Archives: Pillars

Can cancer early detection and prevention strategies have a significant impact on reducing the global burden of cancer? The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and its members have long focused on finding better ways to detect cancer in its earliest stages—or preventing malignancies from developing altogether.

Fellow of the AACR Academy Kornelia Polyak, MD, PhD, first became fascinated by the molecular processes behind cancer when her high school biology teacher gave her a book by Nobel laureate Albert Szent-Györgyi. Even then, it made perfect sense to her why this should be a key area of research, why understanding how tumors progress would lead to better ways to intercept disease in early stages, treat later-stage disease, and perhaps even prevent cancer in the first place. Yet, she heard a common response when she started her research in this field more than 25 years ago: Why should we care?

“Not many people studied early-stage disease then,” Dr. Polyak, now a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a co-leader of the Cancer Cell Biology Program at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, explained. “I remember I got so many rejections. They would just say that early-stage disease is not killing people.”

But thanks to the work of Dr. Polyak, whose pioneering research was recognized with her election to the AACR Academy in 2020, and other dedicated researchers, early detection and prevention have become key components in cancer research—the importance of which has only continued to be amplified over the years. While the AACR has long featured leading-edge research in these areas within its 10 peer-reviewed medical journals and at conferences around the world, it established the AACR Cancer Prevention Working Group in September 2021 to help ensure cancer prevention is a global priority. This is being achieved through the support of innovative science, integration of the latest technologies, improved levels of funding, and the development of public education and awareness strategies.

Early detection and prevention were also included among the eight goals of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) National Cancer Plan, which was announced in April 2023. About a year later, President Joe Biden proclaimed April 2024 as National Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Month.

“We have no choice but to put a lot of attention on prevention and early detection,” NCI Director Kimryn Rathmell, MD, PhD, said at the AACR Annual Meeting 2024. “That’s where we’re going to get the best mileage—the best cancer is one that never happens.”

To help make this goal a reality, researchers are working in several areas related to prevention, detection, and treating early-stage disease including liquid biopsy, multi-cancer early detection (MCED), cancer interception, and population science. The AACR Annual Meeting 2024, held April 5-10 in San Diego, featured talks and studies from many researchers in these fields providing the latest updates on their work.

The incidence of cancer around the world is expected to increase from 9.7 million in 2022 to 18.5 million by 2050, and five-year survival rates are significantly higher in early stages compared to later stages, with figures varying by cancer type. Those two statistics highlight why researchers feel the need to expand beyond or improve upon current screening options. One way to do this is through liquid biopsies, in which tests—typically of a person’s blood—can detect potential evidence of cancer.

For example, Ajay Goel, PhD, chair of the Department of Molecular Diagnostics and Experimental Therapeutics at City of Hope, and his team announced findings at the Annual Meeting regarding their exosome-based liquid biopsy test for pancreatic cancer. As Dr. Goel noted, currently no tests are available to screen for pancreatic cancer in its early stages even though finding the disease before it has metastasized can mean a five-year survival rate of 40%, compared to 3% once the cancer has spread.

His team’s test combines the unique markers on the surface of exosomes—vesicles expelled by cells into blood—that make it easy to see where they came from with cell-free DNA markers found in the blood of patients with pancreatic cancer. In 139 patients with pancreatic cancer and 193 healthy donors in the United States, the test accurately detected 97% of stage 1-2 pancreatic cancers when combined with a known pancreatic cancer marker, CA19-9.

For ovarian cancer—another cancer type lacking early screening options—Victor Velculescu, MD, PhD, FAACR, and his team presented an update on their DELFI test, which uses a different method of liquid biopsy analysis called fragmentomics. This approach aims to detect changes in the size and distribution of cell-free DNA fragments across the genome within the circulation. Since patterns of DNA fragments can be different in patients with and without cancer, Dr. Velculescu and his colleagues are trying to use artificial intelligence/machine learning to distinguish which patterns could indicate if someone has ovarian cancer.

When analyzing plasma from 134 women with ovarian cancer, 204 women without cancer, and 203 women with benign adnexal masses, their test identified 69% of cases in stage 1, 76% in stage 2, 85% in stage 3, and 100% in stage 4. In comparison, women at higher risk of ovarian cancer can get a blood test for the CA125 tumor marker, which detects 40%, 66%, 62%, and 100% of cases at stages1-4, respectively.

