What Are the Options for Colorectal Cancer Screening?

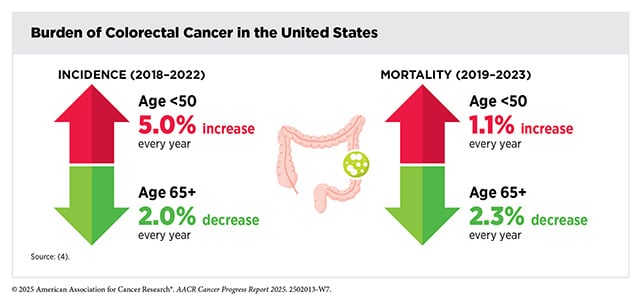

Colorectal cancer is on the rise in younger adults. Incidence in people under 50 has risen by more than 30% since 2019, and though scientists have some developing explanations ranging from obesity and exposure to bacterial toxins, we don’t yet know definitively what’s causing the especially pronounced increase of early-onset colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer tends to have a decent prognosis if it’s detected early (91.5% five-year relative survival rate for localized disease), but as a cancer that’s predominantly associated with an older patient population, colorectal cancer’s increasing early-onset incidence may pose a distinct threat to younger patients, who might not catch it at the earliest, most treatable stages. Already, colorectal cancer is the leading cause of non-sex-specific cancer death in U.S. residents under 50, and in 2021, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age of colorectal cancer screening for adults without elevated risk from 50 to 45.

Unlike some other cancer types with obvious or distinctive symptoms (e.g., melanoma’s telltale suspicious moles), the symptoms of colorectal cancer can overlap with less threatening gastrointestinal issues—and, appearing banal, they run the risk of being ignored.

Common symptoms of colorectal cancer include bloody stools, abdominal discomfort, and constipation—all of which might be confused with symptoms of Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and even “runner’s trots,” the IBS-like affliction that many habitual runners know all too well.

Taking note of concerning symptoms is a great habit, but personal vigilance can only go so far. Luckily, there are more colorectal cancer screening options available than ever that can reduce the risk of late detection and its ill effects.

Colonoscopies: Recommended, Reliable, and Reviled

There are two principal facts to highlight about colonoscopies: They are far and away considered the gold standard for colorectal cancer screening, and nobody likes a colonoscopy.

That many U.S. adults are not up to date with their recommended colorectal cancer screening, while a challenge for public health, is understandable (although compliance has risen substantially over the past few decades, including the interval since this blog covered the subject). What colonoscopy entails—the insertion of an endoscope into the rectum and colon, which allows clinicians to screen for tumors and, in some cases, remove precancerous polyps—may strike some as unpleasantly invasive, and fears of an uncomfortable or painful experience might give patients further pause. The necessary colon preparation, which requires fasting and a large dose of laxatives to ensure that the colon is completely empty, is no walk in the park either.

The admitted inconvenience and unpleasantness of a colonoscopy, however, pale in comparison with the consequences of a colorectal cancer diagnosis. Even stage 1 disease requires treatments that come with side effects—most often surgery, which requires preparation similar to that of a colonoscopy anyway—to say nothing of the risk of disease progression or even mortality.

But for those who may hesitate to undergo screening, it’s also worth noting that contemporary colonoscopies are a far cry from what they used to be. Sedation with drugs like propofol has become the norm, which essentially eliminates the possibility of mid-procedure discomfort.

And although colonoscopy prep formula—a commonly prescribed solution that empties the bowels by inducing diarrhea to make the colon lining visible for examination—has a reputation both for its taste and required quantity, patients now have the option of preparing for their colonoscopies with a simple pill regimen.

Colonoscopies are also, by dint of their thoroughness, only recommended once every 10 years for adults aged 45 or older without elevated colorectal cancer risk. Other tests, though less involved, should be performed more frequently, according to the USPSTF.

Still, when it comes to colorectal cancer prevention, the perfect need not be the enemy of the good, and for those who’d prefer to avoid the annoyances attendant to colonoscopies, other screening options have emerged. But when patients receive positive results on such tests, they will likely require a colonoscopy for definitive cancer diagnosis.

Colonoscopy-lite: The Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

A close cousin of the colonoscopy, the flexible sigmoidoscopy allows patients to undergo colorectal cancer screening comparable to that of a colonoscopy but without such stringent requirements of bowel preparation; per the National Cancer Institute (NCI), only the lower colon need be emptied prior to a sigmoidoscopy. Unlike a full colonoscopy, the flexible sigmoidoscopy assesses the sigmoid colon (the part of the colon immediately adjoining the rectum) rather than the colon’s entirety.

Not all health care providers offer flexible sigmoidoscopy, and the NCI notes that the procedure isn’t widely available in the United States. But this screening method offers a streamlined option where available, and it provides a useful alternative in countries and regions where health care resources may be limited. The USPSTF recommends that, for those 45 and older who elect to screen for colorectal cancer with flexible sigmoidoscopy, screening should be repeated every five years.

