Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment Advances in 2026

Cancer researchers are approaching 2026 with a renewed focus on early detection and prevention, personalizing treatment, and closing gaps in care. Leading voices across oncology point to advances already taking shape—strategies to prevent and intercept cancer before it becomes life-threatening, precision tools that refine therapy choices, immunotherapies designed for hard-to-treat tumors, artificial intelligence accelerating discovery and diagnosis, and initiatives aimed at reducing disparities. We spoke with experts in these fields, to understand how these developments together signal an upcoming year where scientific breakthroughs and implementation converge to reshape the trajectory of cancer care and research:

- Cancer Prevention, Detection, and Interception – AACR Chief Scientific Advisor William Hait, MD, PhD, FAACR;

- Precision Oncology and Drug Development – AACR President-Elect, 2025-2026 and Director of Clinical Cancer Research at the Mass General Cancer Center Keith Flaherty, MD, FAACR;

- Cancer Immunotherapy – Director of Immunotherapy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Nina Bhardwaj, MD, PhD, FAACR;

- Artificial Intelligence in Cancer – Chair of the Computational and Systems Biology Program at the Sloan Kettering Institute Dana Pe’er, PhD, FAACR; and

- Cancer and Health Disparities – Chief Medical Officer of PanOncology Trials Marcia Cruz‑Correa, MD, PhD.

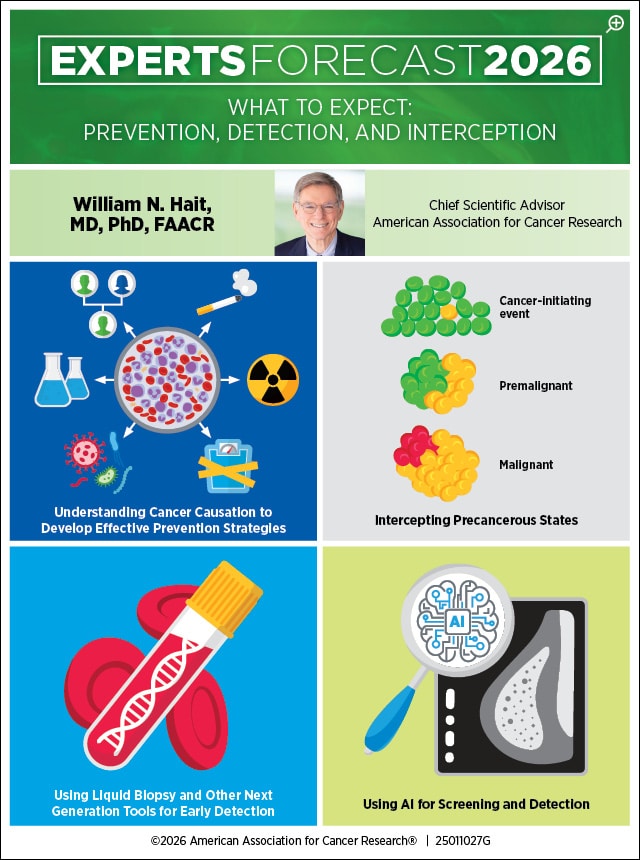

Advances in Cancer Prevention, Detection, and Interception in 2026

One question that Hait, former global head of Janssen Research and Development and AACR Chief Scientific Advisor, had heard many times from his cancer patients in his 30 years of practicing medical oncology before his tenure in industry was, “I didn’t smoke, I didn’t drink, no one in my family has cancer. What could I have done to prevent this?” That simple yet profound question sets the tone for his forecast: In 2026, the field needs to move upstream—toward understanding causation, studying interception, and sharpening early detection—while policy begins to reward prevention.

Until we shift our focus to a much greater extent in preventing cancer, the incidence of cancer won’t change, said Hait. He framed prevention as a direct translation of causation research: “To prevent a disease, we have to know what causes it, and the translation of that research would be into not treatments as we know them today—treatment of established disease—but treatment of a risk, to reduce the risk.”

Hait noted that this is more than semantics—it is the idea that measurable biological transitions long before overt cancer occurs can and should be treated. Interception, in Hait’s view, is already beginning, and it will expand. He pointed to treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast as well as intercepting multiple myeloma, a form of cancer that begins in the plasma cells (a type of white blood cells), as the clearest examples: “In myeloma, we have identified a premalignant state called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) which could progress to smoldering myeloma and eventually multiple myeloma,” he said. “We now have approved drugs for the treatment of smoldering myeloma to intercept the process before you are ever diagnosed with the fatal form.”