Both Drs. Velculescu and Goel are working to validate their respective tests in larger cohorts before they become available.

“The important thing to keep in mind: These are screening tests—not diagnostic tests,” said Dr. Velculescu, a professor of oncology and co-director of the Cancer Genetics and Epigenetics Program at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. “They’re not meant to definitively say you have cancer. They’re meant to get people into a pathway that already exists with multiple steps [that lead to diagnosis]. So, for screening to work, it’s got to be accessible, … inexpensive, … easy to do, [and] available to everybody.”

Another application of liquid biopsy discussed during the meeting was MCED, for which tests are being developed to screen for many cancers at once. For example, the Galleri test from Grail is designed to detect a shared signal associated with 50 cancer types, most of which have no guideline-recommended screening, according to Charles Swanton, MD, PhD, FAACR, the deputy clinical director at The Francis Crick Institute and a member of the advisory board for Grail. At the moment, no MCED test has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but some are available as lab-based tests.

Swanton presented four-year follow-up data from the Circulating Cell-free Genome Atlas (CCGA) Study evaluating the effectiveness of Galleri. Among the 2,513 participants with cancer, the Grail test detected a cancer signal in 85% of the 31% of patients who died during follow-up compared to a 35% detection rate in the 69% who were alive at follow-up. The assay also often failed to detect signals from already commonly screened cancers such as hormone receptor-positive breast cancer and prostate cancer, according to Dr. Swanton.

“It’s early days, but I could see a future where assays such as this may be complementary to standard of care screenings—definitely not substitutional,” Dr. Swanton said.

In February 2024, the NCI launched the Cancer Screening Research Network (CSRN) to evaluate new methods of cancer screening. This will include an examination of MCED tests through the upcoming Vanguard Study, which will first enroll up to 24,000 people to help inform the design of a larger randomized controlled trial.

“As a practicing medical oncologist, I applaud the NCI for having this initiative,” said AACR President 2024-2025 Patricia M. LoRusso, DO, PhD (hc), FAACR, a professor of medicine at Yale University and associate cancer center director, experimental therapeutics at the Yale Cancer Center. “There are a lot of different tests out there—many of them haven’t been well validated in the relevant clinical trials. The plan that the NCI is promoting is going to help us understand how best to utilize those, so that they can eventually … be more meaningful and predictive.”

Daniel De Carvalho, PhD, a professor at University of Toronto and researcher at the Princess Margaret Research Centre, who chaired a plenary on “Discovery Science in Early Cancer Biology and Interception,” explained another future benefit of these MCED tests.

“They not only detect cancer, but they bring insights about the biology of that cell that are releasing this DNA,” Dr. De Carvalho said. “As these tests are deployed in large population studies and especially in screening the population [at large], these may create some of the most important data sets for artificial intelligence as we use these to understand biology and cancer formation.”

Once researchers better understand the mechanisms behind cancer formation, they can identify potential targets for earlier intervention. This is called cancer interception, which Dr. De Carvalho compares to a fire alarm. He imagines the possibility of developing a surveillance system to monitor for the mechanisms behind the creation of cancer cells that can then be activated to suppress this process. For example, he has been studying if viral mimicry, a method typically used to treat cancer, can be used for early detection. With viral mimicry, a cancer cell is tricked to look like a virus-infected cell, which can trigger an antiviral response.

“Interceding when the cancer is early in development is going to be much more effective than fully preventing cancer from developing,” explained Kara Maxwell, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Maxwell, one of the AACR Annual Meeting 2024 NextGen Stars, is studying women with breast cancer who have germline p53, BRCA1, or BRCA2 mutations. She presented research on the tumor evolution in TP53-driven breast cancers, which she hopes could lead to utilizing targeted immunotherapies to intercept cancer as an alternative to surgery.

“Surgery doesn’t always treat everybody, even when we think it’s a very early stage, because the cancer has metastatic potential,” she explained. “What we’d like to do on the immune side may be more beneficial because it could hopefully attack the cells not only in the breast where they started, but also those cells that got out. It just speaks to the importance of understanding those early mechanisms to figure out which people have [tumors with] early metastatic potential.”

