The Unequal Geographic Burden of Lung Cancer

The lung cancer death rate—the number of lung cancer deaths per 100,000 U.S. men and women—has been decreasing slowly but steadily in the United States for the past 25 years. The latest National Cancer Institute (NCI) data show that it declined 31 percent from a high of 59.1 lung cancer deaths per 100,000 U.S. men and women in 1993 to 40.6 in 2015.

Lung cancer is associated with a vast stromal desmoplastic reaction in which the connective tissue, associated with the tumor, thickens similarly to scars. Image courtesy of the National Cancer Institute.

Despite the progress, lung cancer remains the leading cause of death from cancer in the United States, with more than 154,000 U.S. men and women expected to die from the disease in 2018 alone. Eighty percent of these deaths are attributable to cigarette smoking.

These overall statistics are grim reading. However, they do not paint a complete picture because the burden of lung cancer is not shared equally among all segments of the U.S. population. This is predominantly a result of disparities in cigarette smoking rates. That’s why November, which is Lung Cancer Awareness Month, is a good time to highlight the dangers of cigarette smoking. And it is especially important to discuss the urgent need to overcome lung cancer health disparities.

The dangers of cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking can cause not only lung cancer, but also 17 other types of cancer and numerous other chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and respiratory diseases. In addition, many of these negative health effects can be caused by exposure to secondhand smoke and the use of tobacco products other than cigarettes—including cigars, pipe tobacco, smokeless tobacco products (e.g., chewing tobacco and snuff), and waterpipes.

To prevent more smoking-related cancers, we must reduce cigarette smoking rates and exposure to secondhand smoke. To do this, we must more completely understand which segments of the U.S. population shoulder the largest burden of lung cancer and cigarette smoking because this knowledge will allow us to develop and implement tobacco-control strategies tailored to these individuals.

Disparities in lung cancer and cigarette smoking

Many studies have shown that there are substantial racial and ethnic disparities in the burden of lung cancer and cigarette smoking in the United States. For example, non-Hispanic black men have the highest lung cancer incidence and death rates among all racial and ethnic groups; these rates are 16 percent and 19 percent higher, respectively, than the rates for non-Hispanic white men, which are the group with the second highest burden of lung cancer. The cigarette smoking rate is also higher among non-Hispanic black men than it is among non-Hispanic white men—20 percent versus 18 percent.

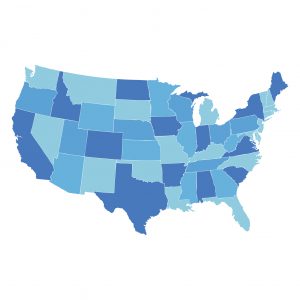

There are also geographic differences in the burden of lung cancer, as highlighted by two recent papers published in American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) journals. The first of these papers, which was published in March 2018 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, showed that from 1990-1999 to 2006-2015, lung cancer death rates among women rose by 13 percent in a region covering central Appalachia and southern parts of the Midwest. During the same period, in a second region encompassing northern parts of the Midwest, lung cancer death rates among women rose by 7 percent. In the remainder of the contiguous United States, lung cancer death rates among women fell by 6 percent.

The lead author of the study, Katherine Ross, MPH, said, “We know that Midwestern and Appalachian states have the highest prevalence of smoking among women and the lowest percent declines in smoking in recent years, so it is perhaps not surprising that we found that women in these areas experienced a disparity in lung cancer death rates.”

The second paper, which was published in Cancer Prevention Research in October 2018, reported that California is at the opposite end of the spectrum of lung cancer burden. The data show that from 1986 to 2013 the lung cancer rate decreased more rapidly in California than in the rest of the United States. By 2013, it was 28 percent lower in California than in the rest of the country.

Alongside the reduction in lung cancer death rates, the researchers found that the percentage of those ages 18 to 34 who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their life declined twice as fast in California compared to the rest of the United States from 1974 to 2000. By 2014, 40 percent fewer adults in this age range reported ever smoking 100 or more cigarettes in their life in California compared with the rest of the country (18.6 percent versus 31.4 percent).

In both studies, the authors emphasize that cigarette smoking rates are tied to the relative stringency of the local tobacco control policies. “There are several effective tobacco control policies available, such as increased excise taxes on tobacco and comprehensive smoke-free air laws that ban smoking in the workplace, restaurants, and bars,” said Ross. “However, many states in our identified hot spots [Midwestern and Appalachian states] either do not have these measures in place, or they are comparatively weak and could be strengthened.” Conversely, the authors of the Cancer Prevention Research paper state that “California led the rest of the United States in implementing tobacco control, including increasing the cigarette tax every decade through 1999.”

Together, the two studies highlight how the development and implementation of tobacco-control strategies in different geographic regions has influenced cigarette smoking rates and, therefore, lung cancer death rates. They also identify regions and populations where additional tobacco-control strategies are needed if we are to prevent more smoking-related cancers.