Understanding Risk and Improving Treatment for Testicular Cancer

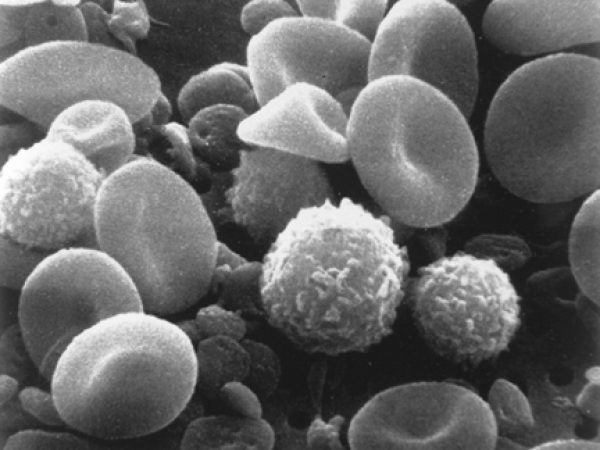

Testicular cancer forms when cancerous cells develop in one or both testicles. Almost all cases of the disease begin in the germ cells of the testicles, which are responsible for producing immature sperm. The two main types of testicular cancer are seminomas and nonseminomas, with nonseminomas typically being more aggressive.

Testicular cancer is relatively uncommon, expected to account for about 0.5 percent of new cancer cases in 2020 in the United States, although incidence rates appear to be rising in many countries, including the United States.

Fortunately, this disease has a relatively good prognosis: The relative five-year survival rate is approximately 95 percent.

Who is at risk for testicular cancer?

While the exact cause of testicular cancer is unknown, several factors may be associated with an increased risk. Individuals with an undescended testis or a family or personal history of testicular cancer may have a higher risk for the disease. Certain genetic variants may also be associated with the development of testicular cancer, as described in a commentary published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). Additionally, neonatal exposure to high levels of the hormone androstenedione were found to be associated with the development of testicular cancer during adolescence in a study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, another AACR journal.

About half of all cases are in men who are between 20 and 34 years of age. Testicular cancer is most common among non-Hispanic white men; however, another study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention suggests that the incidence rates in other races may be increasing.

In this study, the authors, Armen Ghazarian, PhD, MPH, and Katherine McGlynn, PhD, MPH, examined testicular cancer incidence data from 51 registries covering cases from the years 2001 through 2016 and from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. While testicular cancer incidence rates remained highest for non-Hispanic white men, the authors found that Asian/Pacific Islander men experienced the greatest increase in incidence rate during this period, with an annual percent change of 2.47. Asian/Pacific Islander men had the greatest increase in incidence rate for nonseminomas, while American Indian/American Native men had the greatest increase in incidence rate for seminomas.

“I hope the results from this study will increase awareness of TGCT among men of all racial/ethnic groups,” said McGlynn. “While incidence remains highest among non-Hispanic white men, it is becoming increasingly clear that this disease does not just affect men of European ancestry.”

How is testicular cancer treated?

Testicular cancer may be treated by surgery to remove the affected testicle (a procedure known as an inguinal orchiectomy) and any affected lymph nodes or metastatic tumors. Some patients may also receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any remaining cancer cells.

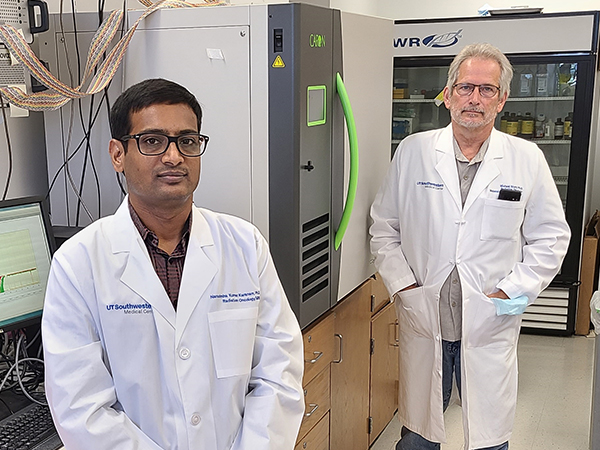

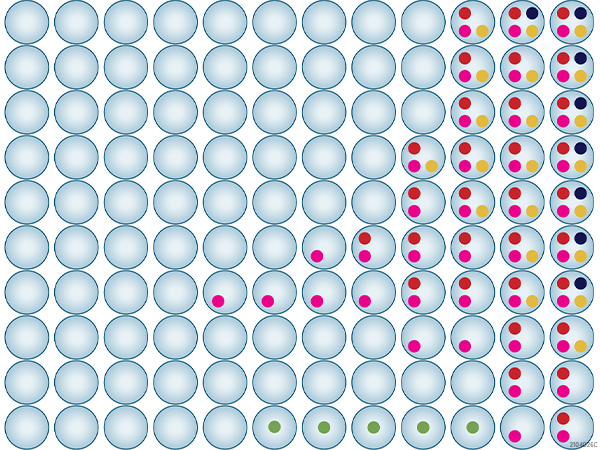

Standard chemotherapy regimens for testicular cancer commonly include the DNA-damaging agent cisplatin. While over 80 percent of metastatic testicular cancers respond to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, some testicular cancers are resistant to this treatment. A recent preclinical study published in Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, an AACR journal, suggested that inhibition of certain cellular proteins may help sensitize resistant testicular cancer cells. In this study, Steven de Jong, PhD, and colleagues tested several chemical inhibitors in combination with cisplatin to determine their impact on testicular cancer cell viability. De Jong and colleagues found that inhibition of the mTORC1/2 proteins significantly reduced viability of testicular cancer cells and sensitized cisplatin-resistant cells and patient xenografts to cisplatin treatment.

“Testicular cancer patients with relapsed or refractory disease have a poor clinical outcome, and different investigational chemotherapy regimens have not improved survival of these patients,” said de Jong. “Our findings demonstrated that mTORC1/2 can potentiate cisplatin treatment, and this combination therapy might be an effective therapeutic option for patients with metastatic testicular cancer who are refractory to standard treatment.”

Surviving testicular cancer

While most cases of testicular cancer are highly treatable, it is important to acknowledge the long-term effects of treatment that survivors may face, especially since testicular cancer is typically diagnosed in younger men. Radiation therapy can lead to secondary cancers, for example, and both chemotherapy and radiation therapy have been associated with fertility problems. Furthermore, two studies published in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the AACR, suggested that cisplatin can persist in patients for many years after treatment, leading to long-lasting adverse effects, such as tinnitus, in certain populations.

Continued efforts to understand risk factors, improve treatments, and reduce long-term adverse effects will be crucial to improve prevention and treatment of this disease, while also maintaining a high quality of life for survivors.

I found this article on testicular cancer to be very helpful and informative. It provides a clear and concise overview of the disease, its causes, and its treatment of testicular cancer. Overall, this is a great resource for anyone seeking information on testicular cancer.