From the Bench: Innovations in Cancer Vaccines

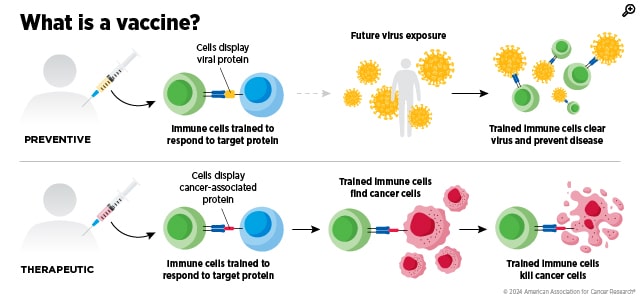

Most of us already have an everyday example of what a vaccine is. It is a kind of training exercise for your immune system: It safely shows your body a clue—often a harmless piece or imitation of a pathogen, such as a flu virus, for example—so your immune cells learn what to look for and can respond faster and stronger the next time they encounter the real threat.

A cancer vaccine uses that same basic idea, but, with few exceptions like HPV vaccines, the target isn’t a virus or bacterium—it’s cancer. Instead of teaching the immune system to recognize an outside invader, a cancer vaccine aims to help immune cells spot the subtle molecular “flags” on tumor cells that they might otherwise ignore or miss. Most of the vaccines in today’s cancer research are therapeutic, meaning they’re given after cancer has developed to help the immune system attack tumors more effectively or keep the disease from coming back. This makes it a form of immunotherapy.

Researchers push their expertise and creativity to the limits to come up with different ways to do this, and this year’s first post in our “From the Bench” series features a few studies about innovative ways they go about this.

Tagging Tumors to “Go Viral”

In a study published in Nature, the researchers started from a basic challenge in cancer immunology: many tumors don’t naturally stand out to the immune system. They often lack the antigens—the “alarm signals” that typically activate the T cells in the immune system. Not activating the T cells, the frontline defense of the body, often results in the tumor never getting attacked, allowing it to progress and spread.

To get around this challenge, researchers in this study started off by vaccinating mice with an mRNA vaccine for a virus they knew would be recognized by the immune system—hepatitis B (HB). This is called immunological memory, meaning it primed the T cells in these mice to recognize and attack any cell that “looked” like it was infected with the HB virus.

Next, the researchers “dressed up” the tumors to look like a virus-infected cell so the immune system treats it like an urgent threat and sends in the pre-armed T cells immediately. To do this, they delivered a weakened virus that they designed to replicate mainly in tumor tissue, and “tagged” these cells as ones infected with HB virus by causing them to display specific markers, called antigens, on their surface.

This tag, called a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), is recognized by the primed T cells for about a year, and this effect lasted long enough to prevent the tumor cells from growing back in mice. When the virus was first introduced to the tumor cells, it infected 30% of the tumor tissue in three days and did not “tag” the healthy cells with HBsAg. This was what the study was aiming for, because selectively targeting tumor cells while leaving healthy tissue intact makes this a much safer treatment.

Even though the immune system was initially trained to attack the HBsAg viral tag, once tagged tumor cells were killed, the cleanup process exposed the immune system to other tumor molecules. The immune system, specifically dendritic cells, could then pick up pieces of the destroyed cancer cells and present additional, naturally occurring tumor antigens to T cells. This process, called epitope spreading, means the immune systems of the mice were catching on, potentially helping the body recognize and attack tumor cells that weren’t successfully tagged or that differed from one another within the same tumor.

If future studies continue to show that the tagging remains tumor-selective and that the immune response broadens beyond the initial tag, this kind of approach could become a flexible add-on—a way to give many different cancer vaccines a strong starting target that the immune system already knows how to attack.

A “Universal Booster” Vaccine for Adoptive T-Cell Therapy

A study from Cancer Immunology Research tackles a different problem: Sometimes the T cells we need already exist—researchers can engineer them to recognize and kill cancer—but they don’t always multiply enough in the body, or they fade out before the job is done. That’s a major limitation of adoptive T‑cell therapy, where clinicians collect a patient’s T cells, grow or engineer them in the lab, and then infuse them back in. The most straightforward way to rectify this is to “boost” those infused cells with a vaccine, much like a booster shot reminds the immune system what to attack. In practice, however, this approach usually requires knowing the exact tumor target (the specific molecular fragment, or “tag”) that the infused T cells recognize—information that can vary from person to person and can be hard to turn into a scalable vaccine.

