What’s Behind the Increase in Cancer Cases Among Younger Adults?

When you hear the word “cancer,” the image of a young adult likely doesn’t spring to your mind, and for good reason: Historically and biologically, cancer has been a disease of aging. The human body—enduring, in the course of its duties, the slings and arrows of carcinogen exposure, stress, and plain old cellular incompetence—accumulates opportunity for cancer to emerge as time marches on.

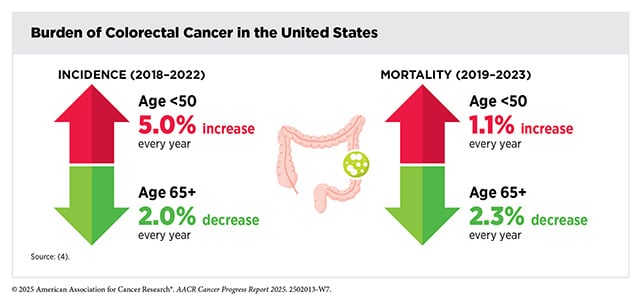

The default assumption that cancer is a disease of advanced age, however, has grown increasingly unreliable due to the sharp recent increase in cancer incidence among those under age 50. While increasing age remains a dominating driver across all cancer cases, the growing trend of early-onset cancers—up more than 15% since 2000—presents questions and challenges beyond the ongoing goal to improve diagnosis, intervention, and treatments.

That’s why, in 2025, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) organized a meeting to address this emerging challenge head-on. At the AACR Special Conference in Cancer Research: The Rise in Early-onset Cancers—Knowledge Gaps and Research Opportunities, researchers from around the world gathered to share their findings on what may be driving the increase as the first step in developing strategies to counteract it.

The 20th Century: A Carcinogen?

After World War II, many countries (particularly those in the global North and the West) experienced previously unthinkable growth and prosperity. In the United States, new institutions invested heavily in the sciences, including biomedical research, and the resulting 12.1% drop in U.S. cancer mortality from 1950 to 2010 (the equivalent of millions of lives saved) is just one reflection of the astounding progress that postwar technological achievement has made.

But the AACR Special Conference’s first plenary session, the “Epidemiology of Early-onset Cancer,” made clear that this progress is at least partially associated with increased cancer risk factors that have come with society-wide advances: environmental changes, a turn to more sedentary lifestyles, ultraprocessed foods, and more. In the words of presenter Rebecca Siegel, MPH, of the American Cancer Society: “something in the middle of the 20th century changed the risk.”

Siegel spoke to the well-known and alarming rise in U.S. colorectal cancer incidence—up more than 62% since 1975—which she described as “a proxy for human development” given its coinciding increase as the 20th century and technological improvements marched forward, making significant changes to humans’ lived environment through processes like urbanization, industrialization, and globalization.

Siegel cited data showing the generational risk of colorectal cancer incidence reversing its previous decline and beginning a steady rise around the year 1950, from which point the risk continued to increase through the 1990s. She also presented data that showed a risk of early-onset colorectal cancer for Americans born in the ’90s about twice that of Americans born in the ’40s. Siegel, however, acknowledged that the latest sharp uptick in early-onset colorectal cancer incidence (up 30.6% from 2019 to 2022) can be partially attributed to recommendations for earlier screening.

Presenter Mary Beth Terry, PhD, a professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, emphasized that screening cannot fully account for the rise in early-onset cancer incidence. She showed that the clonal expansion of abnormal cells into carcinogenic states takes place faster in early-onset colorectal cancer than in nonearly-onset cases, with evidence pointing to environmental exposures. Terry also pointed to early-onset breast cancer incidence even after the baby boom, which cannot entirely be explained by increases in body weight or alcohol use. One potential reason could be exposure during pregnancy to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from scent and flavor compounds in a variety of beauty products and foods, she said, which may explain adolescent breast density (a known risk factor for breast cancer).

Early-onset Cancer’s Eat-iology: Dietary and Metabolic Factors

Although diet was not the only life factor to undergo large changes in the postwar period, what and how people ate changed quite profoundly as the Western diet—high in ultraprocessed foods, sugars, and unhealthy fats; and low in fiber, fruits and vegetables, and whole foods—emerged.

As Yin Cao, ScD, MPH, chair of the session “Mechanisms of Early-Onset Carcinogenesis—Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome,” pointed out, obesity is neither a new problem nor an unknown contributor to cancer. Scientists identified an association between obesity and cancer as early as 1979, she said. Cao, an associate professor at Washington University, stressed that although obesity’s contributors are many, obesity’s impact as a whole is still broadly carcinogenic—which, she said, justifies its study as a composite driver of cancer, especially considering obesity’s 20th century rise.

In unpublished work, Cao drew on the idea of the exposome—a term coined in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention to denote the theoretical totality of environmental and lifestyle factors that we’re exposed to—and estimated lifetime exposure to overweight and obesity by birth cohorts. Her team’s analysis captured both the intensity and duration of excess adiposity and revealed a striking pattern: Younger generations accumulated far greater adiposity exposure by early adulthood than older ones, which translated to a substantial increase in their total lifetime burden. These birth cohort-specific increases in lifetime adiposity exposure mirror the birth cohort effects observed in early-onset cancer incidence, Cao said.

“Something in the middle of the 20th century changed the risk.” -Rebecca Siegel, MPH

Senior Investigator Meredith Shiels, PhD, MHS, of the National Cancer Institute, presented her work demonstrating significant increases in four obesity-related cancers—colorectal, uterine, kidney, and pancreatic—among U.S. 20-49-year-olds from 2010-2022. She also found that these four cancers followed a similar obesity-dependent pattern: From 2018 to 2022, in counties with the highest quintile of obesity, the risk of developing colorectal, uterine, kidney, or pancreatic cancer was significantly higher than in the counties with the lowest quintile of obesity.

