AACR Forum on Brain Cancer Highlights A Glimmer of Progress and Calls for Further Collaboration

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was dominating the headlines, but CNN reporter Andrew Kaczynski was happy at home. He and his wife had a new baby girl, Francesca, who appeared to be thriving.

Francesca became ill one September night, and a hospital visit led to a shocking diagnosis: an atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, a rare type of brain cancer that affects 50 to 60 children per year in the United States.

After months of intensive chemotherapy and multiple surgeries, Francesca died on Christmas Eve. She was only 9 months old.

Since then, Kaczynski and his wife, Rachel Ensign, have become parents to another little girl, Talia. They have also immersed themselves in patient advocacy and fundraising. Leading a group called Team Beans, after Francesca’s nickname, they have raised $2.5 million to fund brain cancer research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where Francesca was treated.

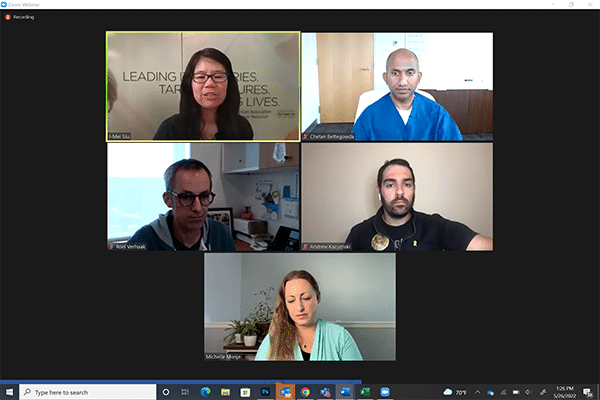

On Thursday, Kaczynski joined a panel convened by the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) titled Brainstorming for Brain Tumor Cures. The panel was a joint venture between AACR journal Cancer Discovery and the AACR’s Science Policy and Government Affairs office.

“So many of the AACR’s policy priorities and initiatives are science-based. This partnership with Cancer Discovery will allow us to use the scientific advances they publish to advocate for policies that support lifesaving cancer research,” said Jon Retzlaff, the AACR’s chief policy officer and vice president of science policy and government affairs.

The panel, convened as part of Brain Cancer Awareness Month, included Chetan Bettegowda, MD, PhD, professor of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine; Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and pediatric neuro-oncologist at Stanford University; and Roel Verhaak, PhD, professor and associate director of computational biology at the Jackson Laboratory. “Our panelists all represent different ways of developing therapies for these devastating cancers,” noted I-Mei Siu, PhD, senior editor of Cancer Discovery and the moderator of the panel.

Brain cancer is a rare diagnosis, with about 25,000 cases diagnosed each year in the United States.

There are multiple types of brain cancer, making each specific diagnosis an even smaller part of the overall population. But as Monje said, “When it’s affecting your family, it doesn’t feel rare at all.”

At Stanford, Monje runs a clinical trial of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). This type of brain cancer is exceedingly rare, with fewer than 400 diagnoses per year in the United States. The patients are almost always children, and most live for less than two years after they are diagnosed.

During Thursday’s program, Monje shared details about a study presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2022 that provided a glimmer of hope that CAR T-cell therapy—the groundbreaking advance that has produced complete remission in thousands of blood cancer patients—may someday be used to treat brain tumors.

Monje explained that through research on tumor tissue donated by patients’ families, researchers identified the GD2 protein as a potential target for T-cell therapy. Stanford colleagues including Crystal Mackall, MD, FAACR, began testing the therapy in patients with DIPG and another type of cancer, spinal cord diffuse midline glioma.

At the Annual Meeting, Monje’s colleague Robbie G. Majzner, MD, reported that in a phase I dose-escalation study of the GD2 CAR T-cell therapy, nine out of 10 evaluable patients demonstrated clinical benefit, including near-complete responses from one patient with spinal cord diffuse midline glioma and one patient with DIPG. This story was covered by USA Today.

“I am truly hopeful right now, having seen some therapeutic benefit, but cognizant that there is still a lot of work to do,” Monje shared on Thursday.

Brain cancer has some unique characteristics that make it difficult to treat, the panelists agreed. First, Verhaak said, brain cancer has a high degree of intratumoral heterogeneity. “You try to hit the tumor in one spot, and it pops up somewhere else,” he said.

Furthermore, Verhaak noted, brain tumors grow in an “immune-privileged location.” Researchers have long been frustrated by the fact that the body’s immune system does not appear to recognize brain tumor cells in the way it can recognize other cancers.

Brain cancer treatment becomes exceptionally challenging as physicians try to treat tumors while preserving brain function, the panelists agreed. With a high degree of danger in every surgery, noninvasive procedures would greatly benefit patients. To that end, Bettegowda described a clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that is evaluating the use of liquid biopsies to monitor longitudinal changes during treatment for glioblastoma.

“This could allow us to study patients in a way that hasn’t before been possible,” he said. “We hope that this will lead us to new discoveries that will lead to future clinical trials and ideally, improved therapeutics for patients with this cancer type.”

The panelists said that to accelerate progress against brain cancer, there must be more cooperation between academic institutions and government agencies. Several initiatives are underway, such as the National Cancer Institute’s NCI-CONNECT (Comprehensive Oncology Network Evaluating Rare CNS Tumors) program, which studies rare central nervous system tumors and aims to establish partnerships in the field, and the GLASS Consortium (Glioma Longitudinal Analysis), which provides a publicly accessible database on the genetic makeup of brain tumors.

Since his daughter’s death, Kaczynski has become a powerful advocate for increased funding for brain cancer research. Due to the relative rarity of brain tumors in children, he and others believe there is little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs to treat these cancers.

“It was disheartening to learn how much work there is to be done. But it’s also motivated me to fundraise. I want to build a legacy for my daughter,” he said, through funding the brilliant work of cancer researchers and oncologists.

To learn more about brain cancer, see this collection of articles from AACR journals.