Circulating Tumor DNA Levels After Preliminary Therapy May Better Predict Breast Cancer

ctDNA status may also inform treatment plan.

Breast cancer is the most common form of non-skin cancer in the United States, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer, or HER2-positive breast cancer, accounts for about 13% of breast cancer cases. This cancer is known to have a high recurrence rate, and clinicians typically look for whether patients have a pathologic complete response (pCR), or the lack of all signs in cancer tissue samples after treatment, as a predictor of their recurrence risk. However, researchers at the National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, found that circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be a better indicator of recurrence risk and even guide treatment, according to a study published in Cancer Research Communications, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

When cancer is described as HER2-positive, it means the cancer cells express the HER2 protein, which enables them to grow more quickly and spread to other parts of the body. This disease is typically treated with neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAT), or treatment given as a first step to shrink a tumor before primary treatments like surgery. After a primary therapy, patients often receive adjuvant therapy, which aims to prevent the cancer from coming back.

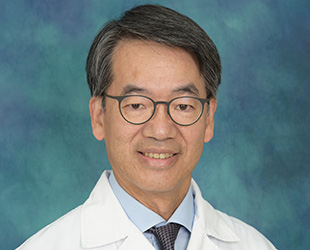

Despite some patients having pCR, they still experience recurrence, or even metastasis—which is the spread of cancer cells to other parts of the body—according to lead author Chiun-Sheng Huang, MD, PhD, MPH, professor of surgery and director of the Breast Care Center at National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. “This highlights the need for a better biomarker to identify which patients may experience disease recurrence,” he said.

Looking to ctDNA

Dr. Huang and colleagues, including first author Po-Han Lin, MD, PhD, sought to determine whether measuring ctDNA levels could serve as a prognostic predictor after NAT in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer.

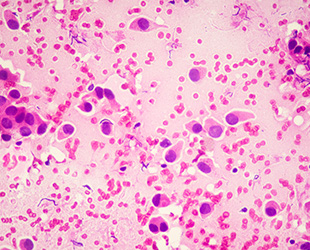

ctDNA is shed from tumors into the bloodstream and can provide a noninvasive way to glean insights about a patient’s cancer. To do this, researchers measure blood serum levels of DNA with genetic variants that tend to occur in tumors. “The ctDNA amount usually increases with disease burden, and the amount can decrease when the disease responds well to therapy,” Dr. Huang said.

To study the relationship between ctDNA and disease recurrence, the researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 117 patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer who had received NAT in the form of chemotherapy with single or dual anti-HER2 antibodies. Following surgery, 18 of these patients had received the antibody-drug conjugate therapy trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1, Kadcyla) as an adjuvant therapy, which has been shown to improve survival in patients who do not have pCR after NAT. Researchers collected blood samples from the patients before starting NAT and after surgery.

Of the total 117 patients, 79 patients (67.5%) were ctDNA-positive before NAT, and 32 of those 79 (40.5%) continued to test positive for ctDNA after NAT. Thirty-eight of the 117 patients (32.5%) tested negative for ctDNA before treatment, and all 38 of them remained ctDNA-negative after NAT.

Overall, 25 patients (21.4%) had a pCR after NAT, compared with 92 (78.6%) who did not. Of the 25 patients with pCR, six (24%) tested positive for ctDNA after NAT. In the 92 patients who did not experience pCR, ctDNA was detected after NAT in 26 (28%) patients.

Among the 99 patients not treated with T-DM1, patients who were ctDNA-positive after NAT were 5.5 times more likely to experience disease recurrence than patients who were ctDNA-negative within the median 4.02 years of follow-up, regardless of pCR status. Further, recurrence-free survival (RFS) was not statistically different between ctDNA-negative patients with pCR and ctDNA-negative patients without pCR, nor between ctDNA-positive patients with and without pCR. This suggested that ctDNA may be a more accurate predictor of disease recurrence than pCR, said Dr. Huang.

Among the patients not receiving T-DM1, 62 patients were ctDNA-positive before NAT. Forty of the 62 patients had ctDNA clearance after NAT, and patients with ctDNA clearance experienced significantly better RFS than patients with ctDNA that persisted after NAT. Of the total 117 patients in the analysis, 18 patients without pCR received adjuvant T-DM1 therapy. During serial tests, adjuvant T-DM1 therapy led to significantly higher ctDNA clearance rates (8/8) than non-T-DM1 therapy (7/12) in patients who were ctDNA-positive after NAT.

The researchers further compared RFS among four patient groups—ctDNA-negative/non-T-DM1 (n=77), ctDNA-negative/T-DM1 (n=8), ctDNA-positive/non-T-DM1 (n=22), and ctDNA-positive/T-DM1 (n=10). Of these, only the ctDNA-positive/non-T-DM1 group experienced a significantly worse three-year RFS than the others. All eight ctDNA-negative patients who received T-DM1 adjuvant therapy lived without any observed recurrence during a median 3.3 years of follow-up.

A Potentially Important Tool for Clinicians

These results suggest that adjuvant T-DM1 could benefit patients who test positive for ctDNA after NAT and surgery, potentially independently of pCR status, Dr. Huang said. Conversely, patients who test negative for ctDNA may not experience any added benefit from adjuvant T-DM1.

“Our findings indicate that ctDNA could be a better prognostic factor than pCR in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer after they’ve received NAT. We believe that this knowledge could be effectively used to guide escalation or de-escalation of adjuvant therapy,” said Dr. Huang.

“However, these implications need to be verified by further large-scale studies or randomized trials,” said Dr. Huang. The study’s limitations include its retrospective design, a limited sample size, and the possibility of confounded ctDNA reads due to the sequencing methods used.