Hait underscored how that progress took 15 years, referencing work he helped launch while at Johnson & Johnson and the recent regulatory milestone. “In November this year, we were able to get daratumumab (Darzalex) approved for high‑risk smoldering myeloma,” he noted. For 2026, Hait expects similar logic to expand to other premalignant conditions such as Barrett esophagus, prostate intraepithelial neoplasia, and clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), which are known to cause higher risks of esophageal, prostate, and blood cancers, respectively.

Early detection is improving, said Hait. Lung cancer screening with low‑dose computed tomography (CT)—a procedure that uses relatively lower dose of radiation to take a series of X-rays of the body—has saved lives, but initially, such efforts were stuck, because of limited access and difficulties in determining which lung nodules seen on the scan would need medical attention, he explained. Hait sees the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in radiomics—using data science to extract quantitative features from clinical images like scans or slides—as a practical way to discriminate which of these pulmonary nodules in a scan could be problematic, thereby reducing false positives and unnecessary procedures.

On blood‑based tests, his message was pragmatic: “Liquid biopsies will improve with time, the more data that we generate, the more that we can apply machine learning to understand which signal is really a serious signal, not a false positive.” He cautioned that localization, which is finding the source of where the tumor cells in the blood are originating, remains a hurdle in some contexts, and researchers need to pair blood signals with intelligent, minimally invasive localization strategies.

“We need more serious effort to credential surrogate endpoints in earlier disease, such as biomarker responses and circulating tumor DNA assessments, so trials can act on reliable predictors rather than waiting for overall survival where it is impractical,” said Hait. “A hundred years from now, they’re going to look back at us and say, could you believe our ancestors used to wait until they got a disease before they did anything about it?” he quipped, going on to explain how future generations might judge our current approach as inefficient and detrimental.

For 2026, Hait’s prescription is clear: fund causation, normalize interception, deploy smarter early detection with radiomics and blood‑based tools, and build systems that favor preventing catastrophic disease. “It doesn’t happen by wishing that it will happen,” he said. It happens by deciding—at the lab bench, at the bedside, and in the policies that govern both—to act earlier.

Advances in Precision Oncology and Drug Development in 2026

Flaherty sees 2026 as a year where novel chemistry meets earlier care, guided by multimodal precision models that move beyond DNA‑only thinking.

“I’m most excited about the novel chemistry advances that will help with early interception of cancer,” he said. Fundamental advances will yield molecules that are better suited for smart approaches, explained Flaherty. Classes of molecules like chemical inducers of proximity (CIPs) can be used in novel strategies to address targets, he said. CIPs, such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), bispecifics, and molecular glues, alter how proteins interact and function by bringing two or more biomolecules into close spatial proximity to selectively modulate protein function rather than merely blocking or degrading them, said Flaherty.

His predictions align with much of what was presented at the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets held in October 2025—PROTACs for tackling KRAS G12D-mutated pancreatic cancers and a bispecific antibody for treating certain advanced gastroesophageal cancers, to name a few. “I wouldn’t expect much clinical data in 2026, but I am confident that we will see the groundwork for medicines based on molecules like this, with studies on their design feasibility, gathering robust preclinical data, and other such steps that will eventually lead to clinical studies,” said Flaherty.

Precision oncology, in Flaherty’s telling, is maturing into a multimodal discipline. “For the longest time when we’ve thought about precision oncology, we’ve really referred to DNA sequencing, first and foremost, but there are other molecular analytes in cancer cells that clearly have import,” he said. RNA sequencing, proteomic platforms, and, crucially, digital pathology augmented with multiplex immunofluorescence will see some growth, said Flaherty. “We can actually process digital pathology image data to probe specific protein components and use it to cast a much broader net to improve how we characterize or phenotype cancers,” he explained.

Multimodal models that integrate routine clinical data and radiographic data, in addition to molecular information are highly capable of identifying unmet needs in cancer populations, Flaherty explained. The models can be designed to match those identified needs to therapies that are both available and investigational—with more precision than single mutations allow, he added. “This broader phenotyping could subdivide traditionally monolithic diseases like pancreatic cancer, primary brain tumors, particularly glioblastoma and sarcomas into actionable niches,” he noted.

