Cardio-oncology: Treating Cancer Without Harming the Heart

Cancer medicine has never been more powerful, or more complex. Modern drugs can melt tumors that once seemed unbeatable, and survival rates for many cancers keep climbing. Yet while newer treatments often have preferable side effect profiles compared to chemotherapy, they can affect some of the body’s most vital organs, including the heart.

Cardiotoxicity can come in many forms, and sometimes does not manifest until decades later, something Peter Wolf learned after a yearslong quest for answers related to valve disease rooted in radiation treatment for lymphoma in his teens.

Cancer and cardiovascular disease already claim the top two spots on the U.S. mortality list, and cancer survivors face about a 42% higher risk of heart problems compared with people who have never had cancer. The ultimate goal is not a Pyrrhic victory but a lasting one: eliminate the cancer and let patients enjoy a better quality of life with healthy hearts.

The Importance of Healthy Cardiovascular Highways

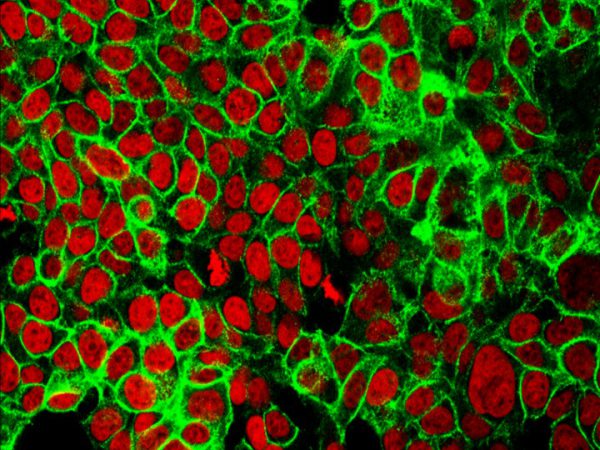

Think of the endothelium—the single-cell layer lining every artery, vein, and capillary—as the pavement of the body’s circulatory highways. When healthy, it keeps blood (and the circulating immune cells) gliding smoothly where they need to go, widening or narrowing lanes as necessary and preventing fender benders that could clog the road. But new generations of treatments for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) can turn parts of a once-smooth pavement into hazard-filled stretches with potholes prone to pileups and clots.

Approved in 2001, imatinib (Gleevec) became the first small molecule precision therapy, and created a new class of treatments known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Instead of indiscriminately targeting dividing cells, imatinib homes in on an abnormal fusion protein called BCR-ABL. This protein is created by the Philadelphia chromosome, an accidental DNA swap between two chromosomes that characterizes roughly 95% of CML cases. For many patients, imatinib transformed CML from a deadly disease into a long-term, manageable condition.

But cancer sometimes finds ways to escape; by acquiring BCL-ABL mutations that weaken the grip of imatinib, for example. Enter the next-generation TKIs. These treatments, such as dasatinib (Sprycel), nilotinib (Tasigna), and ponatinib (Iclusig), latch onto BCR-ABL differently and, in ponatinib’s case, can even overcome some mutations that provide resistance against other TKIs. However, they can also come with greatly increased risks of heart attack, stroke, or limb-threatening clots.

Why the difference?

According to Iris Jaffe, MD, PhD, the Elisa Kent Mendelsohn Professor of Molecular Cardiology and executive director of the Molecular Cardiology Research Institute at Tufts Medical Center, the trouble traces back to blood vessel inflammation.

At the AACR Annual Meeting 2025, Jaffe highlighted how endothelial cells exposed to ponatinib clung to platelets much more readily, and in mice that develop human-like atherosclerosis when fed a high-fat diet, ponatinib increased inflammation, immune cell trafficking (both T cells and myeloid cells), and unstable fatty plaques.

Most strikingly, ponatinib invariably led to cardiovascular events or death in a novel plaque rupture model, whereas imatinib caused similar fates only 20% of the time. Interestingly, asciminib (Scemblix), a new TKI and the first to target tyrosine kinase enzymes in CML in an allosteric fashion, meaning it doesn’t target the active binding site, led to similar survival rates as imatinib in mice, and also appeared to spare their endothelium.

In follow-up experiments, Jaffe and her colleagues revealed that blocking the inflammatory switch TNFR2 could calm the endothelial lining and protect against cardiovascular events, hinting at the possibility of strategies to neutralize this vascular toll without sacrificing anticancer power.

As far as how the different TKIs affect the signaling of specific tyrosine kinase pathways, no single kinase alterations stood out, so the team sought to capture the “fingerprints” left behind by different TKIs that reflect how they influence kinase activity more globally in these endothelial cells. By comparing these TKI fingerprints to those of 30 already approved cardiovascular drugs the researchers hope to identify therapies with opposing signatures that might be able to counteract specific TKI-induced cardiotoxicity, though distinct TKI signatures would likely demand different cardiotoxicity counterbalancing strategies.

