Key Considerations for Improving Dosage Optimization in Oncology

Cancer patients are now living longer and more fulfilling lives, as illustrated by the U.S. cancer death rate dropping 34% between 1991 and 2023 and the continued survivorship of more than 18 million individuals in the United States with a history of cancer. These improvements have been precipitated in no small part thanks to innovations in cancer therapeutics, as new cutting-edge drugs that target specific characteristics of a patient’s tumor are generating transformational improvements in patient outcomes.

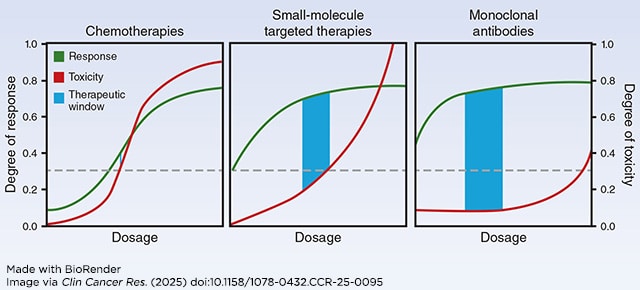

But as drug development programs have shifted to a focus on targeted therapies and immunotherapies, not all aspects of the clinical research process have kept up with this revolution. Most first-in-human (FIH) clinical trials in oncology, which seek to identify safe and potentially effective doses for new drugs, still use a protocol that was introduced in the 1940s and formalized in the 1980s known as the 3+3 design. This approach was created with chemotherapeutics—the prominent anticancer drugs of that time—in mind. In this approach, small cohorts of patients are treated over short courses with escalating doses of drug until a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is reached, where only 1 in 6 patients across two cohorts of three experience an intolerable side effect known as a dose-limiting toxicity. This MTD is typically advanced in subsequent trials and becomes the recommended dose.

Unfortunately, studies have shown that this dose is often poorly optimized. According to one report, nearly 50% of patients enrolled in late-stage trials of small molecule targeted therapies required dose reductions due to intolerable side effects. Further, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has required additional studies to re-evaluate the dosing of over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs. These issues stem from the fact that the 3+3 design doesn’t factor in whether a drug is effective at treating cancer, doesn’t represent the much longer treatment courses patients typically undergo in late-stage trials or clinical care settings with modern drugs, doesn’t correspond with how newer therapeutics work (see figure below), and is even poor at identifying MTD, potentially leading to dosages that are too high and cause unnecessary toxicities. As a result, patient advocates have begun calling for revisions to the traditional MTD-based dosing paradigm.

Ongoing Reform in Dosage Selection and Optimization

These issues were the catalyst behind the FDA’s recent efforts to reform dosage selection and optimization. In 2021, the FDA launched Project Optimus to encourage educational, innovative, and collaborative efforts towards the selection of dosages for oncology drugs that maximize both safety and efficacy. Other FDA efforts have included various programs that outline best practices for drug development and increase communication with industry partners, including a 2024 guidance document and programs such as the Model-Informed Drug Development Paired Meeting Program and the Fit-for-Purpose Initiative.

Continuing this push, the FDA and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) convened a workshop in February 2024 that gathered stakeholders from industry, academia, government, and patient advocacy groups to discuss ways to make progress in oncology dosing optimization. This workshop inspired a three-article series, recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, that summarizes important considerations for dosing optimization across different stages of drug development.

How to Select Doses for First-in-human Trials

The first article in the series examines how to select dose ranges for evaluation in FIH trials, as well as how to design trials that provide patients with the best benefit-risk ratio possible at early stages when very little is known about the investigational drug being studied. Traditional methods for identifying FIH doses primarily center on scaling drug activity data derived from animal models to humans based on weight and then reducing the dose by a safety factor. This approach errs on the side of safety, preventing adverse effects but also decreasing the chance of seeing drug activity.

However, humans and animal models have obvious differences aside from size. Most modern cancer therapeutics bind to receptors—molecules on cancer cell surfaces that send pro-cancer signals—and inhibit them, directly preventing cancer growth or enabling the immune system to attack the cancer. Receptors in humans and animal models are inherently different. While most novel therapeutics fight cancer in animal models, physical differences in the receptors or differences in the amount of receptors present can lead to different receptor occupancy rates between humans and animal models, which is a critical factor to determine if a drug will have on-target anticancer effects versus off-target effects that might cause side effects. These discrepancies have led to the adoption of mathematical models that consider a wider variety of factors to determine starting doses, which have shown success in recommending higher starting doses that could provide more patient benefit.

Once potential doses have been selected, they must be tested to confirm the anticancer effects predicted by modelling. A variety of novel FIH dose-escalation trial designs to test multiple doses have been developed that also utilize mathematical modeling approaches instead of the traditional algorithmic 3+3 approach. These approaches can result in more nuanced dose-escalation/de-escalation decision-making by responding to efficacy measures and late-onset toxicities as well as based on the outcomes of the last incorporated patient or cohort. Unfortunately, these designs are still not frequently used due to their relative complexity—although some of these approaches now have apps and software packages that make them simpler to understand and utilize than ever before.