Flaherty expects earlier deployment of therapies to be the most immediate and visible change. For years, clinicians have struggled to tell who still has microscopic cancer after surgery and who is truly in the clear, said Flaherty. “Our ability as clinicians, to detect microscopic residual disease (MRD) is growing, helping us better identify which patients truly need adjuvant treatment and to spare those who don’t from unnecessary side effects,” he added.

He emphasized circulating tumor DNA as a leading tool and sketched a novel paradigm of deploying multiple lines of therapy in patients who haven’t had radiographic or clinical recurrence, but whose blood‑based assays showed that their cancer would recur. In 2026, Flaherty expects more trials to customize adjuvant therapy based on MRD signals—switching agents, escalating intensity, or adding novel therapies—rather than waiting for a scan to confirm what the molecular markers already foretell.

The regulatory conversation will evolve alongside these shifts. At present, overall survival is the gold standard, and it will remain so, especially in aggressive cancers, he said. However, many U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals have relied on progression‑free survival in recent years, he continued. Flaherty anticipates an active hunt for novel surrogate markers, including biomarker responses from blood‑based technologies, that can be credentialed as reliable predictors.

Finally, Flaherty flagged a tangible signpost in pancreatic cancer to anticipate in 2026—RAS inhibitors other than those targeting KRAS G12C that are emerging but not yet leading to FDA approval. Even if big approvals do not land in 2026, he expects evidence to accumulate and multimodal phenotyping to reveal which subsets can benefit earlier than traditional organ‑based treatment categories would predict.

Taken together, Flaherty’s 2026 is about rationality—better molecules aimed at targets previously considered off‑limits, better models that describe a tumor’s phenotype and microenvironment, and earlier clinical decisions informed by MRD. In Flaherty’s words, “combining those approaches with early-detection methodology is going to be the ultimate game changer.”

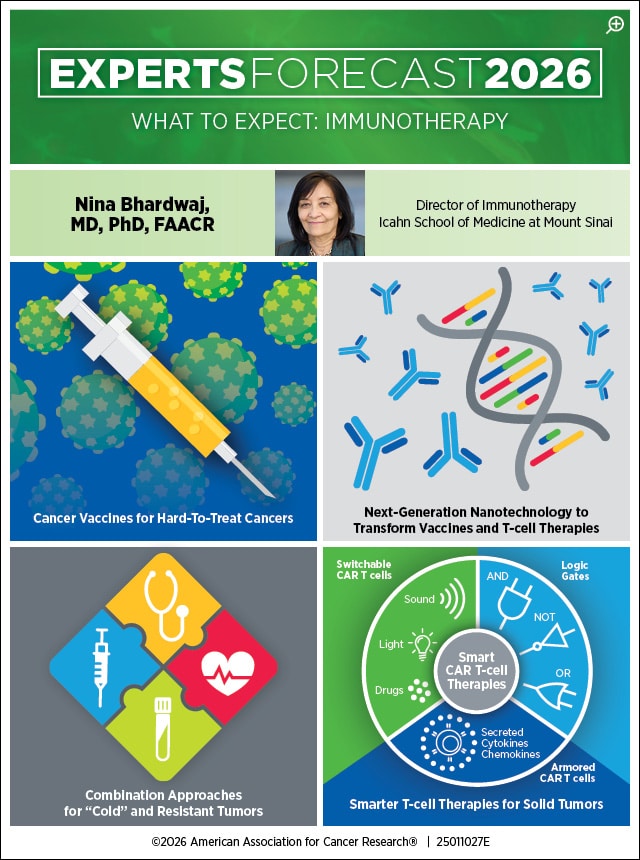

Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy in 2026

For Bhardwaj, the story of 2026 in immunotherapy is one of engineering: smarter cell therapies that can function in hostile tissues, vaccines built on a broader antigen universe and delivered with more sophisticated platforms, and combinations that reshape the microenvironment of traditionally “cold” tumors.

She began with cell therapies, explaining how the frontier is evolving from raw potency to intelligent persistence. “Over 2026 we would see continued advancements in cellular therapies—T-cell therapies, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapies, T-cell receptor (TCR) transduced T cells, and smart T‑cell therapies that are armored, both ex vivo and in vivo.” Bhardwaj describes advancements with T cells as a broad future direction, with multiple cutting-edge strategies being explored in the field.

