Low-Fat Diet Can Improve Outcomes for Breast Cancer Patients

Lowering dietary fat intake reduced death rates in a subgroup of women with breast cancer who were part of the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS).

You know your diet is an important component of your health.

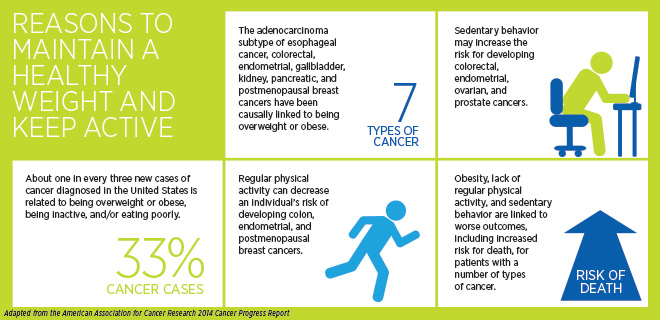

In fact, research shows that adopting healthy approaches to living, including eating well, maintaining a good weight, and engaging in regular physical activity, can reduce your risk of many health conditions including cancer.

An estimated one in three new cancer diagnoses in the U.S. each year are related to being overweight or obese, not getting enough physical activity, and/or having poor dietary habits.

Research presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, suggests that women with certain types of breast cancer who follow a low-fat diet for at least five years have better overall survival, in addition to the lower risk of disease recurrence already reported.

The new data come from a subgroup analysis of 15-year follow-up of the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS). The study started in 1994 with the goal of learning whether lowering fat intake improves outcomes for postmenopausal women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. The study compared women in an intervention group that followed a low-fat diet with a control group.

In 2006, WINS researchers reported that women with early-stage breast cancer who reduced their fat intake for five years had a 24 percent lower risk of relapse than those who did not change their diet.

The latest results provide insight into the influence of lowering fat intake for five years on long-term survival. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in death rates among those who reduced their fat intake for five years and those who did not. However, when the researchers looked at different groups of women, they saw a clear benefit from the low-fat diet.

“In exploratory subgroup analyses, in women with estrogen receptor [ER]-negative cancers, a 36 percent, statistically significant reduction in deaths was seen in women in the intervention group,” according to the researcher and medical oncologist who presented the data, Rowan Chlebowski, MD, PhD, of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Moreover, the reduction was an even more significant 56 percent for women with cancers that were both ER- and progesterone receptor [PR]-negative, Dr. Chlebowski added.

In the WINS trial, those women who were on the low-fat diet reduced how many of their calories came from fat by 9.2 percent and lost about 6 pounds. Thus, the new research adds to the accumulating knowledge about the importance of maintaining a healthy weight throughout life and keeping active.

“For a woman with breast cancer, there are health benefits associated with a 5 percent, 5 pound weight loss,” said Dr. Chlebowski. “This is something that a woman with breast cancer should consider.”

Dr. Chlebowski went on to add that the latest data suggest that if a lifestyle intervention [in this case lowering fat intake] is to have long-term influence on clinical outcome, it must be a lifelong change rather than be a short-term alteration.