A Targeted Therapy Next in Line for Biomarker-based Cancer Drug Approval?

Following the recent groundbreaking approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the immunotherapeutic pembrolizumab (Keytruda) to treat cancer patients based on a biomarker rather than tumor origin, recent data suggest that there is another potential contender for a biomarker-based FDA approval: a targeted therapeutic called larotrectinib (LOXO-101), which showed promising results in adults and children with a variety of cancer types, all of which had one thing in common—fusions involving the gene TRK.

What is larotrectinib?

Chromosomal rearrangements in the genes NTRK1, NTRK2, or NTRK3, which code for the proteins (receptor tyrosine kinases) TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC, produce fusion kinases in a variety of adult and pediatric malignancies. Such fusion proteins activate signaling pathways involved in growth and survival of the cells. Larotrectinib is an inhibitor of TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC.

Larotrectinib received orphan drug status in 2015 for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma and breakthrough therapy designation in 2016 for the treatment of metastatic solid tumors with NTRK fusion in some adult and pediatric patients.

Preliminary data from a phase I clinical trial testing larotrectinib, presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2016 in New Orleans, showed significant tumor regression in all six patients whose tumors had NTRK fusion. Patients had different cancer types, including sarcoma, papillary thyroid cancer, salivary gland tumor, lung cancer, and GI stromal tumor.

At the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, held June 2-6, 2017, data from three studies testing larotrectinib were presented. Together, there were 43 adult and 12 pediatric patients with 13 different tumor types, including salivary gland tumor, sarcoma, infantile fibrosarcoma, lung, thyroid, colon, and melanoma, all with TRK fusions in their tumors.

Among the 46 evaluable patients who received larotrectinib, the objective response rate (ORR) was 78 percent, with responses in 12 tumor types. One responder continued to receive treatment at 23 months, eight patients had responses for 12 months or longer, while 16 patients had responses for more than six months.

“Larotrectinib could be the first targeted therapy developed in a tissue type-agnostic manner, and the first developed simultaneously in adults and pediatrics,” the presenters noted in their abstract. The therapy was well tolerated, and the most frequently observed side effects were fatigue, dizziness, and nausea, according to the lead researcher, David M. Hyman, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who presented the study at the conference.

The manufacturer of larotrectinib, Loxo Oncology, is expected to submit an application to the FDA later this year or in early 2018.

“This is an extraordinary result,” said George Demetri, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, director of the Ludwig Center at Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, and director of the Center for Sarcoma and Bone Oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in a Forbes interview. “Lots of doctors don’t realize there’s a possibility that their patients might have this genetic change. They don’t screen for TRK mutations, so 9 in 10 cancer patients who might benefit from this drug likely don’t have the opportunity to try it.”

Progress with larotrectinib is along the lines of Demetri’s prediction in a post to forecast cancer therapy advances in 2017. In an interview for that post, he said it is good news that we are “still uncovering virtually monogenic diseases—diseases that are driven by single oncogenic fusions or mutations,” referring to NTRK fusions. Therapies targeting single mutations, such as NTRK fusions, lead to durable and dramatic responses, added Demetri, who is a board member of the AACR. He also recognized the fact that most patients treated with targeted therapies develop resistance, but added that he is hopeful that the cancer research community will find new solutions to finding cures.

Next-generation TRK inhibitor, LOXO-195, effective in patients with acquired resistance to larotrectinib

In addition to the presentation at the ASCO conference, Hyman and colleagues simultaneously published a study in the AACR’s journal Cancer Discovery, in which they tested a next-generation TRK inhibitor, LOXO-195, in two patients who acquired resistance to larotrectinib: a 55-year-old woman with heavily pretreated advanced LMNA-NTRK1 fusion-positive colorectal cancer who had a partial response to larotrectinib but progressed after six months of treatment, and a 2-year-old girl with an ETV6-NTRK3 fusion-positive recurrent infantile fibrosarcoma of the right neck and base of skull whose tumor regressed with larotrectinib treatment but developed resistance via the TRKC G623R mutation.

Upon treatment with LOXO-195, both patients had rapid tumor responses, and treatment extended the overall duration of disease control. The authors of the study note that the data establish LOXO-195 as a sequential therapy in patients whose tumors have TRK fusions and develop acquired resistance to larotrectinib.

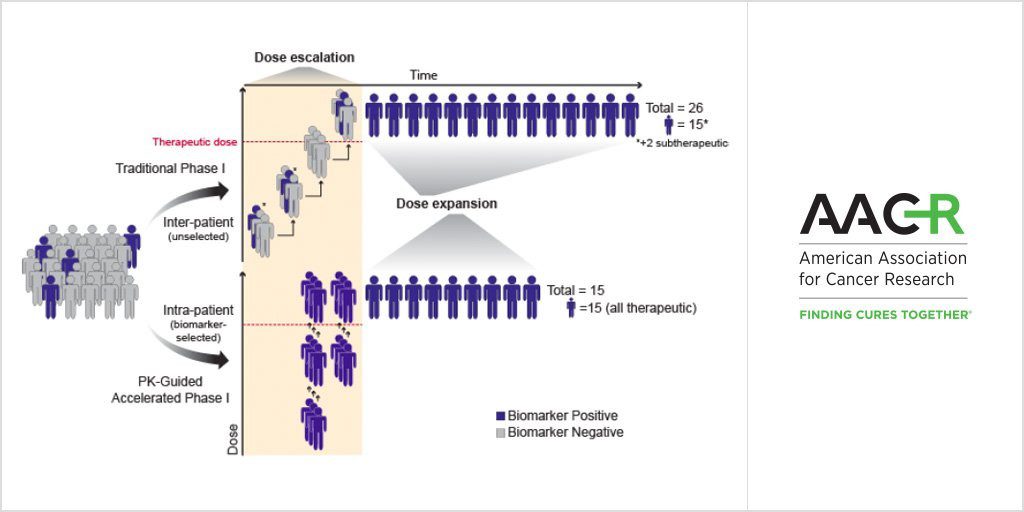

New clinical trial design with a “real-time clinical development” approach is the way forward

Researchers propose a new trial design that is appropriate for highly selective agents against clearly validated targets.

A unique feature of this study is that LOXO-195 was developed and tested in patients who were recruited to a clinical trial designed to validate the preceding TRK inhibitor, larotrectinib. The authors note that they accomplished this by performing rapid preclinical testing and toxicology studies, and by utilizing the FDA’s expanded access (compassionate use) program.

Moving forward, the authors propose a clinical trial design with a “personalized, real-time clinical development strategy” involving fewer, biomarker-selected patients who can receive sequential experimental therapies once enrolled, which is not possible through traditional phase I trial designs. Such a strategy is likely to be more appropriate for “highly selective agents against clearly validated targets,” the authors note.