Picture? Perfect! Imaging Methods for Colorectal Cancer Screening

As a procedure whose diagnostic power lies chiefly in visual assessment rather than biological testing, the colonoscopy is comparatively low-tech; fundamentally, it relies on nothing more than a camera and clinician dexterity.

But endoscopes are not the be-all, end-all in imaging technology. The medically ubiquitous X-ray has been adapted to the computed tomographic (CT) colonography, which eliminates the need for an endoscope or anesthesia by creating an image of the colon from an exterior scan. The NCI lists CT colonography’s convenience factor as a benefit but also notes that the method may miss smaller polyps, and the USPSTF recommendations advise the test’s use every five years.

X-rays aren’t the only imaging-based alternative to traditional colonoscopy. Although tiny cameras might have once been the exclusive province of espionage, miniaturized imaging technology has come to revolutionize countless fields—including medicine.

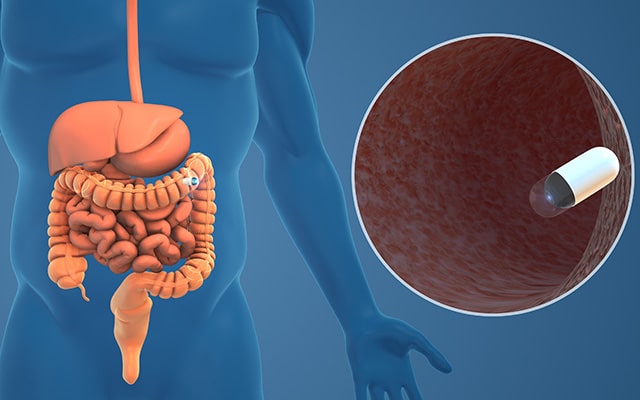

The capsule endoscopy is just what it sounds like: a swallowable capsule with embedded miniature cameras and a light source that can travel the length of the digestive tract and record it in detail, allowing physicians to analyze the images for polyps and lesions. Once it completes its journey, the camera pill is harmlessly excreted and flushed away. In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved one such “pill cam,” which can be used to screen for colorectal cancer. However, its approved indications are limited to use as a follow-up for incomplete colonoscopies and for patients for whom traditional colonoscopies pose risks.

Advanced Needlework: Cancer Screening With Blood Tests

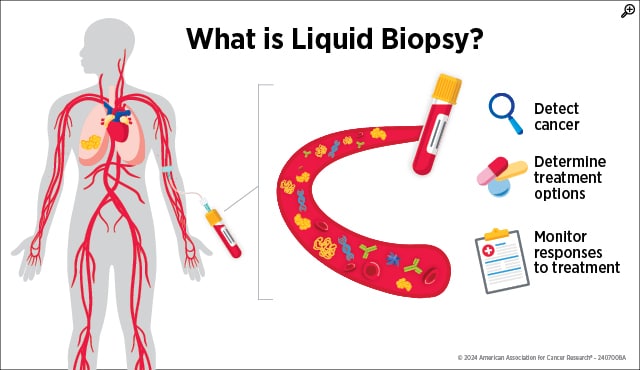

A single vial of blood can contain a treasure trove of biological information, and increasingly, researchers and clinicians are using liquid biopsies to aid in cancer care, including diagnostics. The first FDA-approved blood test for colorectal cancer screening, Epi proColon (now ColoHealth), was approved in 2016 for adults who have not yet completed their recommended colorectal cancer screenings after being offered. The test uses epigenetic analysis to make its determination, meaning that it assesses changes in the structure of genetic material. Specifically, Epi proColon screens for colorectal cancer by quantifying the methylation of the gene Septin-9, which is often highly methylated in colorectal cancer.

The Shield blood test, another liquid biopsy screening method, received FDA approval in 2024 and offers patients another noninvasive colorectal cancer screening option (and as its label notes, the test is intended, though not required, to be performed alongside other routine bloodwork). By analyzing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in the blood, the Shield test screens for colorectal cancer’s presence by assessing whether the cfDNA has patterns consistent with colorectal cancer, like certain mutations and DNA methylation. Results from the clinical trial that led to the Shield test’s approval found that it could successfully predict 87.5% of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer cases and 90% of metastatic colorectal cancer cases.

Like other noninvasive colorectal cancer screening methods, both blood tests require diagnostic confirmation with a colonoscopy if they indicate that colorectal cancer may be present. However, the tests’ blood-based nature offers patients the opportunity to complete their recommended colorectal cancer screening in the regular course of preventive health care.

