Experts Forecast 2024, Part 1: Advances in Cancer Vaccines

2024 is here, and there is so much on the year’s agenda—a total solar eclipse over parts of North America; the Summer Olympics in Paris; the first crewed lunar mission in over 50 years; and major elections around the world, including the presidential election here in the United States.

Good thing we have an extra day this year to get through it all!

As we leap into 2024, what lies ahead for cancer research?

We asked four thought leaders to answer this question for each of their respective fields. Across the board, there was significant optimism about the progress ahead in 2024. This optimism follows a busy year in the cancer research realm: 2023 featured 45 oncology approvals by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including for 17 new drugs; the unveiling of the National Cancer Plan; and a new director for the National Cancer Institute, W. Kimryn Rathmell, MD, PhD.

In this four-part series, we’ll summarize what experts forecast for 2024, beginning with predictions from Catherine J. Wu, MD, FAACR, for the field of cancer vaccines.

Stay tuned for parts 2-4, featuring thoughts from:

- Robert A. Winn, MD, FAACR, on achieving health equity;

- Paul Workman, FMedSci, on using AI and other cutting-edge technologies for oncology drug discovery; and

- AACR President-Elect Patricia M. LoRusso, DO, PhD (hc), FAACR, on precision medicine and biomarker-driven clinical trials.

Broadening the reach of cancer vaccines in 2024

For decades, researchers have tried—with some success—to develop vaccines to treat cancer.

The idea is simple: inject patients with a biologic that stimulates their immune systems to attack the cancer. The execution? Not so easy.

Time-consuming research, costly manufacturing, and unknowns about the appropriate stimuli are some of the challenges researchers have faced. But recent advances—spurred, in part, by the success of mRNA vaccines to protect against COVID—have allowed researchers to make headway.

This year, we can expect even more progress, according to Catherine J. Wu, MD, FAACR, the Lavine Family Chair of Preventative Cancer Therapies at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

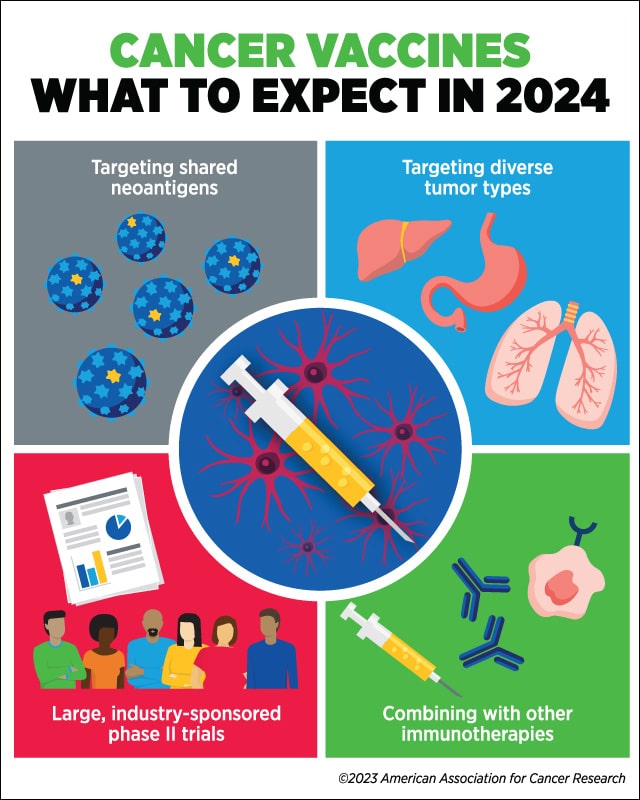

Wu predicts that 2024 will bring developments in targeting shared neoantigens, treating diverse tumor types, combining vaccines with other immunotherapies, and evaluating cancer vaccines in large, industry-sponsored phase II clinical trials.

“I expect to see renewed interest in targeting shared neoantigens that arise from driver mutations in different tumor types, which could allow us to make progress in creating off-the-shelf vaccines,” she said.

While personalized vaccines—which target patient-specific neoantigens that arise primarily from passenger mutations—account for addressing the tumor heterogeneity present among patients, they are costly, both in terms of time and money. “It takes quite a bit of effort to generate the sequencing data to evaluate each patient’s unique cancer and then design a vaccine in real time based on the data,” she explained. “On top of that, you have the cost of manufacturing a tailored vaccine.”

Vaccines targeting shared neoantigens, on the other hand, could be readily available and deployed to a greater number of patients. However, Wu cautioned that a challenge for these vaccines is the differences in the patient genes that control responses to antigens, known as HLA alleles. “Most off-the-shelf products are geared towards epitopes that are presented in the context of the common HLA alleles, and hence may not be applicable to large populations of patients. We must acknowledge that HLA [alleles] are the most diverse loci of our genome,” she noted.

Wu anticipates that vaccines, whether they target shared or personalized neoantigens, will be studied in several different cancer types and disease settings in the coming year. “I think we’re going to see more studies that will consider how to incorporate vaccines into the standard of care or other modalities of cancer immunotherapy for whichever cancer type is under study.

“Another major development over the next year that we may see is larger-scale studies,” she added. Wu explained that, to date, most trials evaluating personalized vaccines have been small phase I studies with approximately 10-15 patients and have been conducted at academic centers. “In the next year or two, I expect that we will see more and more phase II trials sponsored by industry, where there are more resources to conduct larger trials,” she said.

Wu and others have suggested that vaccines may make immunologically inert tumors (the so-called ‘cold’ tumors) more vulnerable to other forms of immunotherapy. This year, she expects that researchers will continue to evaluate vaccines in combination with different immunotherapies.

“Vaccines, in many cases, are more effective when given as a one-two punch together with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” she said. “The fact that immune checkpoint inhibitors are approved to treat multiple cancers makes it possible to envision such combinations.”

She noted that there is also a strong rationale to combine vaccines with CAR T-cell therapy and other cell-based immunotherapies. “I think in the next period to come, we’re going to see interesting combinations—whether dual, triple, or more—that address the immune-evasive and immune-suppressive mechanisms that we have to contend with when addressing cancers.”