How to Select Doses for Further Exploration

However, these modeling-informed FIH trials are not designed to provide a deep understanding of a drug’s biological activities, rather to provide potentially useful dosages for further study. To support the collection of additional information, the FDA recently finalized a guidance outlining that in order to recommend a specific dosage for FDA approval, drug sponsors should directly compare multiple dosages in a trial designed to assess antitumor activity, safety, and tolerability. While this could be done in a large registrational trial, which seeks to definitively evaluate the benefit/risk of the intervention at hand in a large population in order to support potential FDA approval, it is more prudent from a financial and sample-size standpoint to fulfill this requirement in a smaller trial.

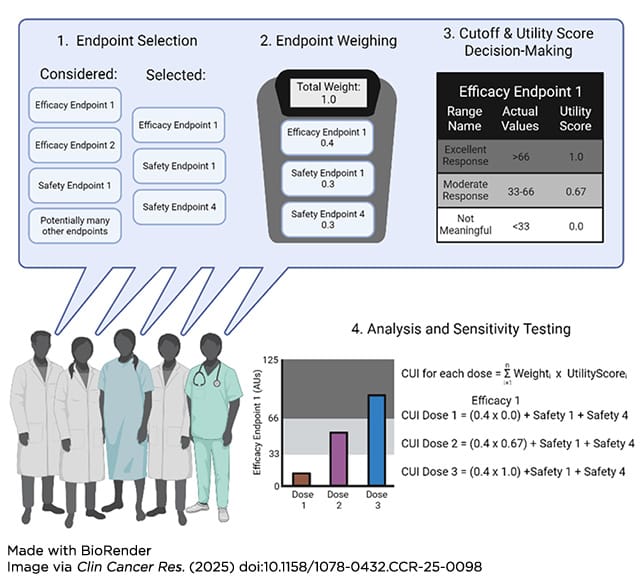

Selecting the doses to compare in this proof-of-concept trial can be difficult, and is the focus of the second article. Again, novel trial design features and mathematical modeling techniques have been developed to aid investigators in making this critical selection. For example, the addition of biomarker testing, such as measuring changes in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels, can help identify responses not detected due to short follow-up. While not all biomarkers may be thoroughly validated from a regulatory standpoint, they can still be part of the amalgamation of data that provides a rationale for selection.

Additionally, backfill and expansion cohorts, which increase the number of patients at certain dose levels of interest within early-stage trials, can provide more clinical information that strengthens the understanding of the benefit/risk ratio of a particular dose level. Once all relevant data have been collected, frameworks such as clinical utility indices (CUI) can provide a quantitative and collaborative mechanism to integrate the data and determine concrete doses of interest (see figure below).

Making the Final Dosage Decision

After this deeper evaluation of multiple doses, a final decision must be made. This final dose will be used in a large registrational trial that definitively evaluates the benefit/risk of the intervention at hand in a large population in order to support potential FDA approval. The third manuscript focuses on this final dosage decision. Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic, exposure-response, and quantitative systems pharmacology models are among the techniques that can be used at this stage to help identify optimized dosages from the larger clinical datasets collected up to this point. Critically, such approaches can combine evaluation of both safety and efficacy, extrapolate the effects of doses and dose schedules not clinically tested, and address confounding factors such as concomitant therapies.

Considerations for the use of seamless clinical trial designs were also highlighted in this paper. In traditional oncology drug development, there are separate trials for distinct stages of development—FIH, proof-of-concept, and registrational. Adaptive trials combine these various phases, allowing for more rapid enrollment, faster decision-making, and, in certain designs, the potential to follow patients across two traditionally distinct phases. This allows for the accumulation of more long-term safety and efficacy data to better inform dosing decisions while also using lower sample sizes.

Toward More Optimized Dosing

A common thread across all three articles is the need to generate and utilize as much data as possible, instead of relying primarily on short-term toxicity data to dictate what dosages are evaluated for FDA approval. Additionally, it is clear that a fit-for-purpose approach, where each drug development program is tailored to the drug being evaluated and population it is being designed for, will be critical to future dosage optimization efforts. Investigators are expected to discuss the usage of the novel modeling techniques and clinical trial designs outlined here with the FDA; a variety of meeting types are available for trial sponsors to initiate this, which can help to ensure that the usage of dose optimization techniques follows best practices.

While these articles highlight important principles to consider in this new era of dosage optimization, more work is needed. Particularly, many oncology therapies are now given in combination, but most dosing optimization approaches were designed with single agents in mind. Additionally, continued efforts are needed to ensure inclusion of patient input in dosing decision-making. The FDA and AACR will continue to work together with all interested parties to maintain the rapid pace of innovation and to improve the outcomes of all cancer patients.

To stay up to date on further developments, subscribe to the free monthly Cancer Policy Monitor newsletter.