One study sought to go beyond obesity as an explanation of early-onset cancer and instead examine one of its hallmarks: fat, or visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Victoria Bandera, a PhD candidate at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, pointed out that not all early-onset colorectal cancer patients are obese. “Obesity contributes to colorectal cancer risk but does not uniquely distinguish early-onset colorectal cancer,” she said.

Hypothesizing that VAT, which is present in obesity but not exclusively so, may play a role in cancer due to its distinct metabolic activity, Bandera and colleagues analyzed VAT samples from 332 patients who either had early- or late-onset colorectal cancer. All patients had similar body-mass indices (overweight but not obese), but preliminary findings from the early-onset VAT samples showed differences in genetic expression, with altered inflammation, metabolism, and proliferation-related pathways—which, Bandera said, indicated how VAT could contribute to a distinct, protumor microenvironment in early-onset colorectal cancer cases.

Small Molecule, Big Impact: Colibactin and Early-onset Colorectal Cancer

Though many presenters spoke about broad-based trends in our environments, a specific factor emerged as a possible explanation for early-onset colorectal cancer: colibactin.

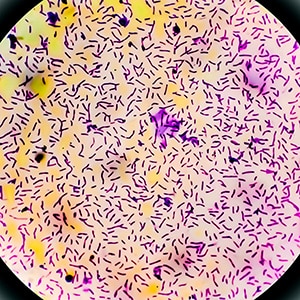

Presenter Ulrike Peters, PhD, MPH—a professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center—explained that the subset of E. coli bacteria with structures known as “pks islands” can produce colibactin, an unstable, toxic molecule that damages DNA. Crucially, colibactin damages DNA in a very predictable way, creating an identifiable colibactin-damage signature: single-base substitution 88 (SBS88).

Peters presented two analyses that found more SBS88-positive colorectal tumors among early-onset cases, and in both studies, SBS88-positive patients were significantly younger at their age of diagnosis than SBS88-negative patients. One of the studies also showed that colibactin damage appears to be an early-life event, likely occurring within the first decade of life.

Mingyang Song, MD, associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, suggested that breastfeeding could explain how some individuals are exposed to colibactin at so young an age. Because breastfeeding provides gut microbiota with a direct transmission route between mother and infant, Song reasoned that colibactin-producing pks-positive E. coli could be among the microbiota transferred.

Early-life penicillin exposure also offers a possible explanation, according to another abstract presented at the AACR Special Conference. First author Max Van Belkum, an MD/PhD candidate at Vanderbilt University, showed that mouse models with colorectal inflammation that were given early-life penicillin not only experienced substantial spikes in pks-positive E. coli levels after each dose—those mice were also more likely to develop colorectal tumors than their penicillin-naïve counterparts. Van Belkum found a similar pattern in human infants too. In a study, infants who had received antibiotics were found to harbor significantly more pks-positive E. coli within their guts.

But how do colibactin’s DNA-damaging effects lead to cancer development in the gut? And why does it seem to play a role in youth specifically?

To answer these questions, presenter Karuna Ganesh, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, developed a new technology to study the highly unstable molecule’s impact on epithelial tissue. Ganesh and her team created a custom “reversible” colorectal organoid that flipped its basal and luminal sides based on polarity—which allowed the team to deliver colibactin-producing bacteria into the lumen.

Ganesh and colleagues found that colibactin damage caused gut tissue to revert into a stem-cell state, from which cancer would be more likely to emerge, she said. Cellular de-differentiation into a stem state is more feasible at younger ages during development, which, Ganesh said, showed how colibactin damage could explain early-onset colorectal cancer as a phenomenon distinct to youth.

A Change Within: Endogenous Factors of Early-onset Cancer

Despite the undeniable significance of exogenous risk factors, cancer does not merely pop into existence after someone has been exposed to a biological insult. Rather, its emergence relies on key biological processes within our own bodies that can aid and abet the development of tumors.

Sheetal Hardikar, MPH, PhD, MBBS, an associate professor at the University of Utah and Huntsman Cancer Institute, presented findings from an Oncology Research Information Exchange Network (ORIEN) analysis of early-, average-, and late-onset colorectal cancer cases to identify genes and processes that could be related to age of onset. Hardikar and colleagues initially analyzed differences in the consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) between early- and late-onset colorectal cancer. Where early-onset colorectal cancers were enriched in CMS4 and depleted in CMS2 and CMS3, late-onset colorectal cancers were enriched in CMS2 and CMS3 but depleted in CMS4.

Hardikar and colleagues also identified 328 genes that were differentially expressed between early- and late-onset colorectal cancer, with early-onset cases showing an enrichment in calcium-channel and Hedgehog signaling pathways. These differences in signaling, Hardikar said, suggested that carcinogenesis in early-onset colorectal cancer involved complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors.

A Need for More Research

Though the AACR Special Conference covered several possible explanations for the rise of early-onset cancer, a tacit consensus emerged that much more research is needed on a problem that’s likely caused by several interacting factors. As the understanding of the exposome continues to grow alongside ongoing research on the fundamental biology of cancer, scientists will continue to uncover the hows and whys of early-onset cancer.

All the chemicals people consume or are otherwise are exposed to should have due diligence done on them. It seems like they discover one of them is found to cause problems monthly.