From the Bench: Finding New Ways to Detect Cancer Early

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, but when caught early, many cancers can be treated and kept at bay. Screening methods like colonoscopy, mammography, and Pap tests have been critical to boosting the early detection of colorectal, breast, and cervical cancers, respectively, but most cancers do not have screening tools available. As a result, malignancies such as pancreatic, stomach, and ovarian cancers are typically caught late when the prognosis is poor.

Some of the challenges facing early cancer detection include nonspecific symptoms that are often mistaken for other conditions and the inaccessibility of internal organs, which prevents patients and physicians from easily feeling or imaging tumors. Researchers are striving to find new approaches to enable early detection of more cancers, with the ultimate hope of helping patients live longer.

In this installment of From the Bench, our quarterly series featuring creative approaches to cancer research, we’ll examine innovative early detection strategies under exploration—including microscopic cancer hunters, platelets that sop up DNA, voice as a biomarker, and electronic noses that sniff out cancer.

Blood Will Tell: Creative Ways to Improve Blood-based Liquid Biopsy

One promising early detection approach is blood-based liquid biopsy, which looks for signs of cancer in the blood and could supplement, and one day even be an alternative to, traditional tissue biopsy. The premise is that tumors release cells and DNA into the bloodstream, so tests that look for these circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood samples may help find cancer earlier and more easily than traditional methods.

Blood, however, consists mostly of noncancerous cells and molecules shed from normal cells, so liquid biopsy requires enrichment methods to isolate and identify the minority of cells and DNA coming from malignant tumors. Methods like DNA mutation-specific probes, DNA methylation immunoprecipitation, cell surface marker immunoprecipitation, and others are commonly used for this purpose, but each comes with its own limitations, so researchers are continuing to explore alternatives to improve the enrichment of ctDNA and CTCs.

Hunting for Signs of Cancer

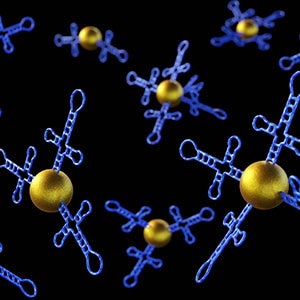

As one example, recently reported in Advanced Science, researchers have developed a self-propelled “hunter” to track down and capture CTCs found within blood samples. The authors of the study explain that frequently used immunoprecipitation methods, which isolate CTCs by using an antibody against the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) protein commonly found on the surface of cancer cells, require separation of the antibody-protein complex at the end of the procedure. This forcible separation can destroy the integrity of the captured cells and preclude further analysis, they noted.

In contrast, their method captures CTCs with a three-dimensional DNA structure designed to bind to EpCAM. The DNA structure (known as an aptamer) is easily degraded at the end of the procedure without harming the integrity of the captured CTCs. And unlike prior aptamer-based approaches that relied on passive diffusion to bring CTCs into contact with the aptamers, their design pairs the aptamers with a self-propelled motor that drives them to the CTCs.

The new system, which the authors describe as a magnetic micromotor-functionalized DNA-array (MMDA) hunter, combined an EpCAM-targeted aptamer, iron-containing nanoparticles, and the enzymes glucose oxidase and catalase. These components were held together with various DNA structures and streptavidin-biotin interactions.

The structure’s glucose oxidase converts glucose from the blood into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide, and catalase then converts hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. The oxygen bubbles produced by these reactions propel each MMDA hunter through the blood sample, increasing the chances that the EpCAM-targeted aptamer will encounter and bind to CTCs. The iron-containing nanoparticles endow the MMDA hunter with magnetism and allow for isolation of the MMDA hunter and bound CTCs using a magnet.

The researchers demonstrated that the MMDA hunter was able to capture more than twice the number of CTCs from clinical blood samples compared with prior approaches that relied on passive diffusion. Moreover, the number of CTCs isolated from patients with cancer was significantly higher than that isolated from healthy patients, highlighting the potential of a MMDA hunter-based liquid biopsy approach to accurately identify patients with cancer.

