AACR’s Inaugural Pediatric Cancer Progress Report Highlights Decades of Advances, Powerful Survivor Stories, and Urgent Unmet Needs

Kaley Ihlenfeldt was 8 when she was diagnosed with diffuse midline glioma (DMG), an aggressive type of pediatric brain cancer with a survival rate of only 4%. Her parents were told she had nine to 18 months to live.

“How do you tell that to your kid? She’s 8. She wants rainbows and butterflies and unicorns and to play with her sister,” explained Jenny, Kaley’s mother. “As parents, that’s not an acceptable answer.”

In looking for another answer, her parents found a clinical trial for a first-of-its-kind drug designed to target tumors with a H3K27M genetic mutation—the same alteration driving Kaley’s cancer. After getting into the trial, her family drove six hours every few weeks from their home in Wisconsin to the clinical trial site in Michigan through harsh winter conditions and grueling Chicago traffic so Kaley could get the treatment.

Five years later, she continues to take what is now known as dordaviprone (Modeyso), which “has kept this demon at bay for us,” Jenny said. Now 14, Kaley is enjoying her freshman year of high school and getting to perform in drama club, play softball, and just hang out with her friends and family.

“If you saw her on the street, you would think there is absolutely nothing wrong with this kid, and she got diagnosed with one of the most deadly brain cancers out there,” Jenny said.

Thanks to research breakthroughs, dordaviprone became the first-ever therapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for recurrent DMG in August 2025.

Kaley’s story is just one example of the progress that has been made in pediatric cancer over the last decade. Between 2015 and 2025, the FDA has approved 36 new treatments for children and adolescents with cancer. To highlight the impact of these advances and put a spotlight on the gaps that still exist in treating pediatric cancer, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has published its inaugural AACR Pediatric Cancer Progress Report.

“The first AACR Pediatric Cancer Progress Report is a celebration of the incredible progress in treating children and adolescents with cancer coupled with a call to action toward a brighter tomorrow,” said Kimberly Stegmaier, MD, cochair of the report’s steering committee and chair of the Department of Pediatric Oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “As a pediatric oncologist and physician scientist, I have witnessed firsthand this transformation in care for some pediatric patients with cancer but also the heartbreak when our treatments fail. Research brings a new future for these vulnerable children, adolescents, and their families.”

The Progress Made Against Pediatric Cancers

Pediatric cancers, defined as cancers in children (ages 0 to 14) and adolescents (ages 15 to 19), are collectively considered to be rare, and the number of cases diagnosed each year is on the decline, according to the AACR Pediatric Cancer Progress Report 2025. Between 2015 and 2022, the overall incidence rates of pediatric cancers have dropped 1% each year. It is estimated that in 2025, around 15,000 children and adolescents will be diagnosed with cancer in the United States.

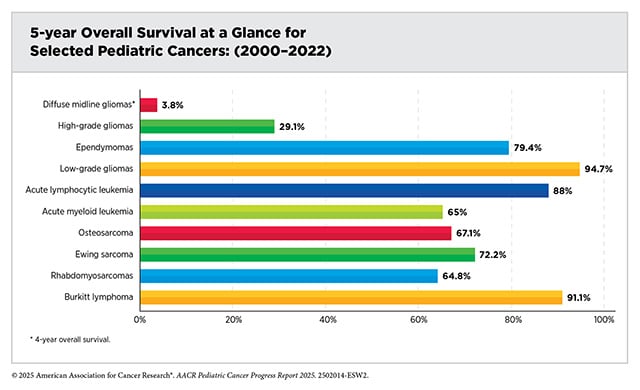

But the report found that incidence rates have varied by pediatric cancer type. For example, the global incidence of thyroid cancer increased 1.17% each year between 1990 and 2021. The report detailed a similar variance in survival from pediatric cancers. For all pediatric cancers combined, the five-year survival rate in the United States increased from 63% in the mid-1970s to 87% in 2015-2021. However, while Hodgkin lymphoma, thyroid carcinoma, and retinoblastoma have five-year survival rates exceeding 90%, the rates are below 25% for other cancers, like certain gliomas and sarcomas.

“The report elucidates how innovative research, often funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has improved outcomes for many of our youngest cancer patients,” explained Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, FAACR, cochair of the report’s steering committee, an AACR Past President, and co-executive director of the Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “We also document that in several lethal cancer types, there remains a significant need for new insights, novel therapies, and international clinical trials to achieve similar progress.”

Among the progress that has been made, the report examines advances in both immune-based therapies as well as more targeted, personalized therapies that are the result of new insights into the unique biological underpinnings of pediatric cancer.

For example, researchers found that alterations in the KMT2A or NPM1 genes can lead to more aggressive acute leukemias. Since these mutations depend on the protein menin to promote the development of leukemia, researchers tested whether inhibiting menin could effectively treat leukemia. In November 2024, revumenib (Revuforj) became the first menin inhibitor approved for adult and pediatric patients with acute leukemia harboring a KMT2A mutation.

It was also the only option left for 14-year-old Tyler Peryea when he joined a trial examining revumenib in patients with acute myeloid leukemia that harbored a NPM1 mutation. It helped drop his leukemia cells low enough to undergo a second stem cell transplant, and is “doing amazing,” according to his mother, Jamie. Now 15, Taylor is continuing to take revumenib to prevent relapse, but his focus is back on his schoolwork, playing games with his friends, and fulfilling his dream of becoming an actor.

“Clinical trials gave Tyler his future,” Jamie said.

Clinical trials also led the FDA to approve revumenib for another indication in October 2025: the treatment of adults and pediatric patients for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with a NPM1 mutation.

Addressing the Gaps in Pediatric Cancer

However, the AACR Pediatric Cancer Progress Report 2025 indicates that progress has slowed down in recent years as survival rates only increased 0.5% per year since 2000 in the United States where an estimated 1,700 children and adolescents are expected to die from cancer in 2025.

Further, there are significant disparities in those who develop and die from pediatric cancer in this country. The highest incidence rates are seen among Hispanic children, while non-Hispanic Black children are nearly 30% more likely to die from certain pediatric cancers compared with non-Hispanic white children.

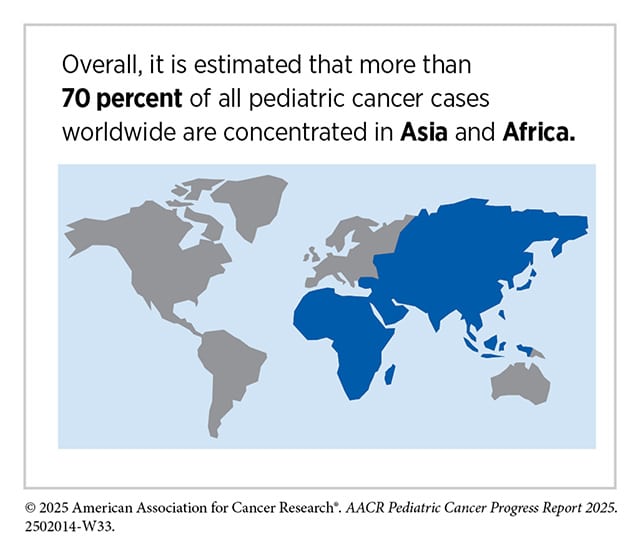

The disparities are even more stark on a global scale. Each year, about 400,000 children are diagnosed with cancer worldwide, but 80% to 90% of cases occur in low- and middle-income countries. Due to a lack of resources, underdiagnosis, and delays in care, survival rates can vary greatly between low- and high-incomes countries. For example, retinoblastoma, an aggressive eye tumor, has a survival rate as high as 98% in some high-incomes countries compared with 57% in low-income countries.

That is why, among the actions recommended in the report, there is a call to foster more global and public-private partnerships by streamlining data-sharing capabilities through federated databases and establishing regulatory processes to facilitate more clinical trials around the world. Among the efforts the report points to as examples are the international Pediatric Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (MATCH) trial involving around 200 children’s hospitals, university medical centers, and cancer centers in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, as well as the multiarm adaptive interventional platform AcSé-ESMART trial that has so far enrolled more than 250 patients from six countries across Europe.

The report also calls for policy changes to help expand access to pediatric cancer clinical trials within the United States, such as, for example, offering tax credits or extended market exclusivity to encourage industry to increase their investment in pediatric cancer research and hence the number of available clinical trials. Other policy recommendations include establishing Medicare reimbursement models to help support those who can’t afford to participate in trials and the increased use of decentralized trials to make them more accessible for those unable to travel.

And of course, none of the progress already made would have been possible without funding for research. So, the AACR Pediatric Cancer Progress Report 2025 recommends that Congress provide at least $51.303 billion for the NIH and $7.934 billion for the National Cancer Institute in fiscal year 2026, while also supporting other federal agencies and programs that focus on pediatric cancer research and patient care.

“There’s not enough funding for pediatric cancer, and that has to change,” implored Jamie Peryea, who knows from experience how research can save the life of a child with cancer. “Every child deserves a chance.”