For instance, armored T cells are next-generation T cells that are modified to express their own cytokines and chemokines, helping them to proliferate and persist in tumor microenvironments (TMEs) better than their nonarmored counterparts. “We’ve seen real progress in delivering T cells armored with IL‑18 in lymphoma, and there are also studies that work with IL‑12, IL‑15, even IL‑7,” Bhardwaj said. This avenue of research was also examined in early 2025 at the AACR Immuno-Oncology Conference (AACR IO), where multiple strategies to modifying CAR T cells were discussed. Bhardwaj is the scientific committee cochair of AACR IO 2026, where there will be more studies presented on this topic.

Other T-cell advancements, such as the ones in recent studies published in Cancer Discovery detail approaches to tune CAR T-cell recognition and enhance potency through modular designs that incorporate synthetic receptors, switchable signaling domains, and payload delivery systems. These innovations aim to overcome the challenges Bhardwaj emphasized: immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments, trafficking barriers, and functional exhaustion. By integrating cytokine expression with logic-gated circuits and nanotechnology-based in vivo engineering, researchers are building T cells that not only attack tumors but adapt dynamically—mirroring the vision Bhardwaj outlined for 2026.

“With the advent of sophisticated nanotechnological approaches, we will be able to dramatically enhance the efficiency of not just cell therapies, but other approaches like RNA vaccines and drug delivery agents as well,” Bhardwaj explained.

In addition to seeing a boost in efficiency for vaccines, we will see an expansion of what they target and how they arrive, said Bhardwaj. “We started out with tumor‑associated antigens, tumor‑specific antigens, and neoantigens based on single nucleotide variants,” she said. “We’re realizing that there really is a wealth of tumor‑associated, tumor‑specific antigens that we’re continuing to discover, including those from alternate reading frames, alternatively spliced RNAs, and formally untranslated regions that could produce dark matter antigens,” she continued. That expansion supports both “personalized” approaches—built around what an individual tumor expresses, as well as off‑the‑shelf types of antigens that are being applied in the clinic. On delivery, she expects—and has already seen—RNA vaccine platforms that are successful in the infectious disease field being carried over with encouraging results in melanoma, and lipoplex platforms in pancreatic cancer.

She emphasized that these platforms can be further enhanced substantially to include not just antigens, but other molecules that are often used in immuno-oncology, including maturation agents and immune modulators, copackaged for tissue‑targeted release.

Bhardwaj offered several examples of how such advancements would affect specific types of cancer treatments. For uveal melanomas, which, according to Bhardwaj, are notoriously hard to treat, she pointed to TCR approaches targeting gp100 and CD3 and the approval of tebentafusp (Kimmtrak). In synovial sarcomas, which are a rare type of cancer that form in the body’s connective tissues, she highlighted approvals with TCR‑directed therapies. In pancreatic cancer, she described RNA lipoplex vaccines in combination with chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy to have much potential.

“Prostate cancers are traditionally harder to treat with immuno-oncology, but we see encouraging data with B7H3‑targeted approaches,” she added. A 2024 study published in Cancer Research Communications dives further into this, outlining an investigation of B7H3 as a potential target in a pan-cancer dataset aggregated by the Caris Precision Oncology Alliance consortium.

These leaps in advances are not surprises, Bhardwaj said, rather these have been years in the making, driven by practical innovations, and sometimes used in combinations to yield greater effect. “It’s all very exciting, we are seeing approaches that are not just unilateral, but multipronged, and tailored to the biology at hand.”

Advances in Artificial Intelligence in Cancer for 2026

Pe’er’s view of AI is both expansive and grounded: expansive in what technology can now accomplish; grounded in how it should be used—with clinicians in the loop and equal access at the forefront. In 2026, she expects AI to continue to transform drug design, accelerate trial matching, and translate clinical imaging data into actionable patterns, and augment drug repurposing across cancers guided by shared microenvironmental “languages.”

“AI is going to be very transformative, and it’s going to do a lot, all over the place, and all at once,” she said at the outset. On drug design, Pe’er tied today’s capabilities to the cascade that followed breakthroughs in protein structure prediction: “The 2024 Nobel Prize that was awarded for AI in understanding protein structure has led to AI being used in the process of designing molecules.” Now most pharmaceutical companies use this approach, building these computational protein science labs into their process loop, said Pe’er. The practical consequence is that the process of designing a new molecule is combinatorial and faster—resulting in molecules that are much more sophisticated and accurate. In 2026, she expects this “lab‑in‑the‑loop” model to continue supercharging discovery pipelines across startups and big pharma alike.

