One Size Doesn’t Fit ALL: Dynamic Approaches to Childhood Leukemia

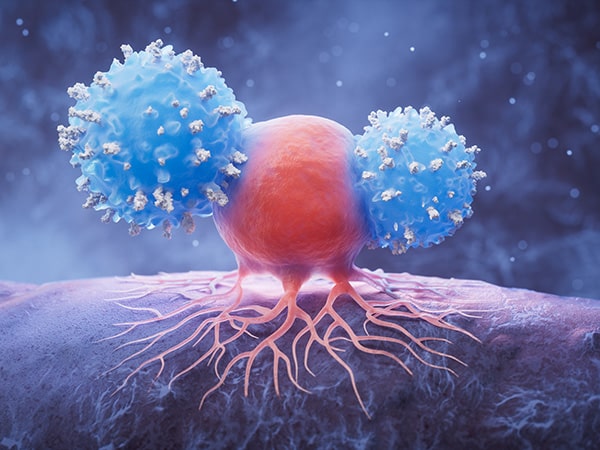

The past decade has delivered some very welcome news for children with leukemia, as approvals for several sophisticated treatments—including approaches that use bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy—have continued to be announced. But these cutting-edge leukemia treatments are no sure thing in many parts of the globe, and for many families in lower-income countries, even basic cancer treatment may be out of reach. How, then, does one pragmatically approach the need for treating childhood leukemia in non-high-income countries, where the first treatment offered may represent the only available option?

Enter Shawn H.R. Lee, MD, PhD, whom the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation honored as the recipient of the 2024 AACR-St. Baldrick’s Foundation Pediatric Cancer Research Grant. Lee received the award for his work on precision medicine in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), with potential broader applicability to resource-limited settings.

As a consultant pediatric oncologist at the National University Hospital and an adjunct assistant professor at the National University of Singapore, Lee investigates treatment outcomes in pediatric ALL cases with an emphasis on how adjusting treatments according to individual genetic profiles can improve outcomes.

With the grant supporting his continued research on personalized therapies for childhood patients with ALL in Southeast Asia, Lee presented on this work by delivering the awardee lecture at the AACR Special Conference in Cancer Research: Discovery and Innovation in Pediatric Cancer—From Biology to Breakthrough Therapies in Boston, held September 25-28.

Cancer Research Catalyst covered Lee’s presentation and spoke with him about how his AACR- and St. Baldrick’s Foundation-sponsored research is helping children living with ALL in Southeast Asia. The takeaway: According to Lee, improved survival depends on treating ALL not as a standard-issue, by-the-numbers disease but as a cancer deeply influenced by individual genetic factors, along with genetic ancestry and socioeconomic setting. Especially in areas with more limited medical resources, said Lee, personalized approaches for childhood ALL can make all the difference.

“My training in the United States exposed me to the true frontiers and cutting edge of research and precision oncology,” Lee said. “But in Southeast Asia, sometimes even access to basic care is limited, let alone next-generation therapies and personalized treatment. It is therefore a novel and exciting challenge of bridging the West and our Southeast Asian region, to try to adapt modern contemporary approaches to the economic realities of our region.”

Partnership Powering Progress: International Teamwork Against Childhood Leukemia

Through international collaborations, clinical trial networks, and a growing focus on precision medicine, Lee and his colleagues are working to reshape treatment for children with ALL with an eye for maximizing efficacy at the individual level. For background, Lee presented his work on genetic ancestry, ALL molecular subtypes, and prognoses of childhood ALL cases, which included patients from around the globe: the United States, Guatemala, Malaysia, and Singapore.

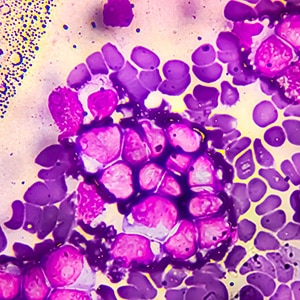

The study found that ALL variants’ distribution in patients could be traced to individuals’ genetic ancestry. By grouping the genetic ancestry analysis of Asian patients into more specific South Asian and East Asian cohorts, Lee and his colleagues found that the two groups tended to have distinct genetic profiles of ALL, and he noted in his talk that the South Asian patients in particular tended to respond exceedingly well to ALL treatment.

That same study also provided evidence of genetic ancestry’s association with treatment outcomes. Children of East Asian ancestry, for example, more frequently exhibited genetic subtypes associated with good eventual outcomes to ALL treatment (such as the DUX4 subtype), and patients with Native American or African ancestry more often carried higher-risk, poorer-response-associated genetic subtypes (such as the CRLF2 or Ph-like subtypes). The fact that ALL’s treatment-response phenotypes are associated with different genetic ancestries, Lee said, helps explain why outcomes vary and highlight the challenges of adapting protocols developed in one part of the world into another region where patients’ disease composition can differ so greatly.

