white blood cells, these differences affect the intensity and duration of their attack on cancer.

The study used tissue from women with either triple-negative breast cancer (which lacks receptors for estrogen, progesterone, or the protein HER2) or HER2-positive breast cancer (which tests positive for the HER2 receptor). To trace the evolution of these cancers, researchers analyzed the assortment of white blood cells in normal breast tissue, in ductal carcinoma in situ (or DCIS, a preinvasive condition), and in invasive ductal cancers of the breast. They focused particularly on T cells, white blood cells that help lead the charge against cancer.

Among their findings:

- DCIS tissue contained large numbers of CD8+ T cells (also called killer T cells) that are active against tumor cells, but invasive tumors contained fewer;

- The number of T cell subtypes – a measure of the flexibility of T cells’ response to cancer – was higher in DCIS than in invasive tumors;

- DCIS cells carried only trace amounts of PD-L1 – a checkpoint-inhibitor protein that dampens a T cell attack – while invasive tumors carried much more.

These findings depict a drop in anti-cancer immune activity as DCIS morphs into invasive ductal cancer. “The DCIS-to-invasive breast cancer transition appears to be the most critical step in the process of tumor progression, both from a clinical and immune system point of view,” Polyak notes.

“Currently, there are no reliable tests for determining which patients with DCIS have the greatest risk of developing invasive cancer,” she continues. “Our data suggest that the frequency of activated CD8+ T cells may help doctors predict which DCIS is likely to progress, so patients can receive appropriate treatment.”

Dana-Farber contributors to the study include: Carlos R. Gil Del Alcazar, PhD, the paper’s first author; Sung Jin Huh, PhD; Muhammad Ekram, PhD; Anne Trinh, PhD; Lin Liu; Francisco Beca, PhD; Ying Su, MD, PhD; Lina Ding, PhD; Gordon Freeman, PhD; Judy Garber, MD, MPH; and Franziska Michor, PhD.