Low-dose Aspirin Goes Beyond COX-1: Exciting New Mechanistic Insights Into Cancer Prevention

If you are someone who would bet all your chips on helping people not get cancer in the first place, the AACR International Conference on Frontiers in Cancer Prevention Research is the place to be. This year, at the 13th annual conference in New Orleans, cancer prevention researchers gathered and discussed a wide range of topics enriched with new data that contribute to our understanding of cancer development and may lead to better prevention strategies.

Among these topics was cancer prevention with aspirin – an exciting and increasingly promising prospect.

A study, presented by researchers at Duke University School of Medicine, used data from 3,960 men who participated in the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events (REDUCE) study and found that aspirin and/or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) lowered the risk for aggressive prostate cancer by 17 percent, irrespective of their prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels. The study found that NSAIDs only lower PSA by a small amount, and that this would have no effect on PSA’s ability to predict prostate cancer in these men.

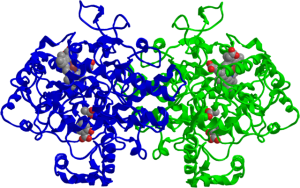

With a multitude of studies suggesting aspirin’s cancer preventive effects in recent years, the intrigue now turns toward its mechanism of anticancer action. As I discussed in an earlier post, existing knowledge suggests that the antiplatelet effect of low-dose aspirin via inhibition of the COX-1 pathway may play a role in lowering the risk for many different cancers.

However, new data presented by a team of researchers at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine suggest that low-dose aspirin may do more than just hit the COX-1 pathway: It may also inhibit COX-2 and lower the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).

“We found that the potency of low-dose aspirin in inhibiting COX-2 in the tumor cells is as great or greater than its potency as an inhibitor of COX-1 in the platelet,” said Pierre Massion, MD, professor of medicine and cancer biology in the Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine at Vanderbilt.

Massion and colleagues found that the doses of aspirin needed to inhibit COX-2-mediated PGE2 production was up to 12 times lower than the dose needed to exert its COX-1-mediated antiplatelet effects, when tested in three lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. The levels of PGE2 and prostacyclin – measured by mass spectrometry – in the urine samples of 54 subjects who took low-dose 81 mg aspirin for two weeks were lowered by 45 percent and 37 percent, respectively.

Finally, the expression of COX-2 and PGE2 in lung adenocarcinoma cells shot up more than eightfold in the presence of activated platelets. Activated platelets are known to facilitate the movement of tumor cells, and therefore, metastasis. So, Massion and his team speculate that the antiplatelet and COX-2 inhibitory activities of low-dose aspirin may act in concert to lower the risk for cancer metastasis and mortality.

The more we understand how aspirin exerts its anticancer effects, the sooner we could find suitable ways to use aspirin safely to lower the risk for cancer and cancer recurrence in those at increased risk.