Closing the Cancer Disparities Gap Broadened by COVID-19

As COVID-19 cases and death rates fall, and in-person activities resume, cancer centers once again fill their beds with patients receiving cutting-edge therapies. Although we have moved past the delays in cancer treatment experienced at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it may take years to understand the impact of this brief period of disruption on cancer incidence and mortality.

This is especially true for the communities that were hit hardest by the disease—often the same communities that experienced existing disparities before the pandemic.

At both the AACR Annual Meeting 2022, held April 8-13, and the 15th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held September 16-19, health disparities experts discussed the disproportionate difficulties that certain communities faced in terms of accessing cancer care during the pandemic—both within the U.S. and abroad. They also suggested important steps to combat cancer disparities in hopes of reversing some of the damage done by the disease.

Domestic Disparities in Pandemic-era Cancer Care

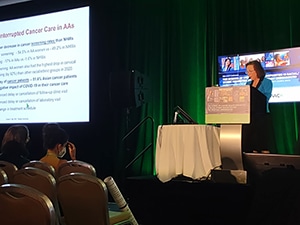

At the Annual Meeting, the minisymposium “COVID-19 and Cancer” showcased ways in which the pandemic impacted cancer care. In one talk, Jessica Islam, PhD, MPH, a professor of cancer epidemiology at the Moffitt Cancer Center, presented results from a study that evaluated differences in care and outcomes among cancer patients of different races and ethnicities, both with and without COVID-19.

Using data from the ASCO Survey on COVID-19 in Oncology—which recorded all COVID-19 cases in cancer patients at around 40 institutions between March 2020 and July 2021—Islam and colleagues found that 32 percent of non-Hispanic Asian patients and 29 percent of non-Hispanic Black patients required hospitalization for their COVID-19 diagnoses as compared with 23 percent of non-Hispanic white patients.

These disparities were also reflected in the receipt of cancer care during that timeframe. Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients were 18.9 percent and 11.4 percent more likely than non-Hispanic white patients, respectively, to experience a cancer treatment delay of two or more weeks. Similarly, 8.6 percent of non-Hispanic white patients had their treatment discontinued or canceled with no plans to restart, compared with 14.3 percent of non-Hispanic Black patients and 15.3 percent of non-Hispanic Asian patients.

The largest treatment disruptions, however, were observed among American Indian and Alaska native patients living in rural areas. Seventy-five percent of these patients experienced a treatment delay of two or more weeks, and 37.5 percent had care discontinued or canceled. Islam noted that while the sample size for this population was small, the results warrant further investigation and a concerted effort to overcome these disparities.

“The patient’s perspective should be brought to the forefront in order to understand how patient-provider communication may have played a role in these delays and discontinuations,” Islam said.

Since April, more data has emerged on ways the pandemic affected cancer care for different racial and ethnic groups. At the Disparities meeting, experts shared some of this updated data during a plenary session titled, “The Role of COVID in Worsening Existing Cancer Health Disparities in the U.S. and Globally.”

Amelie Ramirez, DPH, MPH, director of the Institute for Health Promotion Research and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences at UT Health San Antonio and associate director of Cancer Outreach and Engagement at Mays Cancer Center, discussed specific ways that the economic challenges of the pandemic had a lasting effect on the Hispanic community.

“There are a number of factors that go into the social determinants of health that impact the entire continuum of cancer health disparities,” she said. “Once COVID hit, this made it much more complicated to deal with some of the disparities we were seeing.”

She provided some sobering examples. During the pandemic, the number of Latinas in the workplace dropped by 2.74 percent between March 2020 and March 2021, compared with 1.7 percent for white women. Between 2019 and 2021, the number of Hispanics without health insurance increased from 20 to 30 percent, and between 2019 and 2020, childhood poverty increased by 4.1 percent.

Changes to health insurance coverage and financial stability likely contributed to the disproportionate treatment delays observed in Hispanic cancer patients, Ramirez said. In a population expected to experience a 142 percent increase in cancer incidence from 2010 to 2030, such delays could prove deadly. Ramirez also showed that for each month cancer treatment is delayed, the risk of mortality can increase by up to 10 percent.

Asian Americans also faced worsening social determinants of health, but in different ways, according to Grace Ma, PhD, associate dean of health disparities, director of the Center for Asian Health, and vice chair of the Department of Urban Health and Population Science at Temple University. Ma emphasized that an uptick in anti-Asian sentiment concurrent with the pandemic onset likely contributed to the treatment delays experienced by Asian American cancer patients.

Xenophobia related to the geographic origin of SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan, China) led to a significant increase in hate crimes perpetrated against Asian Americans—a rise of 164 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021, police data showed. Ma explained that the fear of violence and discrimination compounded the fear of contracting the virus, potentially causing more Asian Americans to avoid treatment centers.

Ma emphasized that other disparities in cancer care for Asian Americans may have been masked by the tendency to regard Asian Americans as a single epidemiological group. As an example, she pointed to the socioeconomic disparities between Asian Americans of different nationalities.