Pe’er then digs into another vital aspect of research—trial matching: “We’re only going to move forward if we can have clinical trials, and the number of factors that matter for these clinical trials is too much for any given doctor to hold all this in their mind,” she said. AI systems can rapidly cycle through information, by indexing thousands of clinical trials, navigating a torrent of eligibility criteria and updates, and matching them to appropriate patients. The result is more patients in clinical trial studies for therapies that need testing.

Pe’er’s prediction for the most electric near‑term shift is in pathology. “AI models built for digital image processing are able to read clinical slides much better than a human,” she said. “Our minds have not evolved to look at these histopathological image slides which consist of billions of pixels—AI is really good at finding new patterns and reason at multiple scales, making it perfect for this use case,” said Pe’er. A recent study, presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2025 is a good example. An AI model built using clinical data paired with tissue slide images and genetic data outperformed an existing breast cancer risk scoring test when it came to predicting five-year recurrence risk.

This technology will not replace pathologists, it will augment them—it helps pathologists to open the door to drug repurposing by seeing architectures and ecologies that recur across cancers, noted Pe’er. Radiology, she added, is also taking the same path, right behind pathology in terms of this technological development.

Pe’er anticipates a great deal of cross-functional research being accelerated through AI. “Cancer is siloed,” she noted, “lung cancer, thyroid cancer, pancreas cancer—and even within those, subtyped by their mutation, and there’s a lot of shared components that we can uncover across cancers, cancer types, tissues, and metastatic sites.” That shared language—revealed by AI reading slides and multimodal features—can break the barrier and identify, for instance, a drug that works so amazingly in lung cancer, might also help this particular patient with gastric cancer, based on pattern match rather than organ label, said Pe’er.

“What’s holding us back is limited funding—there isn’t enough for academic labs to be able to do this, and there is an industry misalignment, because for repurposing to be truly powerful, it has to work across multiple drugs, and multiple cancers,” said Pe’er, discussing the logistics involving leveraging AI in this manner. In her view, academic labs, provided with the necessary resources, can do this agnostically.

Pe’er further addressed other concerns about AI, speaking about privacy and data ethics when implementing AI solutions to obtain cancer therapy insights. “The data from our emails, Google searches, phone locations, and ‘ChatGPT conversations’ already change hands multiple times,” she explained. It is vital to argue for safe, transparent, and responsible data use in the context of health privacy, but at the same time, have a good framework where pooled health data can help entire communities in the most effective way, she pointed out.

Finally, Pe’er went over the role of clinicians: “AI needs to be used synergistically, augmenting the doctor rather than replacing the doctor.” AI models are good when things are common and typical, but aren’t as good with messy complexities, as the outliers, where the experience of the doctor matters most, explained Pe’er.

Overall, Pe’er’s vision of the future focuses on drugs designed faster, more patients reaching trials that fit, pathologists and oncologists discovering tumor ecologies by reading tissue slides and imaging data, and early cracks in the organ‑silo paradigm via AI.