Age is another factor that impacts risk, Jaffe noted. CML usually appears after midlife, and consequently, more than 60% of patients already have hypertension, diabetes, or coronary disease at the time of diagnosis. She noted that having just one of those risk factors doubles the likelihood of a drug-induced clot, meaning the treatment that rescues an older patient from leukemia can unmask a silent vulnerability in arteries already under strain.

“The Weakest Link”

Why are endothelial cells so fragile in the first place?

One answer, according to Kristopher Sarosiek, PhD, a principal investigator and associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, might be their unique susceptibility to apoptosis, a built-in program that allows cells to quietly self-destruct if they sustain too much DNA damage, for example.

Picking up the thread where Jaffe left off during the “Cardio-Oncology: A Novel Platform for Investigation” Major Symposium, Sarosiek revealed how he and his colleagues used a method called BH3 profiling to learn that endothelial cells remain “primed” for apoptosis throughout the lifetime of mice. Heart-muscle fibers, liver cells, and other functional (parenchymal) cells, in contrast, seemed to grow tougher with age. That intrinsic sensitivity could explain why chemotherapy and radiation, which can damage DNA, often disrupt the vascular lining first. This makes them, in Sarosiek’s words “the weakest link” when it comes to toxicity.

In young mice—whose endothelial cells, in addition to their heart muscle cells, were particularly primed for apoptosis—the chemotherapy doxorubicin compromised heart function, unless the researchers disabled the BAX/BAK proteins that trigger apoptosis.

Shielding endothelial cells, whether by tweaking drug schedules, adding protective medications, or engineering smarter molecules, could allow doctors to preserve heart health without dialing back cancer-killing potency. To complement those potential solutions in the meantime, biomarkers that help predict who is most at risk of cardiotoxicity would be valuable in guiding vulnerable patients to avoid certain therapies, Sarosiek said.

When the Immune System Misfires on the Heart

Beyond endothelial damage due to cytotoxic drugs, immunotherapies like immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can also unleash cardiovascular damage. ICIs unleash T cells by removing molecular brakes such as PD-1 or CTLA-4. While these immunotherapies have been transformative for many types of advanced cancers, in about 1% of recipients they trigger myocarditis, an inflammatory attack on the heart muscle itself.

That 1% looms large, however, as the cardiotoxicity proves fatal in roughly 40% of cases, making ICI-induced myocarditis the most lethal immune-related side effect, according to Javid Moslehi, MD, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) William Grossman Distinguished Professor in Cardiology and chief of cardio-oncology and immunology at UCSF Health. In addition to founding the UCSF Myocarditis Center, Moslehi also leads the International ICI-Myocarditis Registry that, as of April 2025, had tracked nearly 1,300 cases from 150 centers across 26 countries.

The registry’s analyses have linked increased risk to combination regimens, in particular the dual administration of ICIs targeting LAG-3 and PD-1. To unravel the biology, Moslehi and colleagues utilized mice missing one copy of CTLA-4 and both copies of PD-1, both crucial immune checkpoints. Every such mouse died of myocarditis, driven by T cells that mistook alpha-myosin, a heart-specific protein, for a target. The other arm of adaptive immunity also plays a role, with a study in the AACR journal Cancer Immunology Research showing that B cells contribute to ICI-induced cardiotoxicity through the production of heart-targeting antibodies.

Standard steroids often prove ineffective in patients with ICI-induced myocarditis, among other hurdles, so Moslehi and his collaborators have been exploring a two-drug, immune-modulating rescue approach previously highlighted on the AACR blog. During this session, Moslehi shared clinical updates from his colleague Joe-Elie Salem, MD, PhD, an associate professor at Sorbonne Université in Paris, that demonstrated a potentially valuable approach for patients with ICI-induced myocarditis: combining abatacept (Orencia), which is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, with ruxolitinib (Jakafi/Opzelura), a drug with applications in graft-versus-host disease, dermatitis, and vitiligo.

Discussing the study in which myocarditis deaths were limited to about 2% in the first 90 patients using this combination, Moslehi said, “Again, not a randomized trial, but it’s perhaps a cocktail that one could use in our patients.”

Searching for Solutions for Survivors

Roughly 5.4% of the population in the United States—about 18.6 million people—are cancer survivors. Cardiovascular complications already rank as their second-leading cause of long-term death, and is the leading cause in long-term survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers. Even modest advances in cardio-oncology could bring huge gains in quality years. As the mechanisms mediating cardiovascular side effects become better understood, doctors will better be able to tailor their care, or at least monitor patients who might be at risk, to intervene early with any necessary countermeasures.