Because financial constraints significantly impeded the receipt of health care during the pandemic, Ma expressed concern that some Asian American groups also faced significant disparities in care. She explained that this information can be hard to find, however, as very few studies disaggregated their COVID-19 data to account for Asian American subgroups.

“Oftentimes, [the] model minority stereotype has masked the disparities in Asian American communities, as well as those who are struggling,” Ma said. “The aggregated data oftentimes paint a rosy picture of high socioeconomic status and low cancer burden, which has hindered the advancement of cancer research among the diverse Asian American populations.”

African Americans also faced individualized challenges in receiving cancer care during the pandemic, likely exacerbated by higher risks of developing severe cases of COVID-19, said Clara Hwang, MD, a medical oncologist at Henry Ford Health System. According to the AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care, African Americans were twice as likely as white individuals to die of COVID-19 and 2.5 to 3 times as likely to be hospitalized from the disease.

During spring of 2020, in the height of the pandemic, these disparities extended to cancer care, Hwang explained. Black patients with breast cancer, who already face higher mortality rates than their white counterparts, were 62 percent more likely to experience treatment delays than white patients. Similarly, Black patients with prostate cancer were over 30 times less likely than white patients to receive a prostatectomy, despite similar rates among the two races in 2019.

Vaccines designed to mitigate some of these disparities may not have helped as much as researchers hoped, Hwang continued, due to disparities in vaccine uptake. In addition to distrust of medicine, borne from historical injustices, early vaccine distribution was not always conducive to serving the most vulnerable populations. Sign-ups for the first two doses, for example, often required computer literacy and an internet connection.

“Who was able to sign up for these online appointments? People who were sitting in home in front of a computer,” Hwang said. “What about my 80-year-old patient with prostate cancer and on chemotherapy?

International Disparities in Pandemic-era Cancer Care

The widening of cancer care gaps is not exclusive to the United States, however. Muhammed Elhadi, MBBCh, a medical doctor at the University of Tripoli in Libya, presented a poster at the AACR Annual Meeting 2022 discussing how the 30-day survival of pediatric cancer patients differed between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries during the pandemic.

According to Elhadi, over 90 percent of pediatric cancer deaths occur in LMICs, often due to lack of access to diagnostics and treatment. To evaluate whether COVID-19 worsened these disparities, they collected pediatric cancer data from 91 hospitals worldwide, totaling 1,660 patients, between March and December 2020.

The researchers found that, after normalizing for age, sex, weight, tumor grade, and tumor stage, pediatric cancer patients in LMICs had a 35.7-fold higher risk of mortality than patients in high-income countries. Within the first 90 days of the study, 66 patients in LMICs had died, versus five patients in high-income countries.

At the Disparities meeting, Laura Fejerman, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences and co-director of the Women’s Cancer Care Program at the University of California Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, discussed how the social and economic structure of LMICs contributed to the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 in these areas.

While high-income countries issued sweeping lockdowns, transitioning many employees to remote work and supplementing unemployment checks for those who were laid off, LMICs did not have the infrastructure to implement such measures. The high prevalence of multigenerational households made quarantining difficult, and many health care providers did not have access to protective equipment.

A higher burden of COVID-19 required the reallocation of limited resources in nations like Peru, where Valentina Zavala, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California Davis, studied the effects of the pandemic on cancer care. Zavala partnered with researchers at the Peruvian National Institute of Cancer (INEN) and found that, when comparing rates of cancer treatment between the same months in 2019 and 2020, chemotherapy use decreased by half. Treatment of patients with radiotherapy decreased by 70 percent, and tumor-removing surgeries decreased by 90 percent.

“The previous presentations focused on minorities [and other] groups affected by COVID,” Fejerman said. “Imagine that, but now a whole country that’s almost [entirely] represented by poor individuals.”

Closing the Widened Gaps

As things return to normal, how can researchers rededicate themselves to pushing back against disparities the pandemic may have worsened?

Ramirez and Ma agreed that boosting diversity in clinical trials is an important step. In addition to removing bias and eliminating unnecessary exclusion criteria, both said that improving language support is crucial to improve enrollment of patients from underrepresented groups.

Ramirez directs an organization called Salud America! dedicated to curating and sharing research, tools, and stories about public health with the Hispanic community. One way the organization supports clinical trial inclusion is by raising awareness of clinical trials, and by sharing the stories of those who have participated.

Hwang said that researchers striving to minimize health disparities should form partnerships with such community organizations, as well as with policymakers and patient advocates who work in the health disparities space.

Zavala urged physicians to expand telemedicine options, offering phone calls instead of video visits to patients who may not have internet access. While telemedicine in Peru helped cancer patients receive prescriptions and undergo treatment monitoring during the pandemic, additional investments in infrastructure and disparities resources will be needed worldwide to allocate the proper resources to the people who need them.

Elhadi echoed Zavala’s call to action. “This pandemic has become the defining crisis of our generation, and its ramifications may stretch beyond the acute crisis and have far-reaching consequences for the future,” he said in a press release. “Our results underscore the need for a renewed assessment of health care resources.”

Recordings of all sessions from the Disparities meeting are available on demand to registered users until November 28. To register for on-demand access, please visit the registration page.