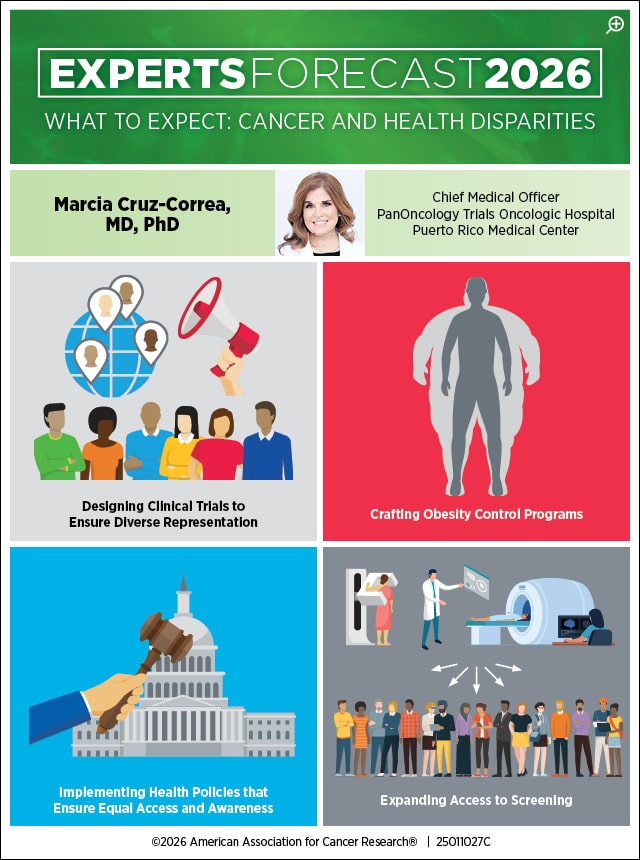

Advances in Cancer and Health Disparities for 2026

Cruz‑Correa’s forecast drives home the heart of the matter for advances in cancer—the best science matters only if people can reach it. In 2026, she expects tangible progress on the front door of care—screening uptake, portable precision oncology, community trials—and a fuller embrace of metabolic health as part of cancer prevention and survivorship, not an afterthought.

Cruz-Correa started with colorectal cancer screening, where colonoscopy’s success has long lived alongside access barriers. “For years, we’ve had colonoscopy‑based methods for colorectal cancer screening, but people from minorities, vulnerable populations, and those that have less access to GI doctors, don’t seem to be getting screened,” she said. Her expectation for the coming year is more widespread adoption of newer, less invasive screening methods, such as stool‑based and blood‑based tests, with the hope that such tests will be more accessible and be covered by insurance. In her clinical practice, she explains that her group at PanOncology in Puerto Rico is already participating in a clinical trial to test the diagnostic accuracy of such tests, with the goal that some of them will be already approved for 2026.

Cruz-Correa then turned to lung cancer. “We have identified that about 5%, and in some places 10%, of patients that should have undergone early detection and screening, but did not receive it,” she said. Innovative solutions on how to make screening available to such patient populations exist, explained Cruz-Correa, describing how mobile, low-dose CT scanning equipment were fitted on to buses, enabling a mobile screening facility to reach communities with reduced access. Like Hait, Cruz-Correa explained how policy efforts and health insurance coverage must align to make screening straightforward. “Early-stage cancer is curable, and every barrier we remove translates to lives saved,” she said.

Cruz‑Correa broke down the core concept of disparities—arming patients and clinicians with the information they need. We need germline genetic testing to be more widely adopted, she said. Once we know about the patients’ genetics, they can be guided to better options, and importantly, be provided access to those new and evolving technologies, she continued. Initiatives to make drugs available locally, tele‑oncology connections, or intentional opening of trials within community networks, are all viable options, said Cruz-Correa.

“Only about 5%—some new studies say maybe 7%—of all patients with cancer have the availability to participate in clinical trials,” she said, speaking further about trial access.

The consequence is a development pipeline that underrepresents minorities, elderly, and those with common comorbidities. Cruz‑Correa urged sponsors and cooperative groups to open clinical trials at nonacademic centers, at the community level, and to make clinical trials a less centralized, difficult‑to‑get process. She highlighted clinical trial design to have eligibility with inclusion of underrepresented groups as a principle rather than an afterthought. She believes the FDA and funding stakeholders can help by working together to remove logistical barriers and incentivize community participation. The outcome is twofold: equal access improves and evidence generalizes.

Her strongest call to action was metabolic health. “Obesity is a disease, a chronic inflammatory state that is linked to 13 different cancer types, including hepatic, endometrial, gastric, colorectal, esophageal, and kidney cancers,” she said. The AACR Cancer Progress Report looks at how obesity affects incidence, where excess body weight is responsible for 7.6% of all cancers. We need to train the clinical community to consider obesity a disease, and develop a plan to treat the disease, with both lifestyle programs and medications, Cruz-Correa explained.

On the latter, she was explicit: “Now we have medications that have shown to help decrease weight, with GLP‑1 and GLP-2 agonists, alongside dual agonists and other pathways being developed.” For 2026, she envisions the integration of obesity control programs within the prevention and treatment process for cancer patients, with insurance coverage for evidence‑based medications and structured programs. For prevention, she drew an analogy to tobacco: When policy, care, and culture align to reduce exposure, incident disease falls; obesity can be addressed with similar intention.

According to Cruz-Correa, the upcoming year can be fairer to all if government institutions decide to reconfigure thresholds—logistical, financial, and cultural—so the best science reaches the people who need it.

Our experts have a consensus—that breakthroughs in 2026 may not be a single molecule, model, or therapy; they lie in how we connect these innovations—earlier, smarter, and with access that is more consistent across settings—to the right patients, at the right time, under the right policies.