Are Ultraprocessed Foods Increasing Your Risk for Cancer?

Throughout human history, food has required some degree of processing to make it edible, improve its taste, or prepare it for storage. But with the Industrial Revolution came lifestyle changes and sophisticated technologies that demanded greater convenience and enabled a whole new level of food processing. The food industry was no longer limited to chopping, seasoning, and cooking whole foods. Now, industrially made ingredients could make food more appealing and increase shelf life, all while lowering costs. These advances led to the birth of what we know as “ultraprocessed foods.”

The socioeconomic benefits of ultraprocessed foods are hard to dispute. They’re cheap, quick to prepare, long-lasting, and easy to find—making nutritious foods like whole-grain bread accessible to many Americans who don’t have the time or resources to regularly bake a homemade loaf or to buy one from an artisanal bakery.

The popularity of ultraprocessed foods has continued to rise, and today, they account for nearly 60% of the American diet. Such high consumption, however, has many concerned that these foods could be wreaking havoc on our health.

But does the evidence support this concern?

Are all ultraprocessed foods equally harmful?

And what does “ultraprocessed” mean anyway?

Experts continue to debate these topics, weighing the strengths and limitations of past studies and finding improved ways to study and define this group of foods. The issue has even caught the attention of the federal government, which recently launched the Nutrition Regulatory Science Program to examine the health impacts of ultraprocessed foods and announced that it would develop a new definition of ultraprocessed foods—a step that could have ramifications for a slew of policies and dietary guidelines.

What Are Ultraprocessed Foods?

From peeled vegetables to potato chips, nearly everything we consume is processed—but clearly not to the same extent. To better study the health effects of differentially processed foods, in 2016, Carlos Monteiro, MD, PhD, from the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, and colleagues developed the now commonly used NOVA classification scale, which categorizes foods into one of four groups based on how processed they are.

Group 1 foods are those that are unprocessed or that have been minimally processed to remove inedible parts and/or to prepare the food for storage. Examples include fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables, meats, grains, eggs, nuts, and seeds.

Group 2 foods are ingredients used in cooking, such as butter, oil, sugar, vinegar, and salt, among others. Unlike Group 1 foods, these ingredients are not immediately found in nature. Instead, they are derived from Group 1 foods through processes such as churning, extraction, or fermentation. Butter, for example, is produced by churning milk, oils can be extracted from seeds, and vinegar can be produced from fermenting grapes.

Group 3 foods are processed foods produced by combining Group 1 and Group 2 ingredients and, in some cases, have been preserved via canning, bottling, or fermentation. Group 3 foods include sauteed vegetables, cheese, canned beans, and homemade bread.

Finally, Group 4 foods represent ultraprocessed foods, which are generated using ingredients and/or processes not found in a typical home kitchen, such as high-fructose corn syrup or hydrogenated oils. Because these foods are made with lower-quality ingredients, they often include flavorings, artificial colors, and other additives to improve their taste and appearance—things like butylated hydroxyanisole, xylitol, or red no. 40, to name just a few. Examples of Group 4 foods include soda, candy, most fast foods, breakfast cereal, chicken nuggets, lunch meat, packaged breads, plant-based milk, flavored yogurt, and meat substitutes.

How Do Ultraprocessed Foods Impact Health?

Using the NOVA scale, researchers have found correlations between ultraprocessed foods and a variety of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. As one example, a meta-analysis of 25 studies found that high intake of ultraprocessed foods was associated with an increased risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and high triglycerides. The degree to which the risks increased, however, varied widely between studies due to differences in how each was performed.

Building on this type of correlative data, a randomized trial conducted at the National Institutes of Health by Kevin D. Hall, PhD, and colleagues demonstrated that switching from a minimally processed diet to an ultraprocessed diet increased consumption and weight gain—lending credence to the notion that ultraprocessed foods are not just correlated with obesity but may in fact cause it.

But, as many experts have noted, it is still not known whether the effects are due to the ultraprocessing per se, or just a result of these foods often having higher levels of sugar, salt, and fat. And while some have suggested that ultraprocessed foods could be addictive, a separate study by Hall and colleagues disputed this theory, indicating that alternative factors could be to blame for the common overconsumption of these foods.

Do Ultraprocessed Foods Increase Cancer Risk?

Whether directly or indirectly, the idea that ultraprocessed foods are associated with increased risk of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases is well supported, but what about cancer?

Studies have shown associations between ultraprocessed foods and increased cancer risk, and a meta-analysis found that these foods were, on average, associated with a 12% increased risk of total cancer incidence. However, the association was considered “suggestive” and based on “very low quality” evidence.

