Skipping the Scalpel: Can Some Patients Avoid Surgery, Preserve Their Organs, and Still Beat Cancer?

For many people, the word “cancer” immediately calls to mind surgery—the removal of a tumor, a breast, part of the digestive tract, or even an entire organ. For more than a century, surgery has been one of the most reliable ways to control cancer, and it remains so today. Yet patients and doctors have long recognized the profound physical and emotional costs of losing parts of oneself. Organ loss can alter appearance, daily function, fertility, sexuality, and sense of identity.

In recent years, an emerging movement within oncology has been asking a radical question: Can we treat cancer effectively by avoiding or limiting surgery to preserve the organs that make us who we are?

No disease illustrates this tension more vividly than breast cancer. Here, the full spectrum of choices is most evident, ranging from preventive surgeries such as double mastectomy for women with BRCA mutations, to breast-conserving lumpectomies, to trials exploring whether certain early cancers might be treated and then safely monitored without surgery at all. Compared with endometrial or ovarian cancer, where prevention has often meant the complete removal of reproductive organs, breast cancer has seen steady clinical progress toward “right-sizing” approaches for patients. As a result, breast cancer serves as a proving ground for many of the concepts that define modern organ preservation.

Recent studies are redefining how much surgery is truly necessary in breast cancer. For women with low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), the COMET trial reported that active monitoring was not inferior to immediate surgery plus radiation for short-term invasive cancer risk. Furthermore, a COMET companion analysis highlighted the positive finding that quality of life, anxiety, and depression were comparable in both groups, suggesting that surgery may not always add measurable benefit in the early years after diagnosis. (For a deeper dive into the expanding options for patients with DCIS, read our blog post.)

Beyond the numbers, the personal reality is often simpler and more profound. As patient advocate Stacey Tinianov acknowledged, “Sometimes individuals feel better if the organ that has developed a tumor is completely gone, and that’s okay.”

In invasive disease, one trial tested the omission of breast surgery in patients with a complete pathologic response after neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Treated with radiation alone, all of these women remained alive and recurrence-free after more than four years of follow-up.

The role of the lymph nodes in breast cancer care is also being reconsidered, with the INSEMA trial showing that in women with node-negative early breast cancer, omitting axillary surgery did not compromise invasive disease-free survival and resulted in less lymphedema, pain, and impaired arm mobility.

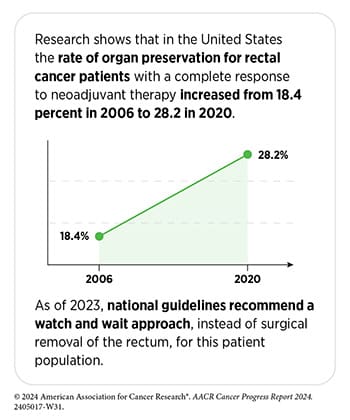

Rectal Cancer: When “Watch and Wait” Works

Rectal cancer may represent the most promising model of organ preservation in practice. Traditionally, removing the rectum often meant a permanent colostomy bag, a profound change to daily life. But over the past decade, oncologists have investigated new ways to spare some patients from this outcome. By delivering chemotherapy and radiation before surgery, doctors have long been able to shrink rectal tumors so dramatically in some patients that the cancer effectively disappears. For patients who experience these complete responses, the rectum can sometimes be left in place under a careful “watch and wait” approach, sparing patients the life-altering consequences of rectal surgery.

More recently, immunotherapy has added a striking new chapter to this story. In a small but closely watched trial highlighted during the AACR Annual Meeting 2025, patients with mismatch repair-deficient (MMRd) rectal cancer were treated with immunotherapy alone, and all experienced complete responses without the need for surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation. Impressively, 96% of patients were still disease-free two years later. While these results are still early and apply only to a subset of cancer patients, they hint at a future where rectal cancers might be cured without removing the rectum at all. (This trial also included patients with MMRd non-rectal cancers, including gastroesophageal, hepatobiliary, genitourinary, and gynecologic tumors. Here, 65% of these patients experienced complete responses to immunotherapy alone, and 85% of those patients remained recurrence-free at least two years later.)

Head and Neck Cancers: Saving Face(s) to Preserve Appearance and Identity

Cancers of the face, jaw, and sinuses carry some of the most visible and life-altering consequences of surgery. Traditional operations may require orbital exenterations that remove an eye and maxillectomies or mandibulectomies that remove the upper and lower jaw, respectively—procedures that can permanently change how a person looks, speaks, or eats.

Recent studies show that induction or neoadjuvant therapies can reduce the need for these disfiguring operations. Results from a phase II trial published in the AACR journal Clinical Cancer Research revealed that in patients with advanced sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma who received induction chemotherapy, 82% experienced responses.

Furthermore, among those alive at two years, 63% of the cancer patients were able to avoid major surgeries such as orbital exenteration or craniofacial resection. Similarly, another trial, also published in Clinical Cancer Research, enabled structural preservation of the face in 71% of patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with just 18% of patients treated with surgery alone.

For rare jaw tumors like ameloblastoma, precision medicine is also expanding options for patients. In patients with BRAF-mutated ameloblastoma, targeted therapies against BRAF shrank tumors sufficiently to convert planned radical resections into mandible-preserving surgeries in over 90% of cases.

Together, these findings demonstrate how advances in systemic therapy are shifting the goals of treatment in head and neck cancers: from not only extending survival but also preserving the structures that define appearance, speech, and social identity.

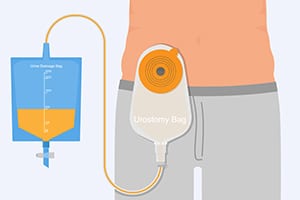

Bladder Cancer: Moving Beyond Cystectomies

Radical cystectomy, which involves removal of the entire bladder and sometimes other nearby tissues, has long been the standard for muscle-invasive bladder cancer, but it is life-altering. One newer strategy may offer a viable alternative for some patients.

This three-pronged therapeutic approach begins with transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), a minimally invasive surgery that removes the tumor through the urethra while leaving the bladder intact, followed by radiotherapy plus concurrent chemotherapy. Promisingly, a trial showed that chemoradiation therapy significantly improved locoregional control and lowered cystectomy rates, with long-term follow-up confirming durable benefits and no drop in quality of life.

Replacing chemotherapy with dual immune checkpoint blockade has also demonstrated promise, according to the phase II IMMUNOPRESERVE trial, whose results were published in Clinical Cancer Research. After TURBT, patients received both PD-1 and CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibitors along with radiotherapy, and more than 80% of patients experienced complete responses. Nearly two-thirds of patients were alive and disease-free with intact bladders at two years, and 84% of patients were alive after 10 years, with most maintaining normal bladder function.

The Road Ahead

Taken together, these recent data reveal a profound shift in oncology. Organ preservation is no longer a distant dream but a growing goal, supported by evidence accumulating across cancer types. Yet important questions remain. Which cancer patients can safely avoid surgery? How accurately can we determine whether one’s cancer has been totally eliminated? How do organ preservation approaches affect recurrence risk over an individual’s lifetime, and how should patient preferences guide these decisions? Answering these questions will require more trials, more patient-reported outcomes, and more long-term follow-up. But the trajectory is clear: The days of automatically removing entire organs are fading, replaced by a new ethic of tailoring treatment to each patient’s biology, needs, and values.