The workaround that this study showcased was to build a “universal” booster that doesn’t depend on the tumor’s unique targets, and thus could be used to treat anyone. They did this by giving the engineered T cells a second add‑on recognition system called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). The CAR was engineered by the researchers to recognize a separate, “surrogate” boosting antigen that they could supply on demand, whenever they needed the T cells to multiply. The engineered T cells still had their original tumor-recognizing machinery intact, but when it was time to expand those cells in the body, the researchers delivered a vaccine that carries the boosting antigen or the tag that the CAR would recognize, driving those cells to increase their numbers.

When tested in mice, since the CAR on the T cells could recognize this tag, it caused the cells to expand and grow, slowing tumor growth. The researchers, however, encountered one setback—this “boost” was short-lived, and so the tumors returned.

When the researchers conducted further investigations to understand why this was the case, they found that the viral vaccine itself triggers the body’s innate antiviral defenses, which can unintentionally limit how well the boosting antigen is produced and presented. When the researchers briefly blocked the protein that regulated this signaling process, boosting antigen levels increased, the engineered T cells expanded more, and tumor control improved.

Nanoparticle Fat Bubbles for Vaccine Delivery

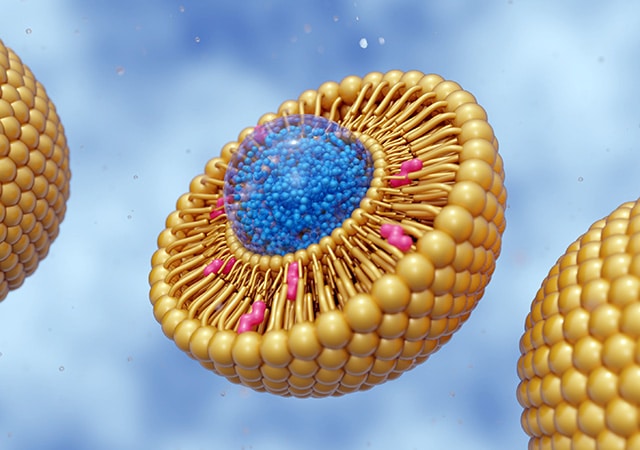

A key early step in any vaccine response is getting dendritic cells—immune cells that act like teachers—to notice the “alarm signals” or antigens and use them to train T cells to respond. As discussed in the previous section, tumors often go undercover by not triggering that kind of alarm to avoid the immune cells noticing them. So instead of tweaking the antigen or the T cells, researchers in this study in Cell Reports Medicine tried to upgrade the “danger signal” that dendritic cells create.

To do this, they built lipid nanoparticles—tiny spheres or bubbles made from fat molecules—that carry multiple immune-stimulating ingredients together. The nanoparticles were loaded with two strong innate immune activators—one that turns on the STING pathway and one that activates TLR4—and then paired with cancer antigens. Activating these two pathways at the same time pings the dendritic cells with a coordinated, high-priority “be on the lookout” message while they’re picking up the tumor antigens, which can make the T-cell training step much more effective.

By packaging these immune activator molecules and antigens together, the researchers ensured that the dendritic cell that picks up the antigen also receives the “danger” signals at the same time. In addition to having this unique construction, these fat-based nanospheres were also designed to drain into lymph nodes, where T-cell training normally happens, so that they could reach their target destination with ease.

The researchers tested this approach on mice using melanoma peptides—short lab-made sections of protein that come from molecules commonly found in melanoma cells—as antigens in this nanoparticle vaccine. Of the mice that got the nanoparticle vaccine, 80% were tumor‑free at the end of the study, which ran for 250 days. Mice in the comparison groups, unvaccinated mice and mice given more traditional vaccine formulations, developed tumors and none survived beyond 35 days.

The mice in the vaccinated group also showed protection in experiments designed to mimic cancer spreading, with no lung metastases in settings where untreated animals typically developed them.

By replacing the melanoma peptides with tumor lysate—a blended mix of proteins taken from destroyed tumor cells—the researchers could test whether the same lipid nanoparticle idea would work when the targets to vaccinate against weren’t known. This is a more real-world scenario, because while determining the specific antigen you need to cause the proper T-cell response is hard to come by, getting tumor lysate is relatively straightforward. In this setup, the vaccine still generated strong immune responses and protected mice across multiple aggressive cancers, including pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer.

