Making an Impact on Rare Tumors

By Richard Lobb

AACR Communications

In the numbers game of cancer, the big players In the United States are the ones like breast cancer or prostate cancer, with hundreds of thousands of cases and tens of thousands of deaths per year.

A rare tumor, on the other hand, is one that affects 40,000 people a year, tops. Hundreds of different types of rare tumors affect only a few thousand or even a few hundred people each. But for each of those patients, their cancer is the most important one in the world. And multitudes of different rare cancers add up to big numbers.

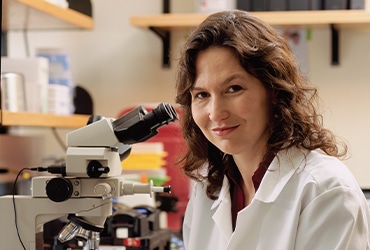

“One of the problems of rare tumors is that, even though they are individually rare in the population, collectively they make up a huge burden of cancer in the country, so they account for 25 percent of cancer mortalities,” says Karlyne Reilly, PhD, the director of the Rare Tumors Initiative at the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Cancer Research.

When Reilly was a postdoctoral researcher in the MIT laboratory of the renowned Tyler Jacks, PhD, she set about to study a rare tumor and looked for funding. She found it in the AACR-Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research Fellowship in Basic Research in 2000. The grant supported her work screening mouse models for genes associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), work that helped her win a position at NCI.

There she focused on genetic aspects of nervous system cancers, including astrocytoma and glioblastoma, spinal astrocytoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. She helped launch NCI’s Rare Tumors Initiative to help improve communication and information exchange between basic researchers and clinical researchers at NCI. She was named head of the program in 2016.

“It is difficult, sometimes,” Reilly says, “for the basic researchers to really understand the limitations that the clinical researchers face when they try and translate the ideas to the patients, and it’s hard for the clinical researchers, sometimes, to understand how the basic research could apply to the problems that they’re trying to solve. So my job has been to try and facilitate that communication, to try and understand when something might be relevant, to try and connect people together and get them networking.”

But difficulties abound. Because any particular rare tumor has relatively few patients, there’s little incentive for the pharmaceutical industry to develop specific therapies. Even if there is interest, it’s challenging to fill a clinical trial, Reilly says, and in pediatric cancers, the patients age out before trials can be completed. Some of the landmark studies in rare pediatric tumors have had to stretch over many years. Some trials have to be abandoned for lack of enrollment.

“So there may be something that works for these patients, but we can’t even get to the point of testing it,” she notes. Without data on safety and efficacy, there’s often little hope of developing a specific therapy.

Yet the benefits can be considerable, she says.

“I think a huge point to be made is how important the study of rare tumors has been to our understanding of the basics of cancer,” Reilly says. “If you look at the classical hallmarks of cancer, you can point to a rare disease that was the starting point for almost all of these hallmarks. I think it’s important to think about studying rare cancer as an inroad into studying the biology of cancer.”

The NCI rare tumors program addresses some of the challenges by utilizing its resources broadly, she says.

“One of the things we’ve done here is develop a rare tumor developmental therapeutics clinic, which is a partnership between the pediatric oncology branch and the developmental therapeutics program here,” Reilly explains. “The idea is that we can enroll across an age spectrum, and it doesn’t matter when they cross over at 18 from being a pediatric case to an adult case. We don’t want to further divide up our populations for clinical trials because of some arbitrary age cutoff.”

Reilly also worked with Brigitte C. Widemann, MD, a senior investigator and Chief of the Pediatric Oncology Branch of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, to set up My Pediatric and Adult Rare Tumor Network (MyPART), funded by the original Cancer Moonshot. MyPART involves scientists, patients, family members, advocates, and healthcare providers in the search for treatments for rare cancers.

“It’s called MyPART not only for the acronym but also for the idea that every single person has an important perspective and a role to play,” Reilly says. “Patients are experts in their own cancers, their families are often experts, the advocates are experts. We really want to take advantage of that and make everyone feel like they’re part of the enterprise.”

Reilly says her organizational skills were honed by the process of applying for the AACR grant that helped launch her career. The experience of developing a proposal and networking to obtain support and letters of recommendation was invaluable, she says. So was the confidence that came from bagging the grant and knowing that peer reviewers had found her project worthy of support, and the leadership experience involved in managing a team created as a result of the grant.

“The training you get from actually writing these grants and competing for them as a postdoc is extremely important,” she says. “All of that goes into a skill set that’s very important once you become an independent investigator.”

“AACR has been a hugely impactful organization throughout my career in terms of not only supporting young scientists, but bringing scientists together in general,” Reilly adds. “I would recommend that people involved in science think about staying involved with not only AACR but many of the organizations that are set up to help us move things forward.”