Dosing, Surgery, and Treatment Resistance—Seeking New Options for Kidney Cancer

What happens when a cancer treatment is no longer effective for a patient because of drug resistance? Or when too many side effects make a treatment too difficult to continue? Or when age-related risk factors make certain treatment options, such as surgery, unsafe for some patients? While these questions are not limited to those dealing with kidney cancer, recent studies examining various treatment options for the seventh most common cancer in the United States may help lead to better answers and more effective solutions.

A Search for the Path of Least Resistance

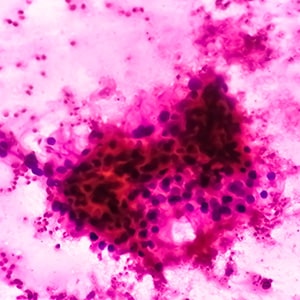

Over the past 20 years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several treatment options for renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which accounts for an estimated 90% of cancers in the kidney. A substantial number of patients, however, fail to see an effect at the outset of therapy or develop resistance to standard treatments such as vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGF TKIs) or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

In a study published in Cancer Research, a group of researchers attempted to identify therapies that are more likely to be effective in circumventing the limitations with current approaches. They selected 10 drugs based on certain criteria and tested them in six xenograft models. (Xenografts are made by implanting human tissue from patients affected by a disease, in this case RCC, into laboratory mice.)

The drugs selected were: abemaciclib, beta-hydroxybutyrate, selumetinib, and losartan (because they were being investigated in RCC clinical trials at the time of this study); acriflavine hydrochloride and birinapant (both had showed enhanced efficacy when combined with another targeted agent even though they hadn’t been tested in RCC); panobinostat and sapanisertib (previously tested as monotherapies for RCC but failed to show a strong response); and cabozantinib and sunitinib (already approved RCC treatments that the researchers wanted to test as combination therapies).

Ultimately, the researchers found that a combination of sapanisertib and cabozantinib was the most effective option. This pairing resulted in a significantly lower average relative tumor volume (RTV) in five of the six models when compared to the control mice after one month. The combination also resulted in lower average RTV compared to the use of either sapanisertib or cabozantinib alone. Further, the researchers found this combination was effective in the xenograft model derived from a patient whose cancer relapsed after taking other TKIs and ICIs. Given these results, the researchers suggest this combination be explored further in human trials.

Many other studies are also examining different ways to overcome treatment resistance in RCC patients. And recently, the FDA expanded the approved indication for belzutifan to include patients with advanced RCC that has progressed after treatment with an anti-PD-1/PD-L-1 ICI therapy and a VEGF inhibitor. The FDA also recently granted Fast Track Designation, which helps to accelerate the approval review process, to a CAR-T cell immunotherapy that targets HLA-G positive locally advanced or metastatic clear cell RCC in patients who did not respond to or have grown intolerant to certain RCC treatment options. The treatment candidate is in a phase I/IIa trial (NCT05672459).

Putting Some Distance in Drug Duo Dosage

Resistance to treatment is also an issue with the combination of ipilimumab with nivolumab for intermediate- or poor-risk advanced RCC, which about 20% of patients develop, but researchers wanted to explore another problem that forces some patients to stop the use of these therapies—treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). Adverse events, which patients may more commonly refer to as side effects, are graded on a severity level of 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe), 4 (life-threatening or disabling), or 5 (death). In the Checkmate 214 trial, which served as the basis for this combination therapy’s approval in 2018, the therapy showed significantly improved overall survival rates compared to the RCC treatment sunitinib; however, 46% of patients experienced a grade 3 or 4 TRAE and, as a result, 22% discontinued treatment.

Since then, increasing the dosing interval of ipilimumab has been found to lead to fewer TRAEs during the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer and metastatic melanoma. Researchers wanted to test whether the same would be true in the case of advanced RCC. In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, they randomly assigned participants to two different treatment schedules as part of the phase II PRISM trial.

The 64 patients put on the standard schedule received 3 mg/kg of nivolumab plus 1 mg/kg ipilimumab once every three weeks with 480 mg of nivolumab also given once every four weeks. The 128 patients on the modified schedule received the same dosage of the combination therapy, but once every 12 weeks instead. Additionally, they received the single-agent 240 mg nivolumab once every two weeks between the first and second combination doses, and then 480 mg once every four weeks between the rest of the combination doses.

Within the first year of treatment, 53% of those on the standard schedule experienced a grade 3 or 4 TRAE and 39% discontinued treatment as a result, compared to 33% of patients on the modified schedule reporting a grade 3 or 4 TRAE and 23% discontinuing treatment. Despite the change in dosing schedules, median overall survival and progression-free survival were similar in both cohorts.

The authors state that the results of this trial, as well as previous studies examining ipilimumab, suggest spreading out the dosing interval to reduce toxicity without compromising efficacy.

When Surgery Is Not an Option

As the rate of kidney cancer increased between 2006 and 2016, the highest growth was seen in those between 70 and 79 years old, according to a study published in Translational Andrology and Urology. This can be an issue as those over 70 might not have as many treatment options. Surgery, for one, might be off the table for some elderly patients who may have other medical issues (such as high blood pressure or diabetes) or complications that could lead to dialysis. That is why researchers, who presented a study at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Annual Meeting in October 2023, examined the use of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), which is also known as stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy.

With SBRT, a high dose of radiation is targeted at the tumor site to limit the impact on surrounding organs. As part of the FASTRACK II phase II clinical trial, the researchers tested the use of SBRT in 70 patients with a median age of 77 who were either diagnosed with inoperable kidney tumors or declined surgery. The participants were treated with one or three sessions of SBRT depending on the size of their tumor.

After a median follow-up of 42 months, no patients had died as a result of their cancer, and none saw their tumors progress beyond where they started. Meanwhile, overall survival was at 99% after one year and 82% after three years. Further, 16% of patients did not experience any adverse events and 10% experienced a grade 3 event, which was the highest level of adverse event recorded in the study.

The researchers stated that these results support the design of a future randomized trial comparing the use of SBRT to surgery to see if this can be an option for more patients with inoperable kidney tumors.