This vaccine platform that enables the “two-in-one” packaging is based on how molecules dissolve in different environments. One of the agonists is hydrophilic (dissolves in polar solvents like water) and the other is hydrophobic (dissolves in nonpolar, oily solvents). The nanoparticle is designed to be able to encapsulate both of these, and this shared delivery approach produced a stronger type I interferon response, an immune signaling program that helps dendritic cells become better at activating T cells. The researchers investigated the biology around the stronger signaling and found that it was tied to increased activity in genes involved in processing and presenting antigens—the vaccine was improving the steps that help dendritic cells “show” T cells what to attack. They even saw similar signaling behavior in human dendritic cells in lab experiments of cultured cancer cells.

Another thing that the study found was that there was a “goldilocks region” of dosage when it came to this cancer vaccine. Using too much or too little of a dose would show suboptimal results. At higher doses, the researchers saw hints that the immune system may start to hit the brakes when it’s pushed too hard—almost like an internal dampener that prevents the alarm system from staying fully turned on.

The Hitchhiking Cancer Vaccine

In this study from Nature Medicine, a vaccine called ELI‑002 2P is designed to overcome a delivery problem that often limits cancer vaccines: getting enough of the vaccine to the lymph nodes, where immune responses are trained. To overcome this, the researchers added a fat-like molecule to the vaccine components, so that the vaccine could latch onto albumin, a common protein in the blood. That albumin acts like a shuttle that lets the vaccine “hitchhike” to nearby lymph nodes, helping the vaccine concentrate where dendritic cells are. The dendritic cells can then pick it up and activate cancer-fighting T cells.

The vaccine has two targets—G12D and G12R mutant KRAS proteins, because they are shared across many tumors, especially in pancreatic and colorectal cancers. It also carries short DNA fragments that can activate the TLR9 protein, an internal “danger sensor” in certain immune cells that recognizes DNA patterns that are more common in microbes than in human DNA, and puts dendritic cells into a more activated state, making them better at training T cells.

The “fat-like molecule” add-on is doing more than just giving the vaccine a ride—it’s changing the chemistry of the vaccine in a way that makes lymph-node delivery much more likely. In earlier work published in Cancer Immunology Research on this amphiphile approach, researchers investigated the chemistry behind attaching peptide antigens to a lipid chain so that it would be more likely to hitchhike its way into the lymphatic system via the albumin protein. By varying the exact linkage chemistry, it was possible to even add more than one albumin-binding “handle,” so it could grab onto the albumin protein more effectively. Their work showed that doing so would further increase lymph node accumulation and T-cell priming.

In addition to enabling this hitchhiking process, the modification also helps the vaccine stay intact long enough for that delivery route to matter. Peptide antigens are fragments of proteins, and on their own, can be fragile in the body, getting broken down quickly by enzymes. The amphiphile linkage increased peptide stability in serum and extended how long antigen presentation persisted in mice. Amphiphile-linked peptides were able to not just reach the nearest draining lymph node, they also traffic to more distant nodes, and antigen presentation could still be detected for at least a week, whereas peptides by themselves faded much faster.

In a clinical trial, 84% of the patients who received this vaccine developed mutant KRAS-specific T-cell responses, showing that the vaccine triggered the dendritic cells in the expected way. In median follow-up time of 19.7 months, people who generated stronger KRAS‑specific T‑cell responses were shown to have longer times before relapse and improved survival.

Cancer vaccines rely on a lot of innovative thinking. Tumors aren’t obvious intruders, the best targets aren’t always known in advance, and vaccine ingredients can be too fragile or too diluted to reliably reach the immune system’s training centers. The platforms and approaches here are but a few of the many that are labored on at the bench, to be the building blocks that drive the engine of cancer research forward.

To help foster the next breakthroughs in cancer vaccine research, the AACR recently partnered with the Cancer Vaccine Coalition (CVC) on the AACR-CVC Cancer Vaccine Think Tank—Transforming Cancer Care: A Global Think Tank to Accelerate Advances in Cancer Immunity. During the two-day event, renowned researchers and patient advocates discussed practical solutions to accelerate cancer vaccine development and delivery. Experts in this space will also discuss ways to advance cancer vaccines at the upcoming AACR Immuno-Oncology Conference (AACR IO), to be held February 18-21. Registration is still open for AACR IO in-person attendance and on-demand access.