From Dry January to Sober October: Cutting Back on Alcohol

If you toasted 2023 with champagne, then woke up pledging a month of sobriety, you’re not alone.

In the past decade, movements like Dry January and Sober October have gained traction. According to a survey by market research firm Morning Consult, Dry January participation peaked in 2022, when many people decided to cut back following a rising trend of alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. This year, about 15 percent of U.S. adults said they would observe Dry January, down from 19 percent in 2022. Millennials were most likely to participate, with 19 percent of respondents saying they would abstain, followed by Gen Xers (14 percent) and Baby Boomers (12 percent).

Dry January hashtags are abundant on Instagram and Twitter, with messages ranging from snarky to serious. Motivations for observing Dry January include curbing addictive behavior, seeking better sleep, cutting calories, and for some, taking steps to prevent cancer.

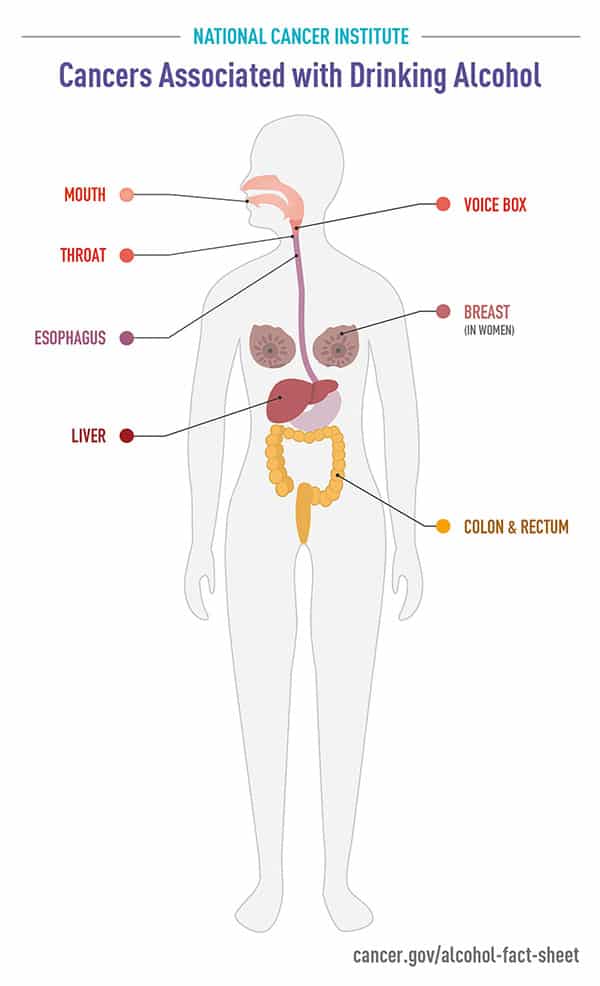

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has linked alcohol to increased cancer risk. An International Agency for Research on Cancer study published in August 2021 in The Lancet Oncology found that globally, more than 741,000 cases of cancer, or about 4.1 percent of all cases diagnosed in 2020, were attributable to alcohol. Esophageal, mouth, throat, larynx, breast, colorectal, and liver cancer have all been tied to drinking.

In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) listed alcohol as the third leading modifiable risk factor for cancer, after tobacco use and excess weight, and issued a clear recommendation: “It is best not to drink alcohol.” For those who do drink, ACS recommended that men drink no more than two drinks per day, and women no more than one per day.

Health experts acknowledge that getting Americans to abstain is a tough challenge. According to the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 69.5 percent of Americans age 18 and over reported drinking within the past year, and 54.9 percent reported drinking within the past month. More than a quarter reported binge drinking (consuming five or more alcoholic beverages for men; four or more for women) in the month before the survey.

Alcohol and Cancer Risk: What You Don’t Know Could Hurt You

Decades of advertising and positive news coverage have left many Americans believing that alcohol has health benefits. Changing this belief is an important public health goal that could require mass media campaigns, tailored interventions, and warning labels, stated authors of a study and commentary published in December in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“All types of alcoholic beverages, including wine, increase cancer risk,” said senior author William M.P. Klein, PhD, associate director of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Behavioral Research Program. To assess Americans’ awareness of this risk, he and colleague Andrew Seidenberg, MPH, PhD, conducted an analysis of the 2020 Health Information National Trends Survey 5 Cycle 4 and discovered that only 20.3 percent were aware that wine was linked to cancer, compared with 24.9 percent for beer and 31.2 percent for liquor.

What’s more, 10 percent of U.S. adults said wine decreases cancer risk, while 2.2 percent said beer decreases risk and 1.7 percent said liquor decreases risk.

This analysis confirmed that wine, in particular, has developed a “health halo,” wrote Jennifer L. Hay, PhD, a psychologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in a commentary accompanying the study. She traced positive public opinion about wine to a 1991 “60 Minutes” story on the French Paradox, which questioned why the French population had low rates of heart disease despite high consumption of fatty foods. At that time, some suggested that red wine conferred health benefits—a theory that was never fully proven, yet has persisted for decades.

“This ‘health halo’ surrounding alcohol consumption leads the public to overgeneralize alcohol health benefits to other diseases, including cancer,” Hay and colleagues wrote.

In the NCI study, Klein noted that “in the prevailing context of national dialogue about the purported heart health benefits of wine,” significant effort will be necessary to inform Americans of the risks associated with drinking.

“Educating the public about how alcohol increases cancer risk will not only empower consumers to make more informed decisions, but may also prevent and reduce excessive alcohol use, as well as cancer morbidity and mortality,” he said.

Hay and colleagues agreed, noting that even modest behavior modifications could benefit many people.

“Even with full information regarding the cancer harms of drinking, many will certainly continue to imbibe. Nevertheless, increased awareness could result in people making more informed decisions about their alcohol consumption. For example, lighter drinkers might avoid increasing their consumption, former drinkers might avoid resuming, and heavier drinkers might use evidence-based interventions to reduce their consumption. Families with stronger cancer histories may also use this information in important ways to manage their family cancer risks. In all cases, and for all members of the public regardless of the magnitude of their alcohol consumption, informed decision making about drinking cannot happen without full awareness of the health harms of alcohol,” the commentary authors wrote.

The new articles underscore findings of a 2020 National Cancer Institute workshop and webinar titled Alcohol as a Target for Cancer Prevention and Control: Research Challenges. Co-chair Susan Gapstur, PhD, MPH, discussed the need for improved communication about the dangers of alcohol in a paper in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. And in an interview with Cancer Research Catalyst last year, she acknowledged that most people are unlikely to abstain completely.

“I think we need to be smart about our consumption.” Gapstur said. “Having a glass of wine or other alcoholic beverage occasionally is unlikely to be harmful. But we need to be aware and understand the risks of consumption, and when you’re balancing those risks, you should be mindful of the full body of evidence of the health effects of drinking.”