What Are Fusion Proteins in Cancer?

Fusion proteins can be great. Molecules like monoclonal antibodies, bi- and trispecific T-cell engagers, and bifunctional antibodies are fusion proteins engineered in the lab to target specific molecules in cancers, and such therapies have ushered in a new era of progress in cancer research. But not all fusion proteins work against cancer—some work for it.

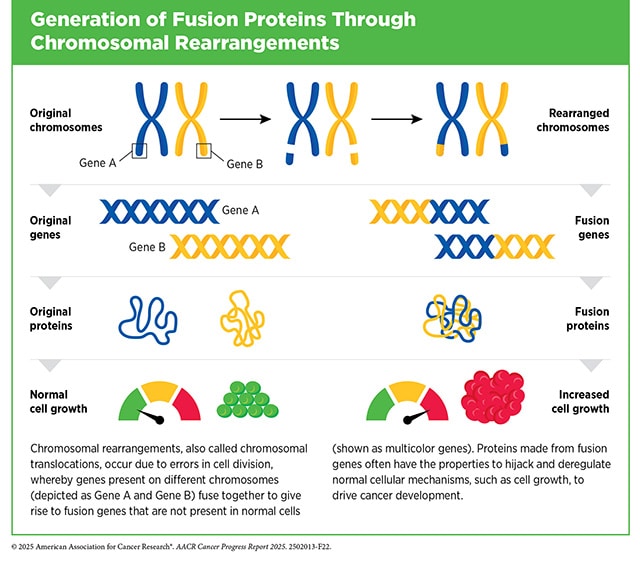

When cells sustain genetic damage—a critical step on the road to carcinogenesis—the complex gene-protein order can become dysregulated if the damage and its attendant errors aren’t corrected. This can lead to pro-cancer, protein-related errors, such as nonsense proteins, the overproduction of pro-growth proteins, or partial shutdowns of necessary protein production. Fusion proteins, however, result from a distinctive kind of biological error: They are the product of formerly separate genes that have erroneously recombined into a single so-called fusion gene. These fusion genes, in turn, produce biologically active, functional, fusion proteins.

At the AACR Special Conference in Cancer Research: Fusion-Positive Cancer: From Discovery to Therapy, held in Philadelphia from January 13-15, 2026, Arul Chinnaiyan, MD, PhD, FAACR—a professor at the University of Michigan Medical School and renowned expert on oncogenic gene fusions—presented work on fusion proteins in prostate cancer. After his talk, he gave Cancer Research Catalyst his perspective on why fusion genes and fusion proteins contribute to cancer’s development and growth. “In general, it’s a bad thing to rearrange your genome,” he said, underscoring the importance of genomic stability in human health. When fusion proteins start influencing how cells function, Chinnaiyan said, the cells that express them can develop abnormal survival advantages—which allow those cells to outgrow normal cells and become cancerous.

What Are Examples of Fusion Genes in Cancer?

In 1960, researchers discovered the first known fusion gene: BCR-ABL1, or the “Philadelphia chromosome” as it came to be known, which can be found in the majority of chronic myeloid leukemia cases and drives the runaway growth of white blood cells. Since then, many more fusion genes and their chimeric protein products have been implicated in a variety of cancers—known as “fusion-positive” cancers when fusion proteins or genes are detected.

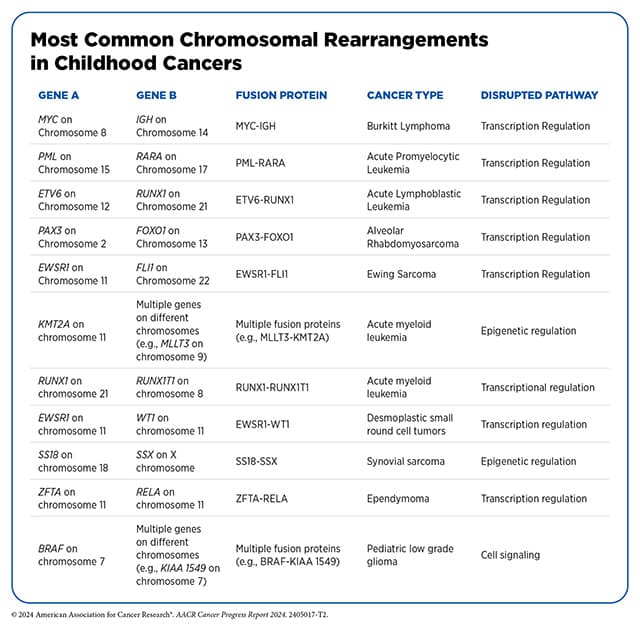

Cancers known to have fusion-positive variants include lung, thyroid, and prostate cancers, as well as certain sarcomas and leukemias. Fusion proteins drive certain childhood cancers as well, as detailed in the 2024 edition of the AACR Cancer Progress Report. Some fusion genes are highly specific to certain cancers, like EWS-FLI1, which is a hallmark of Ewing sarcoma and alters transcription to the cancer’s advantage. Other genes, like NRG1, have been observed fusing with other genes in several combinations across different cancers.

What Treatments Are Available to Treat Fusion-positive Cancers?

Because fusion proteins often drive cancer by wreaking biological havoc—variously, increasing cell proliferation, preventing cell death, and more—they present many opportunities for cancer researchers looking for druggable targets. Targeted cancer treatments typically go after molecules that are highly expressed in cancer cells but are also present in healthy cells, and consequently, such therapies can affect healthy cells too—leading to off-target toxicities. Oncogenic fusion proteins, however, only emerge in abnormal cells and contexts and therefore can present “exquisitely specific” targets, Chinnaiyan explained.

Following decades of research on fusion genes and proteins, targeted cancer treatments began to emerge—appropriately, with a drug that counteracted the Philadelphia chromosome. In 2001, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the drug imatinib (Gleevec) to target the protein-tyrosine kinase made by BCR-ABL1.

Since then, many more fusion-protein-targeted drugs have followed on the heels of fusion protein discovery. Some examples include pralsetinib (Gavreto), which targets the RET fusion protein (discovered in 1985) in adult metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and advanced thyroid cancer; and entrectinib (Rozlytrek), which targets fusion proteins involving NTRK (discovered in 1986) in pediatric and adult solid tumors. And progress in fusion protein-specific therapies is ongoing. The results of a clinical trial at the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets, held October 22-26, 2025, showed that the drug zenocutuzumab (Bizengri) led to a 37% overall response rate in patients with NRG1-positive cholangiocarcinoma (a rare cancer of the bile duct).

Researchers like Chinnaiyan continue to pursue a deeper understanding of fusion proteins’ specific functions in cancer with the aim of developing and improving more targeted treatments. A recently developed open-access tool from the University of Texas Houston School of Public Health at Austin, for example, allows researchers to access well-annotated datasets of cancer-associated fusion proteins’ chemical structures. Using tools like this one, scientists can simulate how fusion proteins might interact with drug candidates—which scientists can use to develop future therapies. As researchers clarify fusion proteins’ characteristics and specific role in cancers, possible therapies continue to emerge.

To learn more about research topics in fusion-positive cancers, check out the conference program for the AACR Special Conference, Fusion-Positive Cancer: From Discovery to Therapy.