Two Years of Cancer Research Communications: A Conversation with the Journal’s Editors-in-Chief

In 2021, Lillian L. Siu, MD, and Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, FAACR, each received a call from AACR Chief Executive Officer Margaret Foti, PhD, MD (hc), asking if they’d be interested in serving as the inaugural co-editors-in-chief of Cancer Research Communications, the organization’s first open-access journal.

“I was, of course, flattered,” said Siu, who is an oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and a clinician-scientist at the University of Toronto. “I thought it made perfect sense for AACR to have an open access journal. Knowing that it would be alongside Elaine Mardis made it even more compelling, so I gladly agreed.”

Mardis also jumped at the opportunity.

“I’ve always had a strong commitment to open-access publishing, so I was really delighted to get the call asking about my interest and hearing that Lillian Siu, whom I’ve always held in very, very high regard, would also be invited to be a co-editor-in-chief,” said Mardis, who is co-executive director of the Institute for Genomic Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, a professor of pediatrics at The Ohio State University, and an AACR Past President.

Together, the pair have led Cancer Research Communications through its first two years of submissions, reviews, and publications, helping define the journal’s editorial ethos and place in the AACR portfolio of peer-reviewed journals. Under their leadership, the journal has published over 300 articles to date.

As Cancer Research Communications wrapped up its second year, Mardis and Siu offered their perspectives on the journal’s mission and top publications to date.

How does Cancer Research Communications differ from other AACR journals and other cancer research journals in general?

Mardis: One clear area of distinction that we planned from the very beginning was the breadth of the journal. Cancer research encompasses multiple areas of expertise. It’s very interdisciplinary, so we wanted to capture that breadth in the content we publish. Beyond diverse research topics, we also have breadth in terms of the types of cancer research—everything from basic to clinical science plus correlative science coming out of clinical trials. It’s truly bench to bedside and back.

The other thing that distinguishes Cancer Research Communications from other journals of its type is that we have within our guidelines some unique aspects that I haven’t seen in other journals. For example, we’re interested in manuscripts that reproduce others’ results with different materials and experimental approaches.

Siu: I would say that in addition to the breadth of research we publish, another feature that sets us apart is that we’re interested in the kind of papers that do not necessarily go from beginning to end and address everything in a nice package. Perhaps they leave some questions for others to help fill in over time, but they have the scientific quality that is worthy of an AACR journal. We understand that it is not always possible to deliver a complete story in one manuscript.

Obviously, if a researcher thinks that additional experiments are achievable in a reasonable time and they’re ready to tackle them, then by all means, they should finish everything that they can and submit their study to a journal such as Cancer Discovery.

But if they think it would take a lot more time, resources, or infrastructure to tie up all the loose ends, and the results as they stand are interesting enough for others to be aware of and build upon, I think Cancer Research Communications would be a very good fit for it, assuming, of course, that the analyses and methods are sound.

Similarly, for negative studies or studies with small sample sizes, if the results answer a question that people have been asking repeatedly, we would consider publishing it. For these studies, the discussion section will be key for researchers to state the limitations and to put their findings into context for readers who are outside their field.

Can you highlight a few studies from the past two years that exemplify the journal’s niche?

Mardis: There are three studies that I think illustrate the breadth of inquiry that Cancer Research Communications supports, with the first uncovering basic features of tumor biology, the second having implications for clinical research, and the third using data science to understand clinical outcomes.

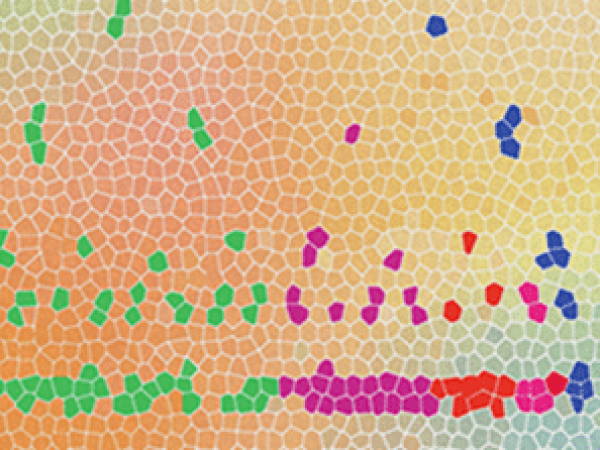

In the first study, researchers employed cutting-edge technologies, such as single-cell RNA-seq, CITE-seq, and mass cytometry, to examine the immune microenvironment in multiple myeloma. The novelty of their approach is that they looked at the intersectionality between all three types of data. This approach may be especially significant in multiple myeloma where we don’t fully understand how the immune microenvironment contributes to disease progression. This paper defined some of the markers in the immune microenvironment that were associated with rapid progression in multiple myeloma patients and also highlighted key differences between these three cutting-edge technologies in terms of how they “perceive” differences in gene expression between cells in a tumor.

