Updated Guidelines Can Help Make Cervical Cancer Screening and HPV Vaccination More Convenient

This January, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRAS) updated cervical cancer screening guidelines to include at-home, self-collection tests, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued new recommendations to cut down the number of doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for some children—changes that will help make these prevention strategies for cervical cancer more convenient.

HRAS, which operates under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, now recommends that women 30 to 65 years old be screened every five years with high-risk HPV testing or cotesting with both Pap smears and HPV testing. If HPV testing is not available, then it is recommended women in this age range get a Pap smear every three years. Previously, the recommendation called for either cotesting every five years or Pap smears every three. For women between 21 and 29, the recommendation of Pap smears every three years remains the same.

This change means that 30- to 65-year-olds can now take advantage of recently approved self-collection methods for HPV testing without necessarily needing to get a Pap smear. In 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two tests that allow women to collect their own samples within a clinician’s office. And in 2025, the FDA approved the Teal Wand for at-home sample collection. Health insurance plans are required to cover screening tests recommended in the guidelines by the start of 2027, according to the HRAS.

HPV screening tests—which look for the 13 types of high-risk HPV known to cause more than 90% of all cervical cancer cases—have previously been found to have a higher sensitivity compared to Pap smears, according to a review published in Cancer Prevention Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). This means that these tests are better at detecting the presence of high-risk HPV strains; however, they are not as accurate at determining whether the infection is persistent. About 90% of HPV infections will clear up on their own, so if a high-risk HPV strain is detected, then additional testing is needed to determine if the infection is persistent and could lead to cancer.

Can At-home Testing Improve Cervical Cancer Screening Rates?

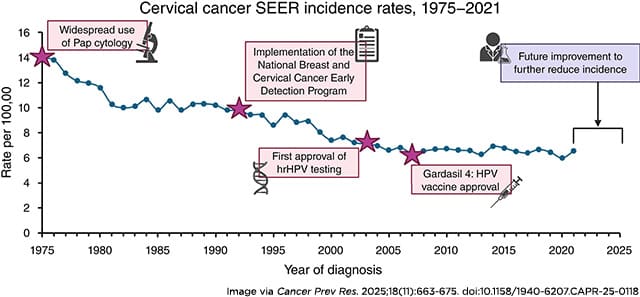

Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that could be almost entirely prevented, in part thanks to the available screening methods. However, as noted in the Cancer Prevention Research review, incidence rates for cervical cancer have been mostly stable over the past 20 years. This is following a nearly 50% decline between the 1970s, when Pap smears were introduced into the clinical workflow, and around 2005, a few years after the first HPV screening test was approved.

Last year, over 13,300 women in the United States were diagnosed with cervical cancer and more than 4,300 women died from the disease, according to federal estimates. While the five-year relative survival rate for cervical cancer is over 90% when detected at an early stage, it drops to around 20% once the cancer has spread—when about 15% of cases are diagnosed.

The CDC estimates that about 25% of women are not up to date on cervical cancer screenings, and the authors of the review point to several studies that show how screening rates are lower among rural women; those in certain racial groups (including Hispanic, American Indian/Native Alaskan, and Asian); and immigrant populations with a low proficiency in English. However, they speculate that the addition of an at-home test could help increase screening rates among these groups.

A study presented at the 18th AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities showed how this could be the case for foreign-born Asian American women. Carolyn Fang, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center—Temple Health, and her colleagues enrolled 1,140 Asian American women between ages 30-65 in an educational workshop on cervical cancer. While all women were provided referrals to sites with free or affordable screening options, half were also given an HPV self-sampling kit with instructions in English, Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese. Six months after the workshop, 87% of the women who received self-sampling kits returned a completed sample, while only 30% went to get a Pap smear at a clinic.

“Our findings indicate that a targeted, culturally sensitive, convenient, and private option really appealed to women, and may help us get closer to the ultimate goal of eliminating cervical cancer,” Fang said in a press release.

Updated Guidelines Recommend Just One Dose of HPV Vaccine for 11- and 12-year-olds

The availability of three FDA-approved vaccines to prevent infection with certain high-risk subtypes of HPV is another reason why it is possible to nearly eliminate the incidence of cervical cancer. Between 2008 and 2022, cervical precancer incidence (defined as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or CIN2+) decreased 79.5%, and higher-grade precancer incidence (CIN3+) decreased 80% in the United States among women 20-24 years old—the age group most likely to have been vaccinated during this period. Comparatively, CIN3+ decreased by 37% in women 25-29 years old, who were less likely to have been vaccinated during this time.

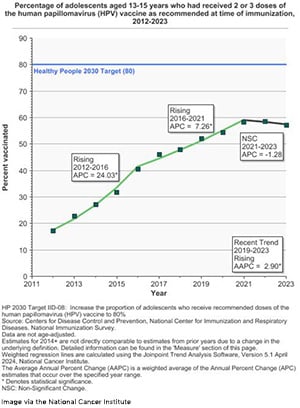

In recent years, however, the number of adolescents who are up to date on the HPV vaccine has started to decline, dropping from 63% in 2022 to 57.3% in 2023. The new updated recommendation from the CDC this month brings some good news. Previously, it was recommended that those under 15 should get two doses of an HPV vaccine and those between 15 and 26 years should get three doses. Now, it is recommended that children ages 11 to 12 only get one dose.

This is, in part, based on a recent study led by Aimée R. Kreimer, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, which found that one dose of an HPV vaccine was no less effective than two doses in protecting against HPV16/18 infection—the HPV strains responsible for 70% of cases of cervical cancer worldwide. In the 20-year study, 20,330 girls between 12 and 16 in Costa Rica were enrolled in a clinical trial and randomly assigned to receive either one or two doses of an HPV vaccine. Either dosage resulted in at least 97% vaccine efficacy.

“With single-dose vaccination and simplified screening, that is truly the pathway to accelerated cervical cancer control globally,” Kreimer said at the AACR Annual Meeting 2025, where the initial results from this study were presented.