Platelet-based Liquid Biopsy

To improve the enrichment of ctDNA, a team of researchers is turning to platelets, blood cells that are often discarded when blood is processed for liquid biopsy. As reported in Science, platelets were found to act like DNA sponges, internalizing free-floating DNA from the blood. The researchers behind the study hypothesized that since platelets can sense and absorb genetic material from viruses as part of the body’s defense against infection, they may also be able to absorb circulating genetic material that comes from the body’s own cells.

By analyzing purified platelet samples, the researchers confirmed that platelets contained human genomic DNA, including fetal DNA in pregnant individuals and ctDNA in patients with cancer. Genomic DNA was found in the majority of platelets analyzed and at higher levels than in the platelet-depleted plasma typically used for liquid biopsy.

Further, the ctDNA molecules taken up by platelets maintained their histones and histone modifications—enabling similar types of analyses as conducted on ctDNA isolated from plasma—and had the same copy number alterations and mutations found in plasma-derived ctDNA. In addition, ctDNA could even be detected in platelets from patients with cancers that shed low levels of ctDNA.

Based on their findings, the authors suggested that conventional liquid biopsy approaches that use platelet-depleted plasma are missing out on a wealth of ctDNA molecules housed within platelets. Incorporating platelet-derived ctDNA into liquid biopsies could, therefore, enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of blood-based early cancer detection.

Thinking Outside the Vein: Alternatives to Blood-based Cancer Detection

Researchers are also exploring using other bodily fluids, including urine and breast milk, to test for cancer and are even looking beyond fluids—with new data highlighting how changes to our voices or breath could signify cancer.

Can You Hear Cancer?

In an article published in Frontiers Digital Health, researchers explored the role of voice as a cancer biomarker, reasoning that tumors arising in the vocal folds may induce detectable changes to the voice. They analyzed voice recordings from individuals who had laryngeal cancer, benign focal fold lesions, or no vocal fold disorders to identify the acoustic features that were most different among these groups.

The analysis revealed that the harmonic-to-noise ratio (the ratio of regular pitch patterns to irregular patterns that are considered noise) and fundamental frequency (how often the vocal cords vibrate, which influences pitch) were significantly different in individuals with laryngeal cancer compared with those with either benign vocal fold lesions or no vocal fold disorders. When the analyses were conducted based on sex, these differences, however, were found among men, but not women. The results suggest that, with further research, changes to certain vocal features could someday help identify laryngeal cancer.

The Nose Knows Lung Cancer

And while we are holding our breath for the next big leap in cancer detection, new research suggests that exhaling that breath may be one promising direction. Cancer has long been known to produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and researchers have explored the potential of animals, such as dogs or locusts, to detect these cancer-related VOCs. In a study published in Annals of Oncology, researchers reported the real-world efficacy of an alternative sniff test: an “electronic nose” that analyzes exhaled breath.

An electronic nose (eNose) uses sensors to detect specific groups of VOCs in exhaled breath, applies pattern recognition algorithms to generate a breath profile based on the unique VOC mixtures found in each sample, and calculates the probability that a particular condition—for example, cancer—is present.

In this multicenter prospective validation study, researchers developed and tested the efficacy of a new eNose model designed to determine the probability that a patient has lung cancer. The trial included 364 participants suspected of having lung cancer based on clinical or radiographic signs. They found that eNose identified lung cancer with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 63%. The ability of eNose to detect lung cancer was consistent across centers and across tumors of different stages and features.

The authors propose their new eNose model as a reliable and noninvasive method to detect lung cancer in individuals with signs of the disease. They suggest that screening with eNose could spare the majority of patients with benign conditions from invasive diagnostic tests.

From technical advances that may improve the development of early detection tests all the way to tests that are already showing efficacy in real-world patients, these studies highlight the many creative approaches researchers are undertaking to make early detection a reality for more cancer types.

To learn about even more advances in early detection, check out these AACR resources: