Melanoma Awareness Month: Improving Treatment for an Aggressive Skin Cancer

The days are getting longer and warmer, and visions of beach trips, cookouts, and picnics occupy our minds. While this year’s summer will likely look different due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, months of staying inside may make the desire to head outdoors even stronger.

As we approach the end of Melanoma Awareness Month and head into the summer, it will be just as critical as ever to understand the risk factors for melanoma and to remember the importance of proper sun protection.

What is melanoma?

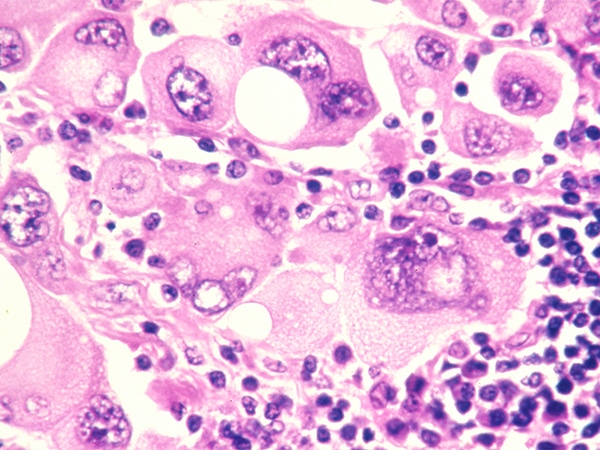

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that originates in melanocytes, which are the cells that provide color to the skin. While melanoma is rarer than other forms of skin cancer, it is more aggressive and more likely to spread to other organs. It is also associated with a higher mortality rate.

Melanoma can affect anyone, but the disease is most common in white individuals and in individuals who are between 65 and 74 years of age.

It is estimated that over 100,000 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in the United States in 2020 and that 6,850 people will die of the disease. While the mortality rate from melanoma has decreased dramatically over the past few years, the incidence of the disease appears to be rising.

How can the risk of melanoma be reduced?

One of the major risk factors for melanoma is exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays, as these can lead to cancer-causing mutations in the DNA of melanocytes. The main source of UV rays is the sun, and other sources include tanning beds and sun lamps. To protect the skin and eyes from UV rays, experts recommend applying sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher) before going outside and reapplying periodically; avoiding long stretches of sun exposure; wearing long sleeves, hats, and sunglasses when outside; and avoiding sunbathing and indoor tanning. Ongoing research aims to determine the effectiveness of these methods in preventing melanoma.

In addition to UV ray exposure, other risk factors include having fair skin that freckles or burns easily, having several or large moles, having a history of blistering sunburns, and having a family history of unusual moles or melanoma.

What are the latest advances in treating melanoma?

Advances in melanoma treatment over the past two decades have led to a steep decline in mortality. Ongoing research continues to build on these advances.

Promoting antitumor immune responses in ‘cold’ melanomas

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibition has become an increasingly common treatment for melanoma. This therapy works by releasing the brakes on the immune system, thereby allowing it to mount a response against the tumor. Immune checkpoint inhibitors that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of melanoma are pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), and ipilimumab (Yervoy).

While these therapies lead to durable responses in some patients with melanoma, “approximately 40 percent of melanomas are considered to be ‘cold,’ meaning that they lack sufficient infiltration of immune cells within the tumor and therefore have poor responses to this therapy,” said Adil Daud, MD, clinical professor at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and director of melanoma clinical research at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In a study that was recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), Daud and colleagues examined the impact of treating patients with “cold” melanomas with a combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and DNA encoding IL-12 (tavokinogene telseplasmid, or TAVO). IL-12 is a protein that triggers the recruitment of immune cells.

Previous studies have found that systemic administration of IL-12 leads to several toxicities. To help reduce the risk of such toxicities, Daud and colleagues used electrical pulses to administer IL-12 directly into melanoma lesions.

The phase II trial enrolled 23 patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who were predicted to respond poorly to pembrolizumab. Out of 22 evaluable patients, eight patients had a complete response to the combination therapy, and one patient had a partial response.

Tumor regression was observed in lesions that received TAVO directly, as well as in 29.2 percent of untreated lesions. This suggests that delivering TAVO to some lesions can lead to proliferation and circulation of cancer-specific immune cells throughout the body, explained Daud. In addition, the combination treatment led to an increased number of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and increased the expression of immune-activating genes.

Grade 3 or higher adverse effects were limited and included pain, chills, sweats, and cellulitis, in addition to the toxicities typically observed with pembrolizumab alone, Daud noted.

“Combining pembrolizumab with TAVO electroporation improved responses for these patients who were predicted to have very poor responses to single-agent immune checkpoint inhibition,” said Daud.

Improving responses to BRAF and MEK inhibitors

Inhibitors of two signaling proteins, BRAF and MEK, are commonly used in the treatment of melanoma. While these inhibitors lead to responses in most patients with melanoma, the responses tend to be short-lived due to the development of resistance. The Opening Clinical Plenary Session of the AACR Virtual Annual Meeting I featured two studies that examined different strategies to improve responses to BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

The first presentation reported results from the IMspire150 clinical trial and was delivered by Grant McArthur, PhD, head of the molecular oncology laboratory and a senior consultant medical oncologist at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia. This phase III study found that patients who were treated with a combination of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf), the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib (Cotellic), and the immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) had longer progression-free survival and duration of response than patients treated with vemurafenib, cobimetinib, and placebo.

The second presentation reported results from the SWOG S1320 phase II clinical trial and was delivered by Alain Algazi, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco. This study compared the clinical efficacy of continuous vs. intermittent dosing schedules for the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and the MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist). Previous preclinical studies had found that intermittent dosing of BRAF or MEK inhibitors delayed the development of resistance in animal models, suggesting that intermittent dosing may improve clinical outcomes in patients. However, Algazi and colleagues found that patients who received intermittent dosing had significantly lower progression-free survival than those who received continuous dosing.

Detailed descriptions of these two studies can be found in a previous post on this blog.

Research and clinical trials such as these lead to a better understanding of melanoma and may ultimately contribute to improved therapies and the development of new treatments.