Dr. Polyak, who also studies germline p53, BRCA1, or BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer, has been researching the impact of aging on cancer to better understand what factors can predispose people to disease. Along with her team, they identified a cytokine, known as midkine, that appears to correlate with breast cancer risk. Dr. Polyak hopes this could be used as a target for prevention. Separately, her team is also working on a vaccine that uses mRNA technology, similar to the COVID-19 vaccines, to target early progenitors from which tumors initiate.

But she is also just excited to see more people working to understand how multiple factors such as ethnicity, age, obesity, lifestyle, genetics, immunology, environment, the microbiome, and others can impact the development of cancer.

“Many factors that we can easily measure can be incorporated into an overall risk prediction strategy,” Dr. Polyak said, “because to apply prevention, you have to identify the high-risk individuals with high accuracy.”

Roel Vermeulen, PhD, a professor of environmental epidemiology and exposome science at Utrecht University and the UMC Utrecht and scientific director of the Institute for Preventive Health in the Netherlands, estimated that we currently know about half of the modifiable factors behind cancer—and that the task to further our understanding will be daunting. In terms of chemical exposure alone, among the 100,000 chemicals on the market, about 500 have been well characterized to cause human disease and about 10,000 to 20,000 have a partial assessment of what they could do. This leaves about 70,000 with a dearth of information.

To address this, Dr. Vermeulen and his team are working on a project to systematically map what they call the external exposomes, basically all the variables a person is exposed to that could cause cancer, including smoking, alcohol, physical activity, the built environment, the green space around you, the social environment, chemicals, air pollution, pesticides, and much more.

“This is a large effort to stitch together multimodal data coming from different sources … to really come to the elucidation of which factors are important for the cancer burden that we see,” he explained.

Yin Cao, ScD, MPH, associate professor of surgery and associate professor of medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine, is part of another project with a similar goal. Team PROSPECT, which was awarded funding through the Cancer Grand Challenges—founded by Cancer Research UK and NCI—to address the Early-onset Cancers Challenge, will look to advance actionable prevention among younger generations. This will include defining exposomes related to early-onset cancers and implementing prevention trials to see how to engage younger populations in the most effective and equitable way.

“We need to focus on something common, modifiable, relevant for the younger generation,” Dr. Cao explained. Since most recommendations for screening for people with average risk of cancer start around 40 to 50 years old, Dr. Cao and her colleagues are looking at what factors may be contributing to the rise of early-onset cancer that younger people can act on now and how to best educate them about what they find.

Dr. Cao saw the impact of such education in a small way when her friend’s 13-year-old daughter stopped drinking sugar-sweetened beverages immediately after Dr. Cao showed her a study on the association between these beverages and early-onset colorectal cancer.

“When we bring cancer as a word to younger generations … they feel like [it] is super important,” Dr. Cao said.

As research in this area advances and more screening options for cancer become available, it is also important to ensure people understand when screening is most appropriate and what the results mean should they decide to get screened.

“Not all early cancer diagnoses are helpful,” Dr. Maxwell said. “We know in many instances, such as in prostate cancer and breast cancer, that we may be overtreating. As oncologists, one thing [we can do] is educate the public and, frankly, providers, to understand risk.”

For example, Dr. Maxwell said her patients don’t often understand that even if they have gene alterations associated with cancer, it does not mean their chances of getting the disease are 100%. She stressed the importance of helping to frame those results and walking people through the benefits and risks of their next steps, such as undergoing a bilateral mastectomy to prevent breast cancer versus continuous screening.

“Cancer is a major public health issue,” Dr. Polyak said. “Research is the only way we can make progress and improve treatment, early detection, and hopefully prevention. We need the support of government, and at the same time, the public needs to understand the risk factors for cancer, the steps they could potentially take to decrease their own risk, and the early detection methods available to them. We know early detection makes a big difference in outcomes, so educating the public about those tools would have a great impact.”

Preventing cancer and identifying malignancies at the earliest, most treatable stages are key areas of focus for the American...

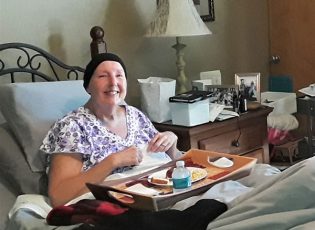

For Margaret McGill, palliative care was key to her cancer care, enabling her to regain her quality of life and reach her goal of undergoing a bone marrow transplant.