Even after accounting for known risk factors, Lee said in his talk, genetic ancestry itself remained tied to survival outcomes. For him, the message was simple: Pediatric cancer care must be regionally adapted and designed to fit population contexts, not simply translated from a vastly different part of the world to another.

He pointed to the 2003 and 2010 Malaysia–Singapore (Ma-Spore) trials that incorporated genetic insights into the development of patient-specific approaches. Lee emphasized the importance of the findings that children whose ALL had certain high-risk markers received more intensive therapy, whereas others without had their treatment reduced to spare them unnecessary side effects—a demonstration of the Ma-Spore ethos, “curing the curable.”

Treating Cancer to a T: Addressing the Challenge of T-cell ALL

Progress, however, has not been equal for patients with pediatric ALL, Lee said. While outcomes for B-cell ALL have steadily improved, T-cell ALL remains a challenge, which prompted Lee to plumb the depths of genetic ancestry in T-cell ALL. As reported in Blood Cancer Discovery, a journal of the AACR—in a study led by Haley Newman, MD, and David Teachey, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in collaboration with Lee and other colleagues—researchers examined data from more than 1,300 young patients treated in the United States, and they found that the usefulness of established prognostic genetic mutations as indicators of treatment efficacy may differ by patients’ ancestry.

For example, mutations in the NOTCH1 gene were able to predict improved event-free survival in European patients with pediatric T-cell ALL, but those same mutations failed to predict the prognosis of African patients. Without accounting for these differences, Lee said, risk models could misclassify children, leading to either over- or undertreatment. The study underscores why ensuring global representation in research is so important. Only by including children from diverse backgrounds can doctors build accurate, equitable models of care.

Taking Cancer Personally: Tailoring Therapies to Patient Genetics

Lee’s latest efforts attempt to personalize the clinic for individual patients through the use of functional profiling during the normal course of treatment. This approach, also known as pharmacotyping, tests each patient’s leukemia cells directly against a panel of drugs in the lab to see which treatments are most effective for each child, which allows for a tailored approach.

Lee demonstrated how he and his colleagues have used pharmacotyping to reveal dramatic differences in drug sensitivity across leukemia subtypes, including a T-cell ALL subtype that, despite its generally poor prognosis, responded well to targeted therapy. These differences, he said, helped predict which patients were likely to respond well to standard therapies—and which might need alternative treatments. Pharmacotyping also pointed to opportunities for targeted drugs in specific subsets of patients, suggesting new ways to match the right therapy to the right child.

Lee credits the AACR-St. Baldrick’s Foundation Pediatric Cancer Research Grant with helping to make this vision a reality in Southeast Asia. With the grant’s support, Lee said, he has begun to establish pharmacotyping workflows in Singapore. He aims to integrate this technology into frontline care so that a child’s first treatment is guided not just by general risk categories but also by their responses to leukemia therapy. Functional profiling, according to Lee, has the potential to refine risk stratification and improve outcomes, while sparing children from unnecessary toxicity.

“The AACR-St. Baldrick Foundation grant has been invaluable in helping me bring this imaging-based pharmacotyping that I learned in the United States while at St. Jude to Singapore and Southeast Asia,” said Lee. “The grant has helped us establish and develop our assay, workflows, and start pilot studies. We are firmly on our way to our goal of bringing this to frontline treatment.”

Outcomes, Outcomes, Outcomes: Focusing on Survival for Childhood ALL

According to Lee, for families dealing with their child’s diagnosis of ALL—especially in lower income countries—the first round of treatment often represents the only chance at clearing the cancer. Therefore, he considers his work guided by this reality: Protocols must maximize the chance of survival while minimizing long-term harms, which can post substantial risks to survivors of pediatric cancers.

Finding the right balance of curing without overtreating has already changed lives in some cases. Lee pointed to his predecessors’ successful work on the Ma-Spore trials, in which more than 90% of patients with B-ALL survived at least five years. With new tools like pharmacotyping, he intends to extend those gains to more children with more difficult subtypes of leukemia.

By linking recognition of senior investigators with grants for junior researchers, he said, the award strengthens mentorship and ensures that discoveries do not stop with one generation. As Lee sees it, his own career was shaped by mentors who perform both basic and translational research in childhood leukemia, and he is now committed to guiding others as they take pediatric cancer research in new directions.

“Mentorship has been very important to my career development, and it might well have been the most important factor in my becoming a researcher,” he said. “I believe that the mentor-mentee relationship is absolutely crucial, especially for a young clinician-scientist with a growing career. My boss in Singapore, Allen Yeoh, MD, and my boss at St. Jude, Jun Yang, PhD, are the two giants in their fields who have made this journey possible.”

Progress in childhood cancer depends on breakthroughs in the lab, but if those breakthroughs don’t make it to patients, what good are they? By building networks of scientists who can adapt discoveries to the diverse realities that patients face around the world, researchers like Lee are working to weave a robust web of cancer care that can protect many more children.