Trusting the Gut (Microbiome) in Diagnosing and Treating Colorectal Cancer

It really does pay to trust your gut … microbiome. That is what some researchers are discovering as they search for new ways to diagnose early-onset colorectal cancer, offer adjuvant therapy, or manage metastatic disease.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute, but while disease incidence has declined in those over 65, diagnoses of people under 55 nearly doubled from 11% in 1995 to 20% in 2019, according to a 2023 study published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. In January 2024, that same journal reported that colorectal cancer is now the leading cause of cancer death in those under 50—it was the fourth highest in the 1990s.

These rates have led to a push by the U.S. government and American Cancer Society to lower the recommended screening age from 50 to 45, but only about 20% of those between 45 and 49 opt to get tested, according to the 2023 CA study. And even if they do, younger patients tend to get diagnosed with colorectal cancers in later stages, as patients may ignore their symptoms, mistake them for hemorrhoids, or go through a lengthy diagnosis process given that doctors don’t typically consider colorectal cancer in that age group.

While doctors and researchers aren’t sure what is behind the rise of early-onset colorectal cancer, some are turning to the gut microbiome for answers. This bustling ecosystem of trillions of different bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses work together to help our intestines—and the rest of our body—perform its functions with ease. The role of the gut microbiome in overall health has been studied for years, and when it comes to colorectal cancer, researchers are looking at it to detect early signs of disease, to boost antitumor immunity, and to plug leaks following surgery.

Could Gut Bacteria Predict Early-onset Colorectal Cancer?

Each tumor type has a distinct microbiome. And a couple of recent studies dove in to find potential differences between the tumor microbiomes of younger vs. older colorectal cancer patients.

One group of researchers used the publicly available curatedMetagenomicData of 1,394 patients, including 701 with colorectal cancer and 693 in a control group, in a study published in Cancer Prevention Research. Those with colorectal cancer were broken into three age groups based on the recommended ages for screening: those under 50, 50-65, and over 65. In examining their fecal microbiome compositions, the researchers found an increase in Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides fragilis, and Methanobrevibacter smithii in patients under 50 years old with early-onset colorectal cancers.

Another group of researchers examined electronic medical records from the Cleveland Clinic between 2000 and 2020 of 136 people diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 50 and 140 people diagnosed after the age of 60, in a study published in eBIOMedicine. They then tested the surgically resected tumors of these patients. They also found Akkermansia and Bacteroides were more abundant in patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. The researchers noted that further studies should explore the possibility of using these bacteria as biomarkers to potentially diagnose and catch early-onset colorectal cancer—earlier.

Attacking Tumors With a Fasting-mimicking Diet

Past studies have found that a fasting-mimicking diet (FMD) can have potent anticancer effects, and now researchers may have a better understanding of why. As its name suggests, FMD is medically designed to achieve a fasting-like state for individuals, but in a safe way through a diet that allows for the periodic consumption of low-calorie and low-protein foods. In a study published in Cancer Research, researchers examined the use of FMD in both mouse models and human clinical trial participants with colorectal cancer to see if this diet results in the improved antitumor immunity discovered in previous FMD trials.

In the human portion of the study, 10 participants were put on an FMD and 10 on a regular diet three days before surgery. The FMD consisted of tea, broths, steamed eggs, virgin olive oil, tofu pudding, milk, and whole grain bread, with the total consumed calories declining from approximately 600 on day one to approximately 300 on days two and three. Participants were allowed to eat the allotted diet at any time of the day. Those in the control group were instructed to stick to their usual diet while maintaining their weight.

The researchers observed that those who were on an FMD had a reduced number of B cells switching to immunoglobulin A (IgA) within the local tumor microenvironment. IgA is an antibody that serves as one of the immune system’s first lines of defense on mucosal surfaces—such as those found in the digestive system—but it has also been shown to have both pro- and anti-tumor effects depending on the cancer type. In colorectal cancer, for example, high levels of IgA have been associated with poor outcomes, according to a study published in Frontiers in Immunology.

The connection between diet, the microbiome, and B-cell function in relation to the production of autoantibodies was examined in a review also published in Frontiers in Immunology. The authors found various studies linking the three, including one that observed how certain probiotic bacteria increased B cells switching to IgA.

In the FMD study, the researchers found the diet they provided boosted fatty acid oxidation in the mouse models, which induced the metabolic reprogramming of B cells to prevent them from switching to IgA. As a result, the authors note, FMD can potentially be an effective adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer by activating antitumor immunity; previous trials have found that preventing B cells from switching to IgA can boost the efficacy of cancer treatments such as chemotherapy.

Further studies, however, still need to confirm FMD’s benefit before being widely adopted in therapy.

Stopping the Leak Post Colon Surgery

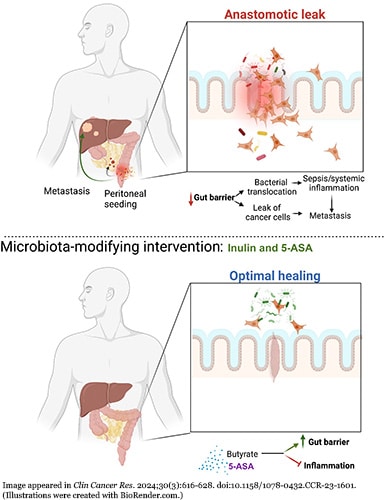

After surgical resection of a segment of the colon or rectum in patients with rectal cancer, up to 30% of patients can experience poor healing due to an anastomotic leak (AL) of intestinal content, according to a study published in JAMA Surgery. Other researchers assessed the prognosis of AL in colorectal patients, in a study published in Clinical Cancer Research. They reviewed charts from 135 patients who experienced AL at their institution, the Institut Du Cancer de Montréal, from 2011 to 2021 and compared them to the records of 360 colorectal cancer patients who had an uneventful recovery following surgery. Those with AL had both a lower recurrence-free/progression-free survival and lower overall survival.

Hypothesizing that AL may be allowing cancer cells to escape the gut and cause cancer to recur, the researchers studied plugging this leak using either a supplement or anti-inflammatory agent to reinforce the gut to test if they could turn the survival numbers around.

The researchers gave the dietary supplement inulin (a type of probiotic fiber) or 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) (an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases) to mice with colorectal cancer. After two weeks, they administered a fluorescent signal to see if it would permeate through the gut and found higher levels of the signal in the upper abdomen of the control group mice, which received neither inulin nor 5-ASA.

Additionally, the researchers performed colonic surgery on three groups of mice—one receiving inulin, one receiving 5-ASA, and the control group that received neither—and closed the wound with a suturing model associated with poor healing to observe potential leakage. Compared with mice in the control group, those that received either inulin or 5-ASA had smaller local anastomotic tumors, which the researchers associated with having a stronger gut barrier.

The authors of the study noted that these findings support targeting the microbiota with supplements or treatments to strengthen the gut barrier to reduce AL and the growth of metastatic disease after surgery, but stated that further clinical trials are needed to confirm these results in human patients.

So, trust in the gut microbiome to help diagnose and treat colorectal still needs to be earned, but things are looking promising.