AACR IO 2026 Keynote Highlights: Cancer Vaccines Are Here, and Upgrading T Cells To Thrive in the Tumor Microenvironment

The second annual AACR Immuno-Oncology Conference (AACR IO), whose theme is “Discovery and Innovation in Cancer Immunology: Revolutionizing Treatment through Immunotherapy,” opened Wednesday, February 18, in Los Angeles.

With more than 600 registrants and 250 submitted abstracts, the conference is a testament to the growing interest in immunology research for cancer care.

For Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, FAACR, cochair of the conference, former AACR President, and an editor-in-chief of the AACR journal Cancer Immunology Research, the conference fills a gap the field has long needed filled. “This is a conference bringing together basic, translational, and clinical research in immunology and immunotherapies for cancer,” he told attendees at the opening session.

Ribas, who is also professor of medicine, surgery, and molecular and medical pharmacology and director of the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, added, “Immunotherapy provides a realistic chance of having a durable response and cure in some cancers in patients with well-spread metastasis—we need to continue to advance the basic science, translational sciences, and clinical applications to be able to effectively treat more patients,” explaining the driver behind the development of AACR IO. One third of the AACR’s membership identifies as cancer immunology researchers—a statistic that speaks to how central immunotherapy has become not just to oncology, but to AACR’s position as a leading presence in this field.

Nina Bhardwaj, MD, PhD, FAACR, cochair of the conference, expressed her thoughts on how the conference was the result of the extraordinary efforts of AACR leadership: “Envisioning the AACR IO conference under Dr. [Margaret] Foti’s extraordinary leadership of AACR, and bringing it to life together has been an absolutely wonderful experience,” she told the assembled crowd. “We have been able to invite extraordinary scientists, and you’ll see a lot of wonderful advances at this meeting.” Bhardwaj is the director of immunotherapy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The conference’s opening keynote session featured two thought leaders working at the intersection of immunology and cancer—and their talks sketched a vivid portrait of where the field stands and where it needs to go next.

The Era of Cancer Vaccines Has Arrived

Elizabeth M. Jaffee, MD, FAACR, former AACR President and an editor-in-chief of Cancer Immunology Research, opened her keynote by placing cancer vaccines in the spotlight. The title of her talk, “The Cancer Vaccine Era Has Arrived,” showcased the culmination of years of work as a titan in the field of immunology.

Jaffee, deputy director of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, first laid out the landscape. Overall cancer death rates in the United States have declined by nearly 34% since 1991, a figure documented in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2025. The steepest portion of that decline, she noted, coincides with the rise of immunotherapy from 2011 onward. Anti-PD-1 antibodies, anti-CTLA-4 agents, their combinations, and more recently anti-LAG-3, have together generated more than 40 approved indications from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration spanning 17 different tumor types, including cancers that most immunologists once considered immune-cold, such as non-small cell lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. Beyond checkpoints, at least seven CAR T-cell therapies have now been approved for blood cancers, one T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy for uveal melanoma, and one tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy for advanced melanoma. Ten bispecific T-cell engagers have received approval as of 2025.

But Jaffee’s central argument was about what comes after these technologies. Checkpoint inhibitors work in only 20% to 30% of cancers, and even within that subset, most patients are not cured. “Most cancers do not have natural T cells because they mask their antigens, so you can’t find T cells, or if you just find T cells in a tumor, they’re nonfunctional.” Vaccines can fill that void—but only if they can generate T cells of high enough quality, directed against antigens of high enough specificity, and combined with agents that enable those T cells to function inside the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, she noted.

The recent wealth of computational studies into cancer vaccines has made personalized cancer vaccines more feasible, explained Jaffe. Sequencing an individual patient’s tumor and identifying private neoantigens that were essentially undetectable 15 years ago is now routine. Computational pipelines can predict which mutated peptides will be presented on a patient’s major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules.

The platforms themselves—mRNA vaccines encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles, synthetic long peptide vaccines, dendritic cell vaccines—have matured considerably, and the nanoparticle formulations can now be engineered to deliver antigens and adjuvants simultaneously while targeting specific anatomical compartments like lymph nodes. (Read more about some of these approaches in our “From the Bench” post on cancer vaccines.)

Jaffee showcased data from her group’s vaccine research programs, which have focused primarily on pancreatic cancer, a disease notorious for its immune exclusion and its near-universal lethality once metastatic, as well as liver and colorectal cancers. Her team has pursued two distinct antigen strategies: a fusion protein vaccine for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, and a multipeptide vaccine targeting mutated KRAS in pancreatic and colorectal cancers.

The forward-looking part of Jaffee’s talk concerned disease interception in individuals with pancreatic cysts, known as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), which carry a meaningful risk of malignant transformation. These individuals—many of them otherwise healthy people over 50 who happen to harbor multiple KRAS mutations in their cyst cells—represent an opportunity to vaccinate before cancer ever develops.

“We’re hoping that we will be able to detect whether or not these T cells are actually getting into the precancerous lesions,” Jaffee said, noting that a prospective surgical study is now underway in which patients receive the vaccine before planned resection of their IPMN, allowing the team to directly examine the precancerous tissue for vaccine-induced T-cell infiltration.

Taking T Cells Where Natural Evolution Hasn’t

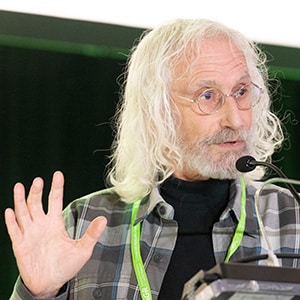

Philip D. Greenberg, MD, FAACR, former AACR President and professor and head of the immunology program at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center at the University of Washington, delivered the conference’s second keynote on “Taking T Cells Where Natural Evolution Hasn’t: Sustained Function in the Tumor Microenvironment.”

While Jaffee’s talk was about generating the right T cells, Greenberg’s was about what happens to those T cells once they reach a solid tumor—and why biology seems to conspire against them. The central problem, he explained, is well-known but incompletely solved: T cells that are engineered and infused into patients with pancreatic cancer become dysfunctional—they infiltrate, find the antigen, and even show initial signs of killing, but within days to weeks, they are silenced by the tumor microenvironment in ways that checkpoint blockade alone cannot rescue.

Greenberg walked the audience through data from a clinical trial his group conducted in pancreatic cancer patients, in which autologous T cells were genetically modified to express a T-cell receptor specific for mesothelin—a surface antigen described in part by Jaffee’s group and highly expressed in pancreatic cancer. Patients received repeated infusions, with tumor biopsies taken before and after each one to track what was happening at the site of disease.

“All the patients showed disease progression—some of the tumors are orchestrating a tumor microenvironment that has lots of strategies that are going to mediate immune evasion and induce T-cell dysfunction,” Greenberg said. “We understood that it would take a complex set of modifications rather than a single strategy to reverse the obstacles that T cells are facing in solid tumors.”

He then walked through three interconnected engineering strategies his group has developed in response, which included:

- targeting a transcription factor identified through computational analysis of exhausted T-cell datasets as a key driver of both the exhaustion and TGF-beta signaling signatures seen in tumor-infiltrating T cells;

- redesigning the TGF-beta receptor itself by replacing its suppressive intracellular signaling domain with components of the IL-2 receptor so that TGF-beta in the tumor microenvironment becomes a T-cell growth signal rather than an inhibitory one; and finally,

- overexpressing the KLHL6 protein in engineered T cells in mice to push the T cells toward a more memory-like state.

All three strategies are now being integrated, and Greenberg presented early data from a clinical trial using KRAS G12A-specific TCRs introduced into both CD4 and CD8 T cells—a design informed by evidence that CD4 T cells are critical not just for direct tumor killing but for preventing CD8 T-cell exhaustion.

“We and many others have found lots of different strategies that look promising, we need to compare all these approaches and figure out which ones can be combined—the kinds of molecular tools we all have now should make that feasible for making the next generation of engineered T cells,” Greenberg said.

These keynotes on the first day of AACR IO 2026 showcased the wealth of work that goes into translating mechanistic insights to real-world impact and underscored how important it is to continue these efforts in the field of immuno-oncology.

As Ribas said, “We need to continue to advance the basic science, translational sciences, and clinical applications to be able to effectively treat more patients.”

Earlier this year, Jaffee served as a cochair of a two-day think tank that was organized by the Cancer Vaccine Coalition (CVC) in partnership with AACR to help foster the next breakthroughs in cancer vaccine research. This event brought together renowned researchers, patient advocates, industry representatives, and policy/regulatory experts to establish actionable strategies to advance the development of cancer vaccines and their ultimate delivery to patients.