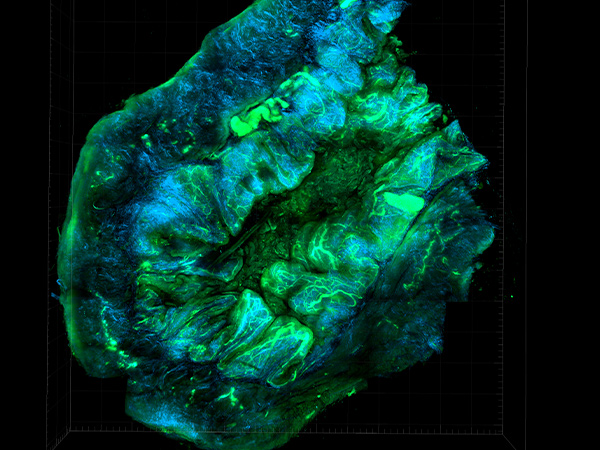

Among the individual cancer types examined in the meta-analysis, the researchers reported that only colorectal cancer was consistently associated with consumption of ultraprocessed foods.

As with other diseases, it remains to be seen whether it is the ultraprocessed nature of these foods that increases risk of cancer—for example, through additives or carcinogens derived from food processing methods—or whether the impact is primarily due to the higher levels of fat, salt, and sugar. These components could indirectly lead to cancer by promoting obesity, inflammation, and disruption of the gut microbiome or metabolic processes.

Substitution effects may also be at play, as eating a lot of ultraprocessed foods often means eating fewer of the unprocessed or minimally processed foods known to decrease cancer risk, such as fruits and vegetables.

Another important question is whether ultraprocessed foods as a whole are associated with cancer risk or whether the impact is driven by specific foods.

Interestingly, an analysis by Mingyang Song, ScD, from Harvard University, and colleagues found that high intake of ultraprocessed foods was associated with higher colorectal cancer risk for men but not for women. Song noted that the sex-specific impact could be due, in part, to differences in the types of foods men and women consumed.

“Ultraprocessed food is a very complex mixture of different food groups,” said Song during a presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2025, held this past April. “That makes the measurement and risk assessment particularly challenging.”

Certain ultraprocessed foods, including processed meat and sweetened beverages, have been convincingly associated with an increased risk of cancer, but most studies to date have not examined the impact of specific foods or individual ingredients and instead have treated ultraprocessed food as a monolith.

Much of this stems from the indiscriminate way that ultraprocessed foods are defined. Of note, the NOVA classification system is based solely on how processed a food is and does not account for a food’s nutritional value. As a result, foods like store-bought whole-grain breads—which provide fiber, complex carbohydrates, and other nutrients known to decrease cancer risk—are classified in the same category (Group 4) as soda—which has little to no nutritional value and is associated with liver cancer.

Experts argue that this feature of the NOVA system complicates interpreting the risks and benefits of ultraprocessed food consumption and may unfairly demonize otherwise nutritious foods.

“We believe that by considering both the food processing and nutrient profiles, we can better classify ultraprocessed foods,” Song said.

Should We Stop Eating Ultraprocessed Foods?

It’s still up for debate whether we should eliminate ultraprocessed foods from our diets. Some experts recommend limiting their consumption, pointing to the many studies linking these foods to poor health outcomes. Others argue that there isn’t convincing evidence yet to show that ultraprocessing itself, rather than individual ingredients commonly found in these foods, is inherently harmful.

Regardless of their views on ultraprocessing, experts agree on the importance of prioritizing nutritious foods and limiting those high in sugar, salt, and fat, which are linked to many diseases, including cancer.

Experts also agree on the need for more research.

To tease apart the contribution of specific ultraprocessed foods and ingredients on disease risk, researchers need to develop a more nuanced definition of ultraprocessed food that incorporates nutrient profiles, Song said.

In addition, identifying biomarkers of ultraprocessed food consumption and following large cohorts over many years will help researchers better understand the impact on cancer, and studies that examine how dietary changes and other interventions impact cancer risk will be required to demonstrate causality.

Acknowledging some of the lifestyle benefits of ultraprocessed foods, Song noted, “I don’t think it’s realistic for us to eliminate ultraprocessed foods from our diet.”

However, he hopes that “further research to improve the assessment of ultraprocessed foods and identify specific ingredients in ultraprocessed foods that may increase cancer risk … will inform future regulatory and policy changes.”