Poo It Yourself: At-home Fecal Sampling Kits

If blood, which travels all throughout the body, can be used to detect colorectal cancer, then a biological product straight from the colon’s neighborhood should certainly be a viable option for testing. Not one, not two, but three types of tests screen for colorectal cancer by analyzing what can no longer escape mention: poop.

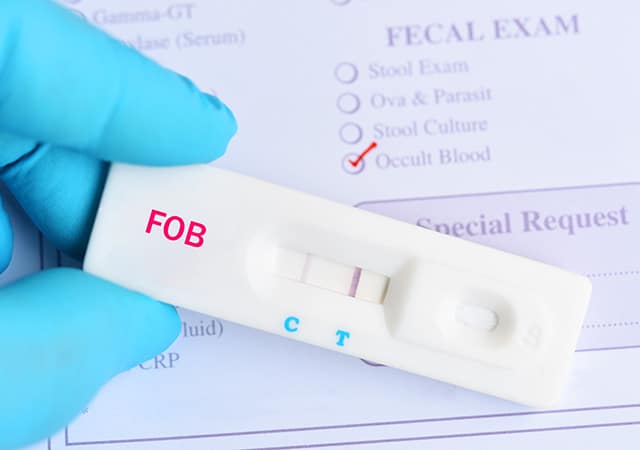

The three main types of stool-based screening tests for colorectal cancer are:

- the guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT; sold under a variety of brand names), which chemically detects a component of the blood-based protein hemoglobin called heme and requires a heme-restricted diet prior to use;

- the fecal immunochemical test (FIT; sold under a variety of brand names), which also tests for heme, but uses antibodies to do so and does not require dietary changes; and

- the multitarget stool DNA testing (sDNA-FIT or mt-sDNA; sold as Cologuard and Cologuard Plus), which analyzes stool DNA for colorectal cancer indicators while also checking for hemoglobin. The USPSTF recommends annual testing for both gFOBT and FIT but once every one to three years for sDNA-FIT.

There’s no doubt that stool sampling—which involves depositing a certain amount of feces in a sample container or smearing it on a card—can be unpleasant. However, in addition to being noninvasive, stool-based tests offer the distinct advantage of at-home use and convenience, which may explain their rising popularity. The results of a national survey published in Cancer Prevention Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), found that stool-based tests were overwhelmingly preferred to colonoscopies. Compared with colonoscopy, gFOBT or FIT and sDNA-FIT were preferred by 61% and 65.4% of respondents, respectively.

sDNA-FIT, however, seems to be uniquely popular, as the same survey found that it was preferred over gFOBT or FIT by 66.9% of respondents. And a recent study, also published in Cancer Prevention Research, found that sDNA-FIT usage went from accounting for less than 1% of insured colorectal cancer screenings in 2016 to 17% by 2022 (an increase of more than 94%). The same study also found that rural patients were significantly more likely to choose sDNA-FIT over colonoscopy than urban patients, which suggests that at-home screening may have particular appeal to those who live further from health care providers.

Researchers are also continuing to refine these tests to improve non-colonoscopy screening’s reliability. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of AACR, published a study showing that FIT can be made even more accurate if combined with a blood draw that scans for circulating tumor cells (CTC). The researchers’ FIT-CTC model had an area under the curve (AUC; a measure of a classifying test’s accuracy, where a score closer to one indicates better performance) of .8371, compared with the FIT-only AUC of .7555.

However, the self-administered nature of these tests does come with the drawback of operator error. According to a retrospective study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, more than 10% of FIT tests were unusable for screening due to unsatisfactory samples. The most common issue with the problematic tests? Not enough stool.

Follow-up on test results is also extremely important. As Cancer Today reported, one study showed that only about half of patients who received a positive FIT result eventually followed up with a colonoscopy—a striking reminder that colonoscopy uptake remains a public health challenge.

All Roads Lead to the Colon

In light of increasing early-onset colorectal cancer incidence, both the widespread availability of different screening options and the USPSTF’s updated guidelines provide a robust framework for detecting colorectal cancer earlier—which is critical for positive outcomes. Encouragingly, after the recommended colorectal cancer screening age was lowered from 50 to 45, screening rates have trended in the right direction.

A new study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention analyzed patient health records from the University of Washington health system and showed that colorectal cancer screening completion in eligible U.S. adults rose from 61.8% in 2021 to 70.8% in 2024. During the same period, the rate of completed screening in 45-to-49-year-olds doubled, from 25.6% to 51.7%, while gaps in screening completion between racial groups narrowed.

Whether patients decide to opt for traditional colonoscopy or try a less invasive alternative, what matters most in the final account is that patients are up to date with their recommended colorectal cancer screening—and, should those screenings produce any concerning findings, that the necessary follow-up steps are taken to get a definitive diagnosis for further management. An ounce of prevention, be it in a blood vial or a sealed sample cup, is worth a pound of cure.