Screening Reduces Lung Cancer Mortality but is Underutilized

Screening for lung cancer using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was introduced in the United States in 2013. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that only one in eight people for whom lung cancer screening was recommended reported having been screened in the past year, even as long-term results from a large randomized clinical trial provided confirmation that screening reduces lung cancer death rates.

What is lung cancer screening and who should be screened?

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States—more than 135,000 people are anticipated to die from the disease in 2020 alone. The disease is also one of the deadliest types of cancer—fewer than 20 percent of patients survive five or more years after their diagnosis.

One reason that lung cancer is so deadly is that more than 75 percent of patients are diagnosed when the cancer has spread beyond the lungs, which makes it much harder to treat successfully. Detecting lung cancer at an early stage, when it is confined to the lungs, is one approach to reducing lung cancer mortality.

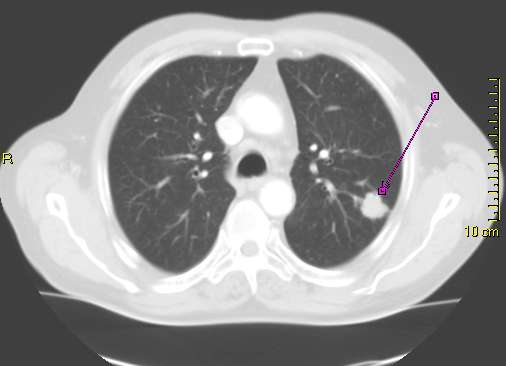

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) began recommending annual screening with low-dose CT for individuals at high risk for developing lung cancer in 2013. Low-dose CT uses low doses of X-rays to image the lungs. Individuals classed as having high risk for lung cancer are adults ages 55 to 80 who have smoked at least one pack of cigarettes a day for 30 years, or the equivalent (two packs per day for 15 years, etc.), and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.

Lung cancer screening reduces lung cancer mortality

The USPSTF decision to recommend lung cancer screening was based in part on results from the large randomized National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), which showed that screening with low-dose CT reduced lung cancer mortality in high-risk individuals by up to 20 percent.

Given that three other smaller trials with limited statistical power did not show that lung cancer screening was beneficial, researchers designed another large randomized trial to evaluate the ability of lung cancer screening to reduce lung cancer deaths. The Nederlands–Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek (NELSON) trial had 13,195 male and 2,594 female participants ages 50 to 74, all of whom were current or former smokers. Screening took place at enrollment and then after one year, three years, and 5.5 years.

After a minimum of 10 years of follow up, men enrolled in the NELSON trial who underwent screening were 24 percent less likely to have died from lung cancer compared with men who were not screened, according to data published recently in The New England Journal of Medicine. Among women in the trial, the benefit of screening was greater than it was for men (33 percent reduction in lung cancer mortality), however, the number of women in the trial was small and the difference not statistically different.

The benefit of screening was predominantly driven by the fact that a much higher proportion of the lung cancer cases diagnosed among the men who were screened for lung cancer were diagnosed at the earliest stages, stage IA or IB, compared with the lung cancer cases diagnosed among the men who were not screened. In fact, 58.6 percent of the lung cancers detected by screening were stage IA or IB but only 13.5 percent of the lung cancer cases diagnosed among the men who were not screened were stage IA or IB.

Uptake of lung cancer screening is suboptimal

Despite the benefits of lung cancer screening, a recent study by the CDC found that just 12.5 percent of adults who met the USPSTF criteria for lung cancer screening reported having had low-dose CT to check for the cancer in the past year.

The CDC study used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which is an annual telephone survey to collect state data about health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services by U.S. adults age 18. In 2017, the states had an option to include questions on lung cancer screening. Ten states opted to use these questions.

Among the 33,137 adults ages 55 to 80 who were asked the lung cancer screening questions, 12.7 percent met the USPSTF criteria for lung cancer screening, 32.1 percent were current or former smokers who did not meet the USPSTF criteria for lung cancer screening, and 55.3 percent were “never smokers.” Rates of lung cancer screening among adults who met the USPSTF criteria for screening varied by state, ranging from 9.7 percent in Oklahoma to 16.0 percent in Florida.

In addition to suboptimal uptake among individuals for whom lung cancer screening is recommended, 7.9 percent of current or former smokers ages 55 to 80 who did not meet the USPSTF criteria for lung cancer screening reported being screened for the cancer.

The low rates of lung cancer screening among those for whom it is recommended and the screening of individuals for whom it is not recommended highlight the need for new strategies, legislation, and public policies to improve lung cancer screening awareness. A study in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention suggests that one reason for suboptimal implementation of lung cancer screening is that rates of physician-patient discussions about such screening are very low. In fact, only 4.3 percent of all adults and 8.7 percent of current smokers reported talking with their doctor about having a test to check for lung cancer in the past year.

In an AACR press release on the study, the lead author, Jinhai (Stephen) Huo, PhD, MD, MSPH, said, “More physicians need to initiate a shared decision-making process with their patients who want to have or are eligible for lung cancer screening to reduce the risk of mortality associated with lung cancer. For eligible high-risk smokers, a low-dose CT scan can reduce the risk of mortality. For moderate- and low-risk smokers, there is no clinical evidence demonstrating that the benefits of screening outweigh the harms. However, smoking cessation discussions should still be taking place as a high priority.”

Smoking cessation efforts should remain a priority

As Huo pointed out, while lung cancer screening is important for reducing lung cancer mortality, smoking cessation should also be a huge focus for physicians. The urgency of this is highlighted by a recent study in JAMA Network Open, which showed that worldwide, it takes 52 individuals smoking for a mean of 24 years to kill one nonsmoker. The researchers calculated regional differences, with 86 smokers accounting for each death of a nonsmoker in North America, compared with 43 in the Middle East and North Africa, and concluded that these differences are likely a result of smoking bans that have been adopted in North America.

The AACR has always been an advocate for stringent tobacco control policies, which is why it commended the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for issuing a final rule requiring new health warnings on cigarette packages and in advertisements. “This is a major victory for public health as [health warnings] are an effective tool communicating the serious negative health consequences of cigarette smoking and tobacco use,” the organization said on Twitter.