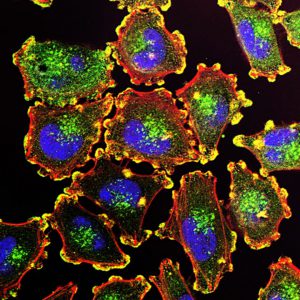

AACR Annual Meeting 2017: Increasing the Number of Melanoma Patients Who Benefit From Immunotherapy

Metastatic melanoma cells. Melanoma is expected to be the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in 2017. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

Immunotherapy has dramatically improved the outlook for patients with advanced melanoma. A group of immunotherapeutics known as immune checkpoint inhibitors, which includes ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), have been particularly transformational.

As highlighted on this blog, clinical trial data presented at last year’s AACR Annual Meeting showed that 34 percent of patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab were alive five years after starting treatment. These results stood in stark contrast to the National Cancer Institute’s SEER data at the time, which gave the five-year relative survival rate for metastatic melanoma patients diagnosed between 2005 and 2011 as just 16.6 percent.

Despite the excitement surrounding the durable response data, they mean that 66 percent of patients on the trial had melanoma that did not respond to nivolumab or progressed after initially responding.

Identifying ways to increase the proportion of patients with melanoma who have clinically meaningful and durable responses to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment is the focus of large numbers of researchers. Earlier today, at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 press conference, two physician-scientists discussed their efforts to address this important challenge.

Harnessing our Understanding of a Different Immune Pathway

Advances in immunotherapy stem from decades of basic research that has enhanced our scientific understanding of the immune system and how it interacts with cancer cells.

In the late 1990s, immunologists discovered that degradation of the essential amino acid tryptophan by the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) played a role in preventing the immune system of pregnant mice from attacking and rejecting their fetuses. Subsequent studies over the next decade established the paradigm that the normal function of the IDO pathway is to keep the immune system in check, not only preventing the immune system of a pregnant woman from attacking her baby, but also preventing the human immune system from causing autoimmune disorders and asthma.

“However, some tumors hijack the pathway, using it to prevent the immune system from attacking and destroying the tumors, suggesting that it could be a good target for cancer immunotherapy,” explained Yousef N. Zakharia, MD, one of the researchers to present at the press conference this morning.

Zakharia, assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Iowa and coleader of the early phase clinical trials program at the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Iowa, presented data from a phase I/II clinical trial in which he and his colleagues tested this hypothesis using the IDO-pathway inhibitor indoximod.

Rather than test indoximod as a monotherapy, they decided to investigate whether targeting the IDO pathway in addition to using an immune checkpoint inhibitor could increase the proportion of patients with advanced melanoma who respond to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

Zakharia explained that in the phase III KEYNOTE-006 clinical trial that led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab as an initial treatment for patients with advanced melanoma, the overall response rate was 33 percent.

“We are excited to share interim results from the phase II portion of this clinical trial, because the data show that 52 percent of patients treated with a combination of pembrolizumab and the IDO-pathway inhibitor indoximod had a partial or complete response without significant added toxicities,” he said. “These robust data are very promising, but we need to confirm the clinical benefit in a larger, randomized trial.”

Using Viruses to Boost the Killing Power of the Immune System

The clinical utility of using viruses that can infect and kill melanoma cells, so called oncolytic viruses, to boost the killing power of the immune system was highlighted in late 2015, when the FDA approved talimogene laherparepvec or T-Vec for short (Imlygic), for the treatment of melanoma lesions in the skin and lymph nodes that cannot be removed completely by surgery.

As discussed on this blog, T-vec is a herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 that has been genetically modified in a number of ways so that it is less able to cause disease, is more selective for cancer cells, and is better able to promote an anticancer immune response.

This morning, Brendan D. Curti, MD, director of the Clinical Biotherapy Program and codirector of the Melanoma Program at the Earle A. Chiles Research Institute of Providence Cancer Center in Portland, Oregon, presented data from a clinical trial testing another oncolytic virus, Coxsackievirus A21 (CVA21; Cavatak).

CVA21 is a bioselected, nongenetically altered common cold RNA virus. According to Curti, it can directly infect many different cancer cells and as such it can boost adaptive and innate anticancer immune responses.

Curti and colleagues are enrolling up to 70 patients with advanced melanoma in the melanoma intratumoral Cavatak and ipilimumab (MITCI) clinical trial. Patients who have and who have not received immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment are eligible for the trial. CVA21 is injected directly into melanoma lesions, while ipilimumab is infused intravenously.

At data cutoff for the presentation, 22 patients were evaluable for response. The overall response rate was 50 percent, with four patients having a complete response and seven patients having a partial response. The median duration of response has not been reached, with a number of responses greater than six months and several still ongoing.

“The preliminary overall response rate of 50 percent is very positive because previous reports indicate an 11 percent overall response rate for ipilimumab alone and an approximately 28 percent overall response rate for CVA21 alone,” said Curti.

What is Next?

These clinical trials show that combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with immunotherapeutics that work in a different way to unleash a patient’s immune system can increase the proportion of patients with melanoma who respond to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. However, they are both small studies, and the promising results need confirming in larger numbers of patients. In addition, we will have to wait longer before we know whether all the responses that have been seen are durable.