Another study examined genomic heterogeneity across 42 different tissue and blood samples from a single patient with a metastatic pulmonary atypical carcinoid. The main finding was that genetic variants that were shared across different metastatic sites could be detected in circulating tumor DNA, but emerging variants were not always detectable. Even though this study examined samples from just one patient, the finding has important implications. If we want to utilize circulating tumor DNA to study cancer evolution or monitor patient outcomes, we must recognize that there’s a level of sensitivity that we will have to transcend before we can detect emerging variants, which are often the ones that we most want to identify.

The last paper I want to mention examined sex-specific differences in brain tumors. This was a paper looking at these very specific differences between male and female patients with TP53-mutated brain cancer. The researchers found differential gain of function activity across groups and illustrated with a nice set of data the importance of sex as a biological variable, which I think often gets overlooked.

Siu: I’ll also highlight the study Dr. Mardis mentioned that sequenced samples from a single patient with a metastatic pulmonary atypical carcinoid. While this study only examined one patient, the authors went above and beyond a simple case report to conduct a very in-depth examination with multiregional sampling to provide valuable insights into how tumors evolve and metastasize. I think that’s something that sets this study apart.

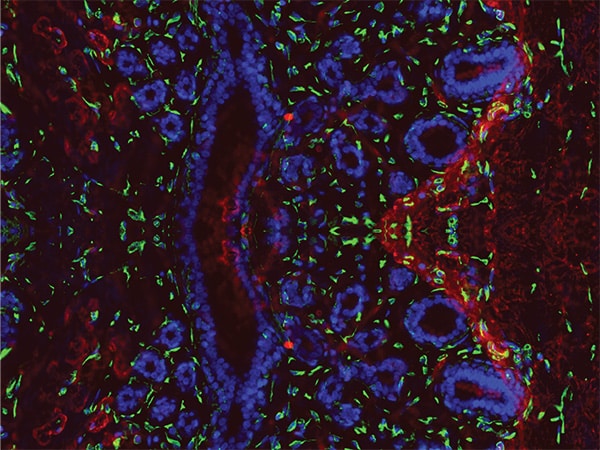

In another paper that I would say exemplifies our niche, researchers performed a comprehensive immune profiling of localized leukoplakia (precancer changes in the oral cavity) with the goal of understanding the immune landscape of these lesions. We don’t have a lot of data in this area because patients with these precancer lesions are typically seen by dentists, rather than in cancer centers.

These types of data may help us understand how these lesions progress to cancer, uncover how to prevent this progression, or determine if the resulting tumors might be susceptible to immune checkpoint inhibition, for example. Moreover, this study sets the stage for others to perform similar types of analyses for precancer lesions at other sites, not just in the oral cavity.

Another study I would highlight examined the effect of combining an EXO1 inhibitor, which is a nuclear transport inhibitor, with a KRAS G12C inhibitor in KRAS G12C-mutated tumor models. Responses to clinically approved KRAS G12C inhibitors tend to be fairly short-lived, and there’s a lot of interest in learning how to deepen responses. Having preclinical models to interrogate different combinations will help researchers discover ways to prolong the efficacy of these drugs in the clinic. Manuscripts reporting on preclinical models that explore and inform clinical evaluations would fit the types of articles we are looking for, especially if new and improved models are used to address a research question that is not addressable with current existent models.

What is your vision for the next two years—and beyond—of Cancer Research Communications?

Mardis: I would like to see us review and publish more research in the field of data science and how it impacts cancer research and clinical trials. Another area in which I’d love to see us grow is novel experimental models. There’s been a lot of skepticism of late around mouse models in particular and whether they’re reflective of human cancers. In response to that, there have been a number of efforts—some of which I’m aware of, many more of which I’m probably not—around patient-derived model systems.

We need to think outside the box to create model systems that don’t require years of careful breeding and genetic engineering to produce. I think organoid systems and tumoroid systems have started to fill that void, but we need to keep pushing the envelope. There has also been a lot of interest around tissue slice cultures to examine tumor growth kinetics and genetics in tandem with therapeutic responses. I would like to see us review and publish more of these studies.

Siu: Well, first and foremost, we want more people to submit their papers to us, and we want more researchers to serve as reviewers. We have published over 300 papers in two years, which I think is impressive for a new journal, but we would like to grow even more.

While we are proud to cover a range of article types, at the same time, I think it would be good for us to be remembered for something that sets us apart from other journals out there. In particular, I’d like to us be known as the journal that publishes studies that make perhaps incremental changes but changes that are important nonetheless because they lead to more questions and stimulate other areas of research.

I think that is an important goal for us to achieve—to be a catalyst for the next big discovery.