Reducing Nicotine in Cigarettes: The Impact on Public Health

Most people know that nicotine is a highly addictive component in cigarettes, which continue to kill about a half-million people each year and account for 30% of all cancer deaths. But do you know how much nicotine is in a cigarette? Or that there have been calls dating back 30 years to make cigarettes less addictive by reducing their nicotine levels? Or that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was granted the power to regulate the manufacturing of cigarettes—including the amount of nicotine in them—in 2009? Or that a significant change in the levels of nicotine in cigarettes could soon be on the horizon?

Currently, the amount of nicotine in a cigarette can vary based on the brand from around 13 to 16 milligrams per gram of tobacco (mg/g). When the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 was passed, it stipulated that the FDA could reduce nicotine in cigarettes as long as the amount was still above zero. After years of research, in 2022, the FDA announced its intention to propose a rule that would set a nicotine product standard—effectively capping the amount of nicotine allowed in combustible cigarettes. In January 2025, the agency formally proposed a nicotine product standard of 0.7mg/g—an approximate 95% reduction of nicotine in cigarettes and some other combustible tobacco products.

For now, this is still a proposal, but the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has long advocated for setting a nicotine product standard and recently published a paper in support of this potential new federal limit on nicotine in combustible tobacco products. The paper, published in the AACR journal Clinical Cancer Research, details the immense benefit such a change would have on public health, including helping an estimated 13 million additional Americans quit smoking within a year of implementation.

Cancer Research Catalyst spoke with two of the paper’s authors: Dorothy K. Hatsukami, PhD, from the University of Minnesota, and Benjamin A. Toll, PhD, from the Medical University of South Carolina, who both serve on the AACR Tobacco Products and Cancer Subcommittee. Hatsukami and Toll explain what this change could mean, what other resources would still be needed to support people who are interested in quitting smoking, and how interested parties can help ensure this rule is ultimately implemented.

What is the main takeaway from your paper about the proposed change in nicotine levels and its effect in the United States?

Dorothy Hatsukami: The proposed change would have a transformative impact on public health in America. FDA modeling suggests that by the year 2100, reducing nicotine levels in cigarettes and other combusted tobacco products as they have proposed would prevent 4.3 million deaths from tobacco-related causes. That’s about as many people who live in the Phoenix or Boston metropolitan areas or in the states of Louisiana or Kentucky. Smoking also leads to many different chronic diseases, so by making it easier for people to quit smoking and less likely for people to start smoking, everyone can be expected to be healthier.

Benjamin Toll: I think the main message of our paper is that the United States has the potential for a watershed moment, where we can truly affect public health on a massive scale to reduce the burden of cancer in this country. Implementing this nicotine product standard is probably the single biggest action that we could do to improve public health for decades to come. And as people become healthier, it is estimated that this rule would benefit the economy by more than $1.1 trillion per year over the next 40 years, even before factoring in resultant increases in productivity and health care costs.

Dorothy Hatsukami: Importantly, this rule is supported by a vast body of research. Numerous clinical trials have shown that reducing the amount of nicotine in cigarettes to very low levels decreases smoking and dependence on the cigarette and increases quit attempts and quit rates. There is also a lot of research that shows that this rule can help people who smoke from all walks of life and the occurrence of negative consequences are likely to be minimal.

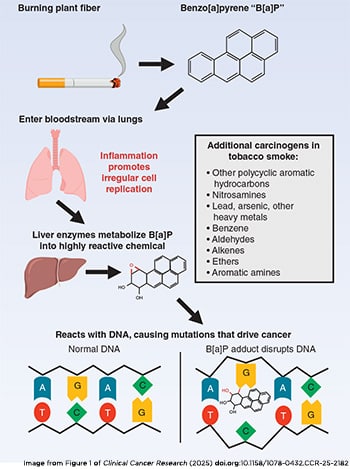

In the paper, you mention how there is a misperception that nicotine causes cancer. For people who don’t understand, can you explain the role that nicotine plays in increasing cancer risk?

Benjamin Toll: My son is a rock climber, and he often climbs on a Kilter board. This board has an electronic database of thousands of named climbs, one of which is “Nicotine is Cancerous.” So, there is still a lot of misinformation out there about nicotine. The fact is that nicotine does not directly cause cancer, but there are 7,000 chemicals in smoke that can cause health problems, and at least 79 of those are known to cause cancer. That is what makes this proposed nicotine product standard so very important for U.S. public health, because if you take out that addictive chemical, fewer people will start smoking and more people will have an easier time quitting.

Dorothy Hatsukami: That is right. The main issue with nicotine is that it leads to continued smoking, which leads to continued exposure to all those cancer-causing chemicals and toxicants that are in the smoke. There are, however, several other health concerns related to nicotine exposure, including the effects on the fetus, increasing some cardiovascular risk factors, and the potential effects it can have on the developing brain. Nicotine is not completely benign.

If you reduce the nicotine levels in cigarettes, is there any concern that this would just lead to people switching to another addictive product or just smoking more?

Dorothy Hatsukami: There’s a possibility that people would switch to another nicotine product, which is why it’s important to also lower the nicotine in other combusted products such as cigarillos and little cigars, pipe tobacco, and roll-your-own tobacco. Those products are also being considered as part of this proposed rule and would help ensure people don’t go from one highly toxic, highly addictive product to another one. Another possibility is that people would seek out e-cigarettes, nicotine pouches, or other alternative products, but these products are less toxic than cigarettes.

