Can Some Breast Cancer Patients Skip MRI or Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy?

The multitude of treatments that cancer patients undergo is often a blur—appointments, scans, acronyms—and a drumbeat of decisions that feel too big for the time one has to make them. In that swirl, the idea that some steps might safely be skipped sounds almost implausible. Yet at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2025, investigators brought forward trial results and data that ask a straight question: When can less be enough, and when does “more” seem no longer suitable to move the needle? Their answers came not as sweeping pronouncements but as measured findings, bounded by study design, patient populations, and the limits of follow-up.

“We are encountering increasingly complex multidisciplinary treatment decisions where we are trying to balance our local therapies—surgery and radiation—with systemic therapy to right-size care for our patients with breast cancer,” said Tari A. King, MD, professor and chief of the Division of Breast Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Emory University School of Medicine, and moderator of the “Clinical Controversies: Management of the Axilla in Multidisciplinary Care” session at SABCS.

This concept of pushing towards de-escalation isn’t new. “We take SLNB [sentinel lymph node biopsy] for granted in 2025, but in 1991, I was convinced it would not work—when it did start to work, I asked the question—can sentinel node biopsy alone achieve axillary control, that is, do you have to do an axillary node dissection?” said Armando E. Giuliano, MD, the SABCS William L. McGuire Memorial Lecture Awardee and chair in surgical oncology at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Giuliano was a pioneer who brought SLNB into breast cancer surgery to stage the axilla with fewer complications than routine axillary lymph node dissection. A field of inquiry that was taken a step further by Marjolein Smidt, MD, PhD, professor at the Maastricht University Medical Center in the Netherlands, who presented data on the BOOG 2013-08 phase III clinical trial where sentinel lymph node biopsy was omitted in a defined group of patients with early-stage disease.

De-escalation in the Axilla: Clinical Trial Evidence for Skipping SLNB

“Over the past two decades, breast cancer care has shifted toward minimizing invasiveness while preserving oncologic safety,” said Smidt, in a press release. She described SLNB as the preferred axillary staging approach for early-stage disease, and noted that in patients whose lymph nodes are clinically negative, accumulating evidence indicates SLNB is primarily prognostic and seldom changes systemic treatment decisions. SLNB is a procedure in which the lymph node that is the first to take up a dye or radioactive substance when injected near the tumor (the sentinel node) is identified, surgically removed, and examined.

“In addition to the potential scarring and discomfort of having some lymph nodes surgically removed, patients undergoing SLNB also run the risk of experiencing long-term side effects like lymphedema, which is swelling caused by the build-up of lymph fluid, often requiring physiotherapy,” said Smidt, further explaining the need to ascertain whether omitting SLNB in clinically node-negative patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy could be safe under contemporary conditions.

Smidt and colleagues enrolled 1,733 patients with early-stage disease; the tumors were up to 5 cm and lymph nodes were deemed clear based on physical examination, preoperative ultrasound, and tissue analysis when indicated. All underwent breast-conserving surgery and radiation at 25 hospitals in the Netherlands between 2015 and 2022, then were randomized to SLNB or omission of SLNB.

With a median five-year follow-up across 1,574 evaluable patients—749 in the SLNB arm and the remainder in the omission arm—the authors reported regional nodal recurrences of 0.5% in the SLNB group versus 1.2% in the omission group, a difference they described as not statistically significant. They further reported median five-year regional recurrence-free survival of 96.6% in the SLNB arm versus 94.2% in the omission arm, again without a significant difference between groups. Smidt summarized that the study suggests SLNB may be safely omitted in certain patients with early-stage hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative disease, noting that 86.6% of tumors in the trial were of this subtype.

Smidt emphasized the need for careful follow-up because of the well-known potential for late recurrences in HR-positive disease. She also commented on possible procedural benefits of avoiding SLNB, including cost-effectiveness, shorter treatment times, fewer complications, and smoother recovery, while outlining limitations such as incomplete five-year follow-up and reliance on per-protocol analysis. She drew attention to evolving radiation practices—from whole-breast irradiation, which was standard at trial initiation, to protocols such as partial-breast irradiation—and said the trial cannot prove the safety of SLNB omission under those newer protocols, though extrapolation may be considered in future analyses. She stressed that the results most strongly apply to HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors 2 cm or smaller, since larger tumors and other subtypes were underrepresented.

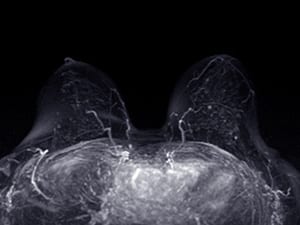

The MRI Question: Seeing More vs. Doing Better

In a different clinical space—diagnostic imaging before surgery—Isabelle Bedrosian, MD, a surgical oncologist and professor of breast surgical oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, led a randomized phase III trial that investigated what impact preoperative breast MRI has for patients with stage 1 or 2 HR-negative breast cancer who are eligible for lumpectomy. Bedrosian explained that MRI is commonly included because it can detect disease not seen on mammography, but MRI often leads to additional testing, surgical delays, and increased financial burden.

She noted that those costs and delays would merit acceptance if MRI were linked to better outcomes but emphasized that its impact on such outcomes has been understudied. Bedrosian and colleagues designed the Alliance A011104/ACRIN 6694 clinical trial to test whether detecting and removing mammographically occult disease by MRI reduces local recurrence and improves locoregional control.

The study enrolled 319 patients who did not have an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation, did not have cancer in both breasts at the same time, and had no history of prior breast cancer. All had diagnostic mammography with or without ultrasound, then were randomized to receive or forego additional imaging by MRI. After a median follow-up of 61.1 months, 93.2% of the 161 patients in the MRI arm were free of locoregional recurrence at five years, compared with 95.7% of the 158 patients in the no-MRI arm—a difference she described as not statistically different.

She stated that five-year distant recurrence-free survival and overall survival were similarly unaffected by whether patients had MRI, with values of 94.2% versus 94.4% for distant recurrence-free survival and 92.9% versus 91.4% for overall survival in the MRI and no-MRI arms, respectively. “The results from A011104 adds to the body of evidence that preoperative breast MRI for staging patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer does not result in improved oncologic outcomes or improvement in surgical care,” said Bedrosian, in the press conference at SABCS.

Bedrosian referenced the COMICE trial to note prior evidence that MRI did not reduce rates of subsequent surgery, then inferred that her results imply no clinical utility for routine preoperative MRI staging to guide surgical treatment in the studied context. She offered possible reasons: MRI may not have detected many additional lesions beyond mammography in this population, and/or identifying and removing those lesions may have had minimal impact on recurrence.

She also reviewed limitations, including that 93.4% of patients had clinically node-negative disease at baseline, which could contribute to low recurrence rates, and that the cohort skewed older, with a mean age of 58.9 years. It is possible that that MRI might benefit patients under 50 as they tend to have denser breast tissue. However, Bedrosian indicated that an analysis of participants under 50 suggested they similarly may not benefit from MRI. She added that the proportion of patients who underwent lumpectomy and received adjuvant radiation was comparable between arms.

The studies carry their own limits and contexts. Smidt noted incomplete five-year follow-up for all participants and the predominance of HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors 2 cm or smaller in the cohort, meaning the conclusions about SLNB omission are strongest in that group. She also pointed to the difficulty of applying the findings directly to partial-breast irradiation or other newer protocols without additional data. Bedrosian highlighted the high proportion of clinically node-negative disease and the older mean age at enrollment, both of which are relevant when interpreting recurrence rates and the generalizability of MRI’s lack of benefit in this trial.

Smidt’s and Bedrosian’s studies do not erase the complexity of decisions around breast cancer care. Smidt advocated for careful follow-up in HR-positive disease given the possibility of late recurrences, even in the context of low five-year recurrence rates; she also indicated that the applicability of SLNB omission to newer radiation protocols remains to be proven. Bedrosian acknowledged that MRI’s lack of impact on outcomes in her trial sits alongside clinical judgments about tissue density, patient age, and a multitude of other factors.

“There could be times where it is still important to do MRI—where patients with germline BRCA mutations or other germline carriers, and patients with atypical presentation of disease for example, could benefit,” she said.

Across these studies, the authors’ comments return to the same practical theme: clarity about when a test or procedure can add value for a given patient. These studies describe how “less” can be safe in precise contexts. “We need you to take the lead in implementing de-escalation because there’s a high chance that most patients will take your advice and will not understand the options unless you help them,” said advocate N. Beth Emery from the Alamo Breast Cancer Foundation, speaking to the attendees of the “Clinical Controversies: Management of the Axilla in Multidisciplinary Care” session.

These studies do not ask patients to accept less, or to accept different, on a whim. It is an effort by researchers to match the evidence to the patient in front of them, because omission and innovation are only as safe and useful as the context allows.

Learn about other treatment de-escalation strategies for cancer in this collection of posts from Cancer Research Catalyst.