The best-case scenario would be that people quit the use of any tobacco product, or use nicotine replacement therapies or other smoking cessation medications as a bridge to get there. What we haven’t seen in past studies is that low nicotine cigarettes cause an increase in intensity of their puffs or smoking more cigarettes per day—it isn’t really physically possible to smoke enough very low nicotine cigarettes to make up the difference.

The paper talks about a “continuum of risk” between the various available nicotine products. Can you explain that continuum and the harms of cigarettes versus e-cigarettes?

Benjamin Toll: While no tobacco product is safe, the level of harm is greatest when there is combustion involved, because the toxicants created during the process of combustion are what make up the majority of carcinogens in smoke. So, the continuum of risk starts with nicotine products that are not risky at all, such as medicinal products designed to help people quit smoking, like nicotine patches. The level of risk is higher with products like chewing tobacco or moist snuff and e-cigarettes, where there is no smoke but there are other harmful chemicals. Those products expose the end user to fewer known toxicants and carcinogens but do still confer some harm to the user. Combustible cigarettes are at the most dangerous end of the spectrum. This nicotine product standard will help to drive tobacco users down this continuum of risk.

Dorothy Hatsukami: However, the optimal goal is to not just turn cigarette smokers into vapers; it is to help people quit using nicotine products completely. Moving people away from smoking is an important first step, and for some people, using products down the continuum of risk can be an alternative.

Benjamin Toll: Absolutely, and I would add I am very opposed to non-nicotine users starting to vape, especially youths. So this concept of moving down the continuum should only apply to adult cigarette smokers. For adolescents and young adults, there’s unequivocal data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) that most are just not smoking cigarettes. They are using e-cigarettes instead and beginning to have higher levels of nicotine pouch use. I don’t see a way that this rule will change their e-cigarette use patterns. Lower levels of nicotine in cigarettes would only help to further ensure youths don’t start smoking, which is the most dangerous form of tobacco use.

To ultimately get people off nicotine, what other resources or policies would be needed beyond lowering the nicotine levels?

Benjamin Toll: At this time, there are essentially three classes of medicinal treatments for quitting smoking: varenicline (Chantix), bupropion (Zyban), and nicotine replacement therapy in the form of patches, gums, and lozenges. While we know that those work for helping people who want to quit, quit rates are still low and there hasn’t been a new treatment approved in this area in about 20 years. Emerging data show that certain classes of users such as dual users—a person who both smokes and vapes—require much higher doses of nicotine replacement therapy to quit effectively. So, what we need most are clinical trials to investigate new treatments to help people stop the use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and other tobacco products. Additionally, making sure these treatments are covered by insurance would increase their accessibility, and allow people of all backgrounds to reliably use them to quit.

Dorothy Hatsukami: Beyond medications for help to quit smoking, there are other resources available like smokefree.gov, a site from the National Cancer Institute with different tools to help people quit smoking, including text messaging programs and a smartphone app. There are also state quitlines that offer similar tools or that people can call to speak with a counselor. Behavioral counseling increases the effectiveness of the available smoking cessation medications, which is why it is important that those services and pharmacological products are both available and affordable.

Benjamin Toll: That is why I’m troubled that those state quitlines are being and may continue to be defunded at the federal level. They receive a lot of support, both financial and training, from federal programs. It’s very challenging to lose that, especially for states like mine—South Carolina—that are extremely rural. In parts of my state, it can be a two-hour drive to the nearest hospital. What’s great about the quitline is you can get care straight from your home. These programs are especially crucial in rural areas because in places like Kershaw, South Carolina, the smoking rates are double the national rates.

The paper also mentions studies examining the effects of lower nicotine levels in specific populations. What did you find, and how does it impact approaches that are aimed at helping people of different races and ethnicities to quit smoking?

Dorothy Hatsukami: While we found that very low nicotine content cigarettes helped to decrease smoking and increase the probability of quitting across many different populations, the effect may be reduced in certain populations such as Blacks compared to whites. That just emphasizes the need to ensure other resources to quit smoking are available to these populations.

What reaction do you expect from the tobacco industry on this potential change?

Benjamin Toll: There is unequivocal evidence of how the tobacco lobbying base has invested heavily in the past to vigorously fight changes that impact their industry. And that’s why, in my opinion, we need to rally public health groups to not only fight for this rule but also to better educate the public about this rule and its many benefits.

Dorothy Hatsukami: Tobacco companies could raise the concern of creating an illicit cigarette market. While I don’t think the illicit marketplace is going to be as big based on a survey that we conducted, we still need to have regulations in place, including a good track-and-trace system for cigarettes that would help identify any kind of illegal cigarettes that come into the marketplace. Over time, we expect that the population that remains smoking is going to get smaller and smaller, and in turn, any illicit marketplace should diminish as well.

What are some of the critical next steps for this proposed rule to be implemented?

Benjamin Toll: It’s very important that multiple medical and public health organizations like the AACR, Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, American Lung Association, American Heart Association, and others continue making noise about this proposed rule, and encourage members and other interested parties to submit letters to the FDA that push them to pass this incredibly important rule.

Dorothy Hatsukami: It’s also going to be important to communicate the benefits of this rule to the public and obtain feedback on any concerns. We have found that the majority of people support it, regardless of whether they smoke or not, especially if the rule will prevent younger generations from starting to smoke and if it helps people quit smoking. The benefits to the